It’s like stepping outside into hot orange juice. The Florida humidity is thick and muggy. I’ve spent time in humid places before but for some reason, I feel like I’m going to melt here.

I’m in Florida to join the South Florida Caribbean Network (SFCN) dive team; A group of NPS scientists who inventory and monitor natural resources in Biscayne, Dry Tortugas, and the US Virgin Islands.

Dr. Mike Feeley of the SFCN has invited me out on their 10-day trip to the Dry Tortugas National Park (DRTO) to conduct lobster surveys. The SFCN has long-term data on coral reefs, seagrasses, and fishes in the Florida and Caribbean parks, but these lobster surveys are a new addition to their dataset, and this is the first year they are surveying in the Dry Tortugas.

The Caribbean spiny lobster (Panulirus argus) is one of the most economically important fisheries in Florida. Dry Tortugas has been a no-take zone for lobster since 1974, today the lobster is under substantial recreational and commercial fishing pressure, including within park boundaries further north in the Keys at Biscayne National Park. The SFCN is hoping to gather data on population density, size, and biological condition of adult Caribbean spiny lobsters. The data collected by the SFCN will then be used to inform park managers of the status of spiny lobsters within their park boundaries and evaluate any potential management actions.

My first day in Florida and immediately I connect with the SFCN crew in Miami, catching a ride with Mike Feeley and Lee Richter as they trailer the 27-foot power cat, Twin Vee, down the Keys. Rob Waara and the two SFCN University of Miami interns Allison Kreyer and Davis Richmond are provisioning for our journey, and we will all meet up in Key West.

It is my first time in the Keys. Atlantic Ocean on one side and Florida Bay and Gulf of Mexico on the other. I notice the painted fish murals, oversized marine creature sculptures, and abundance of anything fishing related. We make a stop at Denny’s café and I get to experience my first real Cubano and café con leche. We then drive the 7-mile bridge and I keep an eye out for the mini deer that inhabit Big Pine Key.

There are thousands of lobster pots lining the road on the way down. Lee explains how they have a “mini-season” where for two days at the end of July before the commercial and recreational fishery opens, the Keys are overrun with upwards of 50,000 people looking to catch lobster. This blows my mind. How could this ever be sustainable? Lee describes how the Keys are situated at this perfect location for lobster recruitment. Larval lobster get sucked up from the rest of the Caribbean by the Gulf Stream and settle in the good juvenile habitat in Florida Bay which is protected from lobstering. Then, as they get older, they migrate out to the deeper reefs. This is one reason why it will be interesting to compare data from Biscayne (legal to lobster in some parts) and Dry Tortugas (illegal to lobster). 5 hours later we arrive in Key West with its pastel-hued wooden Victorian/Caribbean-style houses.

The crew is staying at the Naval base at Trumbo Point where the park boat M/V Fort Jefferson is docked. I had planned to stay with them, but my US passport isn’t acceptable identification and I’m not allowed on base. Mike helps me find a decently priced place in Key West right off Duvall St. A bit of a hassle but the free happy hour wine at the hotel makes up for it. We go out for pizza dinner as a crew. The next morning after another few hours of trouble, Mike manages to get me on base, and once onboard the Fort Jefferson, we shove off, heading 70 miles west out into the Gulf to the Dry Tortugas National Park. Fort Jefferson is a 110-foot park boat used to transport staff and supplies between Dry Tortugas and Key West. It will be our home for this trip, the mothership. We are towing the 27′ Twin Vee behind, she will be the runabout during the dive days. Brian Lariviere is the one-man captain and crew on this voyage.

