“300 feet!” Bouncing off the crest of a three-foot wave, our 20 ft vessel peaked and then slapped the water causing a mist of sea spray to envelop the deck. The sea was alive, but under the bright sun it still retained a serene Caribbean blue. “200 feet!” I looked across the deck at my fellow divers perched along the gunnel. Laden with slates, meter sticks, and tapes and bouncing along with the boat, the five of us looked (and felt) ready to go. “100 feet!” The cries came from Kevin, our captain, who was navigating to our GPS point. He glanced back continuously between the oncoming sets, checking on the readiness of the team and making sure no one had fallen in prematurely. “50!” As the countdown dropped, a silence fell over the back of the boat as the team waited for the final call. This had to be a precise drop, as we were aiming for a specific GPS point in an area with currents that could take you far off target with each second spent on the surface. I settled in, secured my gear, and made sure everything was ready to go. “Go!!” came the call, and in went the divers. After a brief surface check, the team went straight down and began the next mad rush of the hour – the data collection.

My time in St. Croix was a wild, hectic dash – but it had to be. I was here in the Virgin Islands to take part in the National Coral Reef Monitoring Program (NCRMP). This program, started as a collaboration with the NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program and a large assortment of governmental/academic partners, monitors most of the coral reefs located in US waters. This amounts to a lot of surveying, covering reefs in the Pacific (Guam, American Samoa, Hawaii) to the Caribbean (Florida, Puerto Rico, US Virgin Islands). This is a colossal effort, requiring hundreds of people around the country to spend thousands of hours above and below the water. As well as frequent monitoring to collect a myriad of data on these reefs, this program also aims to standardize the methods of data collection as well as to collect data on a wide enough geographic spread to put sites into the context of the landscape – see how change at one site relates to that of their neighbors, or their distant relative. All that being said, we had a lot of work to do – with a goal of hitting 250 sites in two weeks, there was no time to waste.

As such a large program, it required lots of divers. This trip was composed primarily of four organizations: NOAA/NMFS, the NPS, University of Virgin Islands, and the Nature Conservancy. As such a large group the entire team rarely got together in one place, with the exception of an organizational meeting monday morning. This was held at a NPS building at the Christiansted National Historic Site, an old Dutch colonial settlement built on the island, in a repurposed warehouse originally built in 1749. Here I was able to meet the many members of the St. Croix NCRMP team.

- Our historic rendezvous point

- Some weaponry at Fort Christiansvaern

After the meeting, each organization was split up into 6 different vessels and sent to different ends of the island, each with a different section of coastline to survey. Within those areas, each team was given GPS coordinates for new sites daily. These sites were randomly generated to obtain unbiased data and were stratified by depth and habitat type to encompass a diversity of environments.

While there was lots of data to be taken, I was starting the week off taking photos, working to document the survey methods. I was also doing a bit of shadowing, to learn the species of these clear Caribbean waters. This was a new area to me – I’d never dove in the Caribbean (or the Atlantic for that matter) and hadn’t done any tropical diving in four years. That fact alone made this trip quite the novelty – I learned to dive and got my first few certifications in warm water, but then jumped over to cold water while in college and hadn’t come back to the warm side since – so diving in a 3mm wetsuit with no added weight was a forgotten luxury. The 80-degree water was pretty nice too. I’d spent the last couple weeks in water averaging 38 degrees and the past couple years diving in the mid 50-degree Californian waters, making the tropical water was a welcome relief. This was also some of the nicest visibility I’d seen in a while. Overall, I was heavily enjoying my re-introduction to warm water diving.

While shadowing and photographing my team, I learned the down-low of the survey methods. I’d read about them in the mission protocol document, but nothing compares to seeing them in action. This program collects data on corals, fish and benthic cover, with the primary objective of determining the health of the reef. Each survey team was comprised of four divers: a coral demographic diver, line-point intercept diver, and two fish divers. Coral and fish divers surveyed coral and fish respectively (big surprise), collecting data on species, size, and abundance to determine health and diversity. Line-point intersect (which is the role that I was going to assume after my shadowing and photographic obligations ended) was responsible for collecting percentage cover information with species, substrate, and relief data that was collected under predetermined points on the meter tape. This data is used to get an idea of the overall character and species composition of the reef.