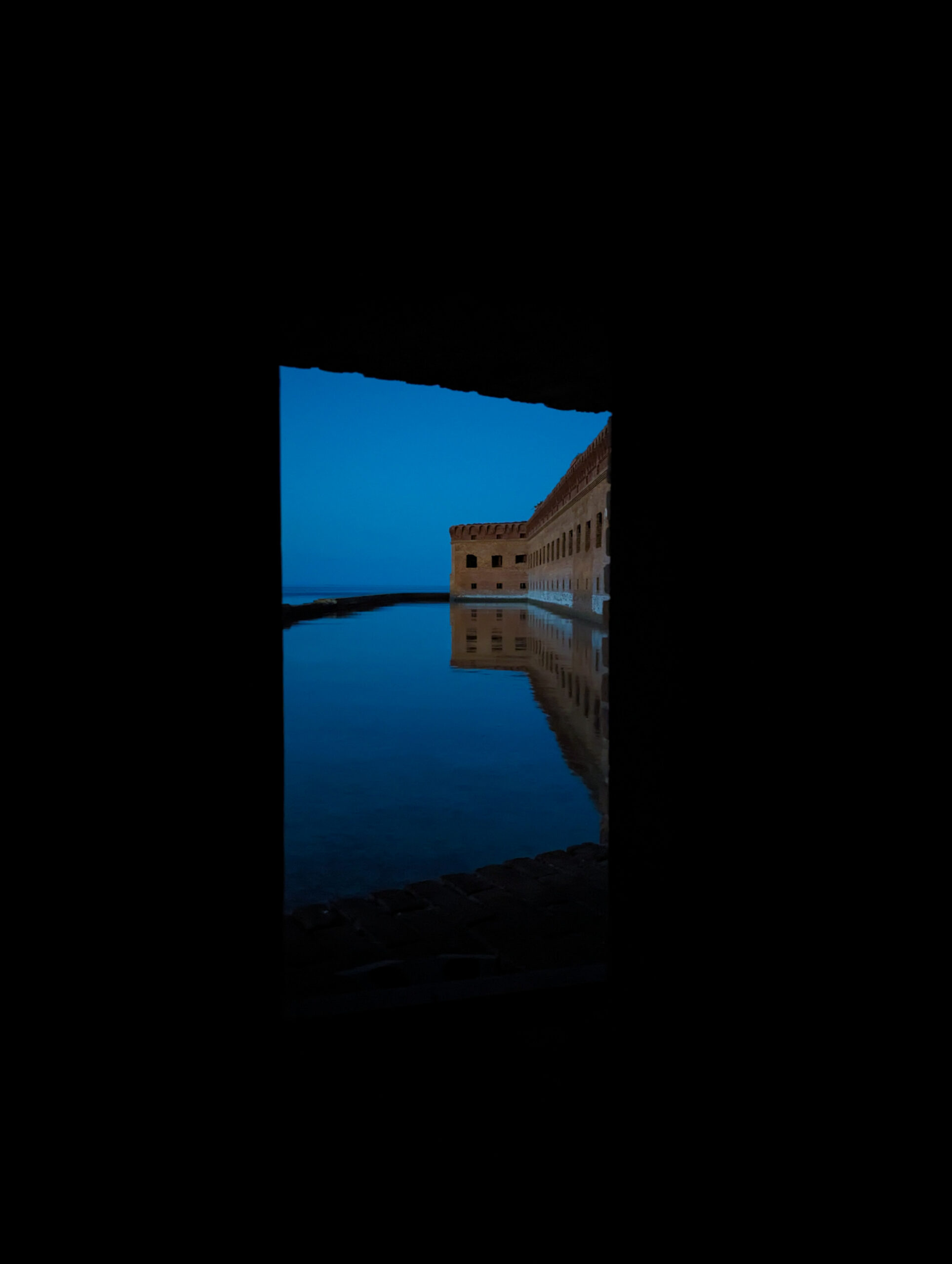

It takes us four hours to make the crossing to the Tortugas. After leaving Key West there is the occasional mangrove-covered key and then nothing on the horizon but a brown booby chasing flying fish disturbed by our wake. Davis spots it first, a lighthouse on Loggerhead Key and then the low-lying unnatural structure on Garden Key. Fort Jefferson itself, a 19th-century brick-work fort. The channel circles around the west side of the key and we dock on the south. NPS folks lounge in the shade, ready to catch dock lines; boys fish off the pier, frigatebirds, and terns are circling overhead and it is hot. Rob Waara and I get in the water with our scuba gear to complete the open water portion of my Blue Card certification. I’m in swim trunks and a rash guard, it feels unnatural coming from diving in the Pacific Northwest. We submerge and immediately see a lemon shark. It’s a quick dive, I complete the tasks and climb up the ladder on the Twin Vee. “Dude, how’d you miss the Goliath?” Rob asks with a grin. “What!?” I jump back in with my mask. Sure enough, a goliath grouper is just hanging out right under the Twin Vee. I’m frothing, this place is rad.

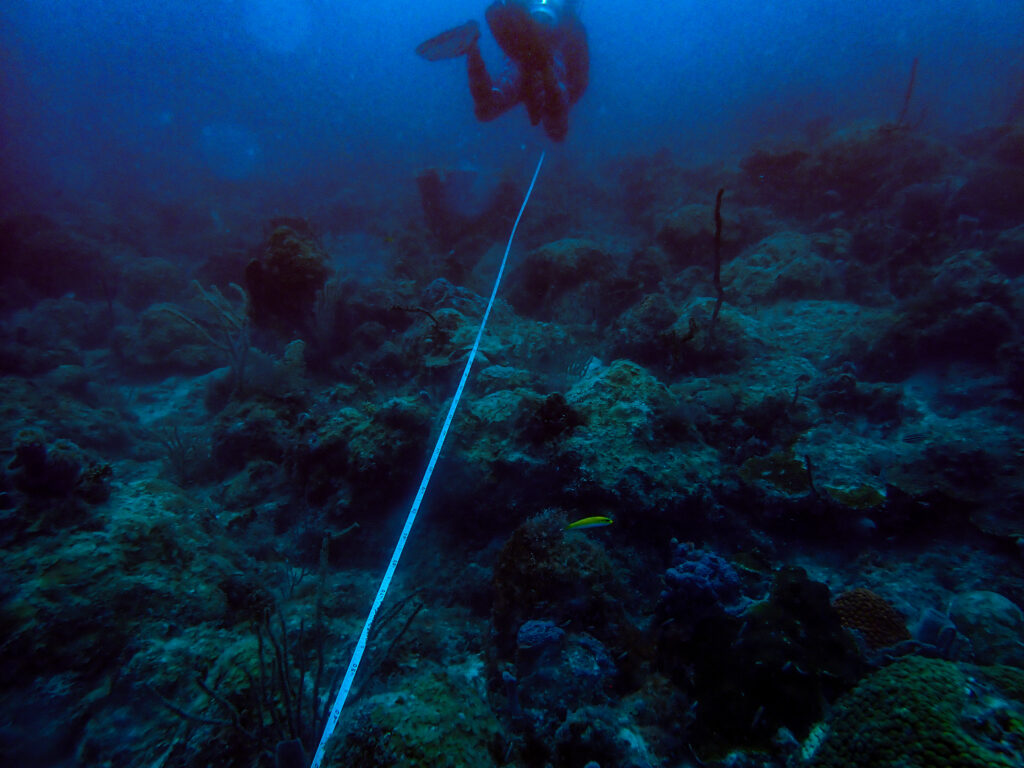

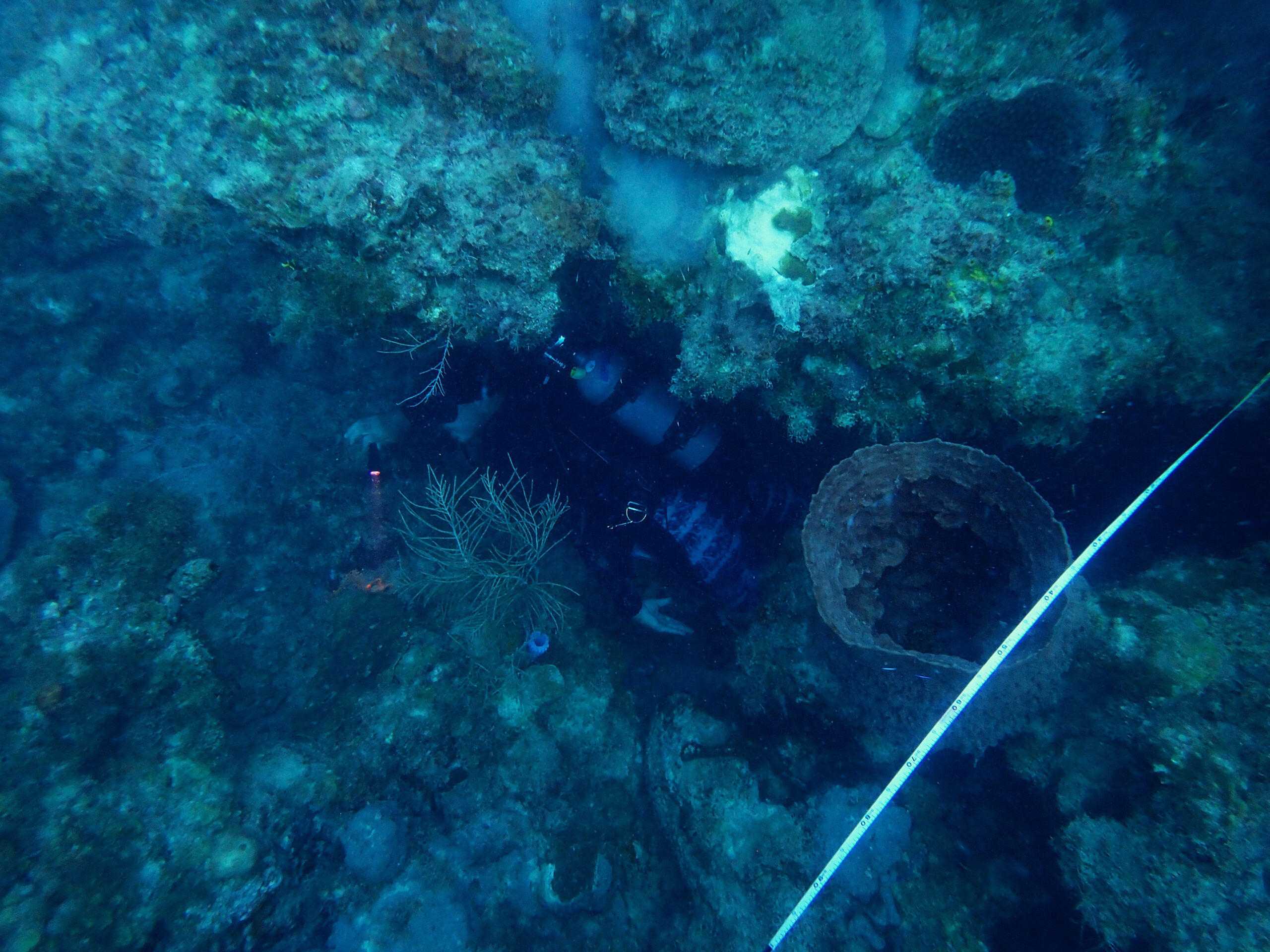

It’s day one of surveys and Lee gives us the briefing. The SFCN wants to hit more than 100 sites in the next 10 days. The sites are randomly selected and they can be anywhere there is potential lobster habitat. This means some sites are 80 ft. deep with towering, complex structures while other sites are in 10 feet of water with low relief hardbottom and rubble. On each dive, we will be surveying two side-by-side 15m diameter plots. Each diver is responsible for searching for lobsters in their half of the circle and collecting abiotic data such as rugosity and percent cover of substrate for the whole survey area. Once a lobster is found, we estimate its size before we try to capture it with a tickle stick and net. We learn later in the week that this works best with help from your dive buddy. If we successfully capture the lobster, we can collect actual measurements of the carapace and more biological data such as if it’s a female with eggs.

These first couple of days we are joined by DRTO divers Karli Hollister and Amelia Lynch. Since there are eight of us, we split the crew between two boats. I am in the Munson, the DRTO dive boat, with Lee, Karli, and Davis. We head to Pulaski shoal to find some lobsters. I submerge and am immediately distracted by all of the fish, gorgonians, and sponges. For the last couple of years all my diving has taken place in the Pacific Northwest so I’m feeling a little spoiled to be diving with no weight, no dry suit, and the ability to see more than five feet in front of my face.