Through my shadowing I got a close look at seasoned surveyors doing their thing in the water and was able to observe them at work. My team consisted of mainly NOAA folks: Kim Edwards, Laughlin Siceloff, Erin Cain, Michael Nemeth, as well as a diver from the Nature Conservancy, Allison Watts. Allison, as I discovered on one of my first days on the boat, is also part of the Our World Underwater family – she was the 2012 Monterey Bay Aquarium Dive Safety intern! Small world! Everyone apart from Allison and myself had had lots of experience with these protocols and species, so they were excellent resources for me to run all my questions by.

- Erin Cain writing down fish survey data

- Laughlin Siceloff searching for some of the more cryptic benthic residents of the reef during a fish survey

Each day was action-packed with diving: we’d start off by boating out towards our first assigned site of the day, do a quick drop, descend on our site, collect the data, and head back up for another one. Each team was given five sites to handle a day, which was relatively achievable given the survey protocol. Dives averaged between 30-45 minutes, so this ended up being only around 3 hours in water a day. And with this type of repetitive, back-to-back diving, time really flies. Each day went by in no time at all, with the only real surface interval we needed being the transit between sites (thanks nitrox). That time was occupied as well, as the team switched tanks and data sheets, as well as the obligatory disinfecting of survey gear. One of the big things that this program is looking for is coral disease, which is hypothesized to potentially be able to spread via divers. This resulted in a thorough gear disinfectant protocol, with everything requiring a sterilizing soak between dives and at the end of the day.

After spending the first couple days photographing the team at work and the sites, I moved on to data collection. At first, I was just collecting mock data, allowing me to get hands-on experience and later compare my work to others to see how I did. With such a rigorous dive schedule, I got plenty of practice. While I was initially scheduled to continue doing these mock surveys for a while longer, an unexpected turn of events left us a team member down and I was thrown into the mix – it was time to prove myself. Thankfully, my practice had paid off (and the sites weren’t incredibly diverse, allowing me for an easy intro to the line point intersects) and I was able to complete all my work and not hold the team up for too long.

- Michael Nemeth powers through a coral survey

- Coral demographic divers collect data on coral seen on transect, including collecting size measurements – a pre-marked meter stick helps with sizing on the go

- Hard at work – Erin Cain and Michael Nemeth work away on their benthic survey

- Kim Edwards works on a coral demographic survey, using her meter tape to mark area already covered, while Allison Watts collects line point intersect data

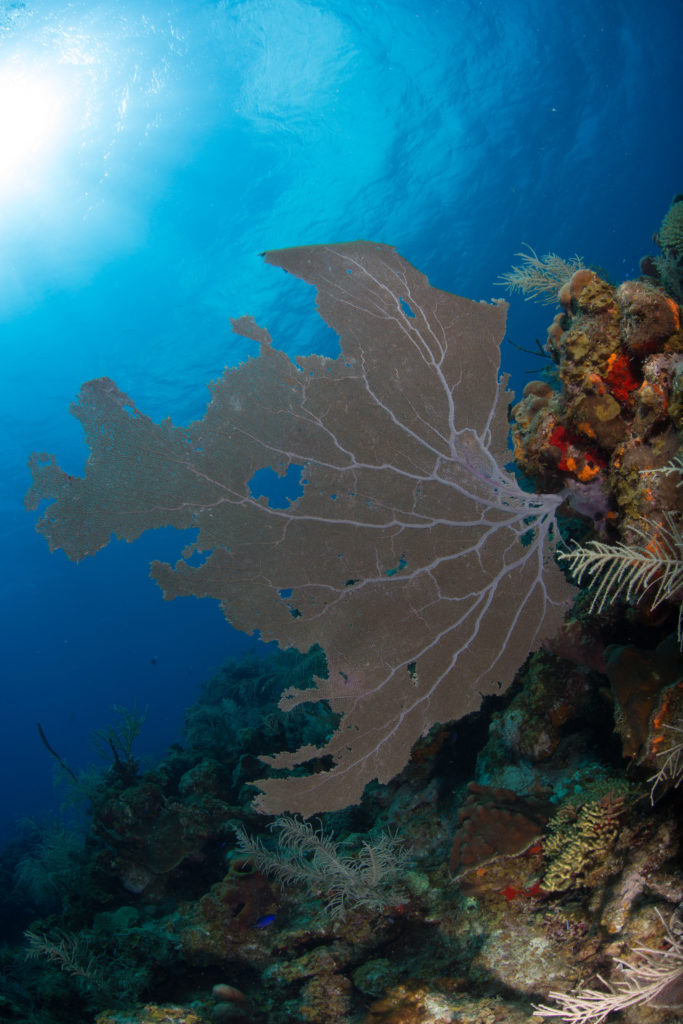

As someone who’d never dove these waters and hadn’t been on coral reefs in years, I thought the marine life was pretty incredible. The sea floor on most sites was covered in gorgonians and basket sponges, with assorted fish traveling through them. I saw lots of nurse sharks, garden eels, big rays, barracudas, octopuses. On one memorable dive we descended through a layer of gelatinous zooplankton so thick that you couldn’t see through them – it looked as though you were dropping into a bottomless ocean until you’d cleared the cloud of ctenophores, cydippids, and salps. While not every site was beautiful (randomly selected survey points works like that sometimes), that made the nice ones even more special. We ended up on some nice patch reefs, ones with enough coral to put the team to work. We also had the pleasure of diving with a curious group of dolphins on one of our surveys – which, let me tell you, is not distracting at all. They even stuck around for our safety stop, where I was able to watch one breach from underwater. It was incredibly elegant to see and looked like it effortlessly left the water.

Despite my wonder at all these new species, I couldn’t ignore the fact that these reefs weren’t healthy. As the LPI diver, it was jarringly obvious to me how much macroalgae I had on my transect. It was also very clear to me that the substrate that this macroalgae was on most of the time was coral skeleton. Bleaching and disease have ravaged these reefs, making life as a coral colony very difficult. I was an inexperienced disease-spotter, but I listened to my team talk about it on almost every surface interval. Thankfully, it wasn’t too prevalent on our sites, although it was there. The death of the coral colonies creates available substrate that is quickly colonized by opportunistic macroalgae, creating a bland monochrome landscape where vibrance used to thrive.

This pillar coral (Dendrogyra cylindrus) is dead on its lower half, where macroalgal species have already established themselves

While this particular reef has some nice patches of coral, it’s easy to see the numerous clumps of macroalgae covering all the area in-between.

If bleaching and coral disease weren’t enough, these reefs are also subject to intense hurricanes. Recently devastated by Hurricane Maria in 2017, the subtidal systems here are still recovering. St. Croix gets hit or brushed by hurricanes every 3 years or so on average, with hits by serious storms every 18 years. Tropical storms like these create a cooling effect that can be beneficial for coral reef ecosystems, as it relieves them of potential heat stress, but they can also be heavily damaging. Strong storm-induced waves can destroy coral colonies, especially the more delicate branching forms (like Acropora spp.). These storms can also flush anthropogenic nutrients into the nearshore environments, creating fuel for fast-growing algal species who can compete with coral larvae for space. The violent effects of these storms were bluntly presented to me when we conducted surveys on sites in an area known as the ‘Haystacks’. The haystacks are huge piles of skeletons of Acropora palmata, or elkhorn coral, all broken up by years of hurricanes. These piles are massive – easily 25-30 feet wide and up to 20 feet tall – and are almost completely devoid of coral growth. Typically, when Acropora corals are broken up from storms, the fragments can reestablish and continue growth, but that wasn’t the case here. Standing tall, dead and covered in algae, the haystacks were a poignant image of the unfortunate state of coral reefs to me. What at one point was a literal wonder of the natural world, a gigantic branching maze of living creature, now lies dead in a huge pile – a mass grave of coral.

- The haystacks – photos don’t really do the site justice. Photo by Erin Cain

- These piles were massive. This one is probably 20-25 feet tall. Photo by Kim Edwards

My week in St. Croix went by fast – the daily schedule jam-packed with diving made the week fly by, causing Friday to feel like it came mere hours after Monday evening. While exhausting, this repetitive survey diving is something I love dearly. I started diving doing biological surveys on coral reefs and gained most of my dive experience conducting monitoring dives in California’s kelp forests, so jumping back into survey diving and swimming up and down a transect tape felt like a welcome home. As a marine biologist by training and an avid marine conservationist, the value of marine monitoring programs isn’t lost on me. I’m grateful that I’m able to take part in such a large-scale program such as NCRMP, especially when considering the state of coral reefs today. Work like this couldn’t be more important, as these monitoring programs allow for widespread dissemination of invaluable data on ecosystem condition and health, hopefully up to the governing bodies that have the power to make the huge changes necessary to save these struggling seas.