Luckily on this first dive, we find a lobster and all get the chance to practice capturing it. I learn that with the tickle stick, you want to get it behind the lobster and give them some gentle pressure on their tail so they slowly walk forward out of their hidey-hole, and then you can get the net behind them. If you’re too aggressive they may take off backwards with their powerful tail and you might not get the chance to catch them again as they move deeper into their cave.

It’s a daily fun surprise to see what kind of habitat we’re going to get as we explore all over the park. We’re out on the water from about 9 to 4 every day. While the Munson crew is cruising with six to eight dives, the Twin Vee crew is busier, getting in ten dives a day. Some days I catch a couple lobsters, other days I don’t see a single one.

It’s so difficult for me to not get distracted by all the fish on our dives. I feel lucky to have Lee, the fish expert, to answer all my questions. You can almost count on having a friendly red grouper every dive hanging out and checking out what’s going on, trying to eat the juvenile lobsters you’re trying to measure. The SFCN crew tells me that I won’t see big fish like the ones here down in the Virgin Islands.

On our second day, Lee and I have an incredible site with dense coral coverage, which also makes it difficult to search. We’re upside down, peaking under the ledges and shining our lights deep into the caverns. Lee points out a beautiful spotted spiny lobster (Panulirus guttatus) which we are also counting in our data. They are much harder to spot as they always seem to be as deep as possible in their cave and holding onto the ceiling.

Day four and we’re hitting our stride and have a couple of logistical successes. Brian fixed the water maker on board the Fort Jefferson, and the Makai, the other research vessel supporting the DRTO divers is rafted up to Fort Jefferson; she has an air compressor on board and fills all of our tanks with Nitrox which will help us hit more of our deep sites.

On day five, Karli and Amelia go back to Key West, and Mike, Rob, Lee, Davis, Allison and I are all on the Twin Vee for the rest of the trip. The Munson crew is now in the big leagues. Mike gives us the morning briefing, dive plan, and point of contact on DRTO and Davis gives us the weather. As a PNW boy, these tropical storms are fascinating to me. You can see the thunderheads form when you’re out on the water and today we got a good one. Halfway through our dive day an ominous wall of darkness and rain in the east forms and starts heading towards us and the fort. Mike checks the live weather forecasting and sees a blob of red and lightning bolts. “That’s not good” he says, and we speed back to the fort watching a waterspout form and touch down in the distance. So crazy. We make it back to the dock as the wind picks up and the lightning and thunder arrive. I love the color of the dark sky and the churned-up green water, no longer that tropical blue.

After a full day of dives, when we return to the dock, Rob and Allison usually go fill tanks while the rest of us organize data sheets, rinse gear, and prepare for the next day. In the later afternoon, only NPS staff and campers are left on the island and this is when I get to wander the Fort and snorkel the moat wall.

Fort Jefferson was built between 1846 and 1875 to protect the shipping channel between the Gulf of Mexico, the western Caribbean, and the Atlantic Ocean. Supply and subsidence problems and the Civil War delayed construction and the fort was never completed.

I would say Dry Tortugas is inhospitable for humans. Any place where you must bring in fuel to run generators in order to run AC for people to survive is a harsh environment. I feel like I’m always getting too much sun and not enough water. It’s even too hot to fill SCUBA tanks in the middle of the day as the air compressor will overheat.

I wander the different levels of the fort imagining the massive undertaking and slave labor it took to lay each one of these bricks. While it’s too hot for me, some of nature has found its niche and a way to survive. I love the Buttonwood trees that fill the inside of the fort, they’re so gnarled, I wonder how old they are. Right next door is Bush Key with its constant cacophony that is hard to ignore; the only significant nesting colony of sooty terns and brown noddies in the continental US. After dark, Brian loans us interns a blacklight and we go hunt for scorpions in the bricks of the fort. Allison and I also go for a night snorkel around Garden Key and the moat wall to see basket stars and octopus. Brian set up an outdoor shower on the deck. There is something really special about taking a cold shower in the warm night air with the stars, loud birds, boat generator, and flashes of lightning all around in the distance.

It’s day seven and Brian gets us going with his good morning playlist. We’ve gotten into a good rhythm; we will get nine dives a day on the Twin Vee and the weather is behaving. We have multiple days of glass out on the water which means the 90-degree air temperature is that much hotter and it’s a relief to jump into the 86-degree water. The Twin Vee bumps the tunes on the surface intervals, I made the mistake of changing the channel from the Dave Matthews Band while Mike was enjoying them, he was shocked (sorry Mike). Snacks also become very important. I look forward to the Wickle pickles on my sandwiches and the frozen peanut butter m&m’s for when we finish the day.

“Let’s get them bugs!” becomes our mantra. I really enjoy the dives on the west side of Loggerhead Key. There are some deep, murky dives with big rocky formations. It becomes known as Mordor. You see lots of fish and the occasional Goliath grouper. It is sad to see the massive coral heads covered in algae and biofilm. Mike points out brain corals, 100s of years of growth now dead, wiped out by coral disease just within the last few years.

Day nine and Mike and I have our most lobster-heavy dive of the trip. Bug City is on a rock wall. The outside edge of our cylinder plot was around 65 feet deep where the wall hit the sand and then the other edge of the cylinder was in 35 feet of water. It’s murky and the wall is full of caves that you can’t see the end of. In total, Mike and I find 12 lobsters on this dive. It was exhilarating. Mike found a large lobster molt that we brought back to the surface and added to our other mascot, Larry the lobster, created by Lee from the foil of our sandwiches. A fisherman gives Brian a bucket full of yellowtail and Brian generously shares his fish with us. Lee and Rob filet, while the Goliath groupers and Lemon sharks come to snack at the cleaning station. We have a nice big family dinner. All week we have been sharing dinner duties. Davis, Rob and Allison make a mean Thanksgiving dinner and Brinner (breakfast dinner). Lee does burritos and Mike ‘cheffed’ it up with his first red curry. Tonight Rob makes an awesome ceviche and Brian uses his Ninja to fry up some fish with a mix of TJ’s hippie chick seasonings. The big lobster molt is our center dining piece.

I catch one last sunset from the top of the fort; watch the tarpon patrol the outside of the moat wall, the Frigatebirds coasting overhead, the sooty terns serenading with their cacophony of voices. In total, we dived 106 sites and recorded 131 lobsters. At first glance, the lobster population density looks similar to Biscayne, but the lobsters in the Dry Tortugas appear to be a much larger average size. We’ll see after the data is analyzed. This is an amazing national park and one I didn’t even know existed before I got this internship. To be able to work with the SFCN and conduct surveys that will have an impact on lobster management in the future has been a dream. Such a solid team of professional, hard-working divers who also know how to keep it light and fun. Mike, thank you so much for inviting me on this trip and to take part in some of the amazing work you do in the national parks. Rob, Lee, Davis and Allison, thank you for taking me into your dive family. I had so much fun working and learning from all of you. Thank you Brian for your hospitality and letting us take over your boat for ten days. And thank you OWUSS and the SRC for providing the support to make all of this happen. I had the most amazing time in the Dry Tortugas National Park and I can’t wait to keep exploring the Caribbean! Check back for the next blog as I head to St. John in the US Virgin Islands.

As I am writing this, I’m thinking about the fragility and the resiliency of this amazing ecosystem. A week after I was at Dry Tortugas the Florida Keys recorded their highest sea temperature on record with multiple days in a row of water temperatures above 90 degrees.

Great post, fun photos and text. My only recommendation would be to include more information on the ecological significance of the work you are assisting with. For example, spiny lobsters are keystone predators in marine ecosystems and coral reefs with healthy populations of lobsters are very different than without healthy populations of lobsters. While you definitely emphasized the fun factor of all of this, people also need to learn about the ecological role of the species you are helping with research on.

Keep up the great work and I will look forward to learning something more at your next underwater visit.

Thanks David! I agree with you and appreciate the recommendation. I will work on including more science in future posts!