On my stopover on Oahu, I meet up with Shaun Wolfe, 2017 OWUSS NPS intern, who graciously hosts me for the night. We paddle up Kahawai Nui, do a little waterfall hike, and volunteer for a Maui fire relief donation center. He sends me off to the Big Island and my next national park destination, Kaloko-Honokōhau National Historical Park. I fly into Kona, pick up my rental car, and head to my hostel. I will be meeting the park divers tomorrow morning at the office.

Kaloko-Honokōhau is a cultural and natural park focused on preserving ancient Hawaiian culture. The park protects two fishponds, a fish trap, burial sites, settlement ruins, and the marine nearshore. Nowadays, the park feels like a refuge encircled by development. A relatively small area, it is surrounded on three sides, a resort to the north, an industrial complex to the east, and a busy working harbor to the south. The reason this area is protected is because a group of Hawaiian elders in the 70s recognized the importance of preserving the area and its historic land use, and had a desire to perpetuate native Hawaiian heritage and culture. They approached Congress with a proposal and plan for management, and the park was created.

Currently, the resource management team is working to monitor the nearshore marine environment, restore the ancient fishponds, and re-establish native Hawaiian plants. Another major focus is allowing the native Hawaiian community to reconnect with traditional practices.

I meet Kaile’a Annandale, biological technician (but basically acting marine ecologist since she is running the entire marine program), and Lily Gavagan, a summer dive intern from UH Hilo. I’m jumping right into diving with them, so I get the rundown of what we’re doing as we drive to the park to pick up the boat and Jackson Letchworth, terrestrial biologist and boat driver for the day.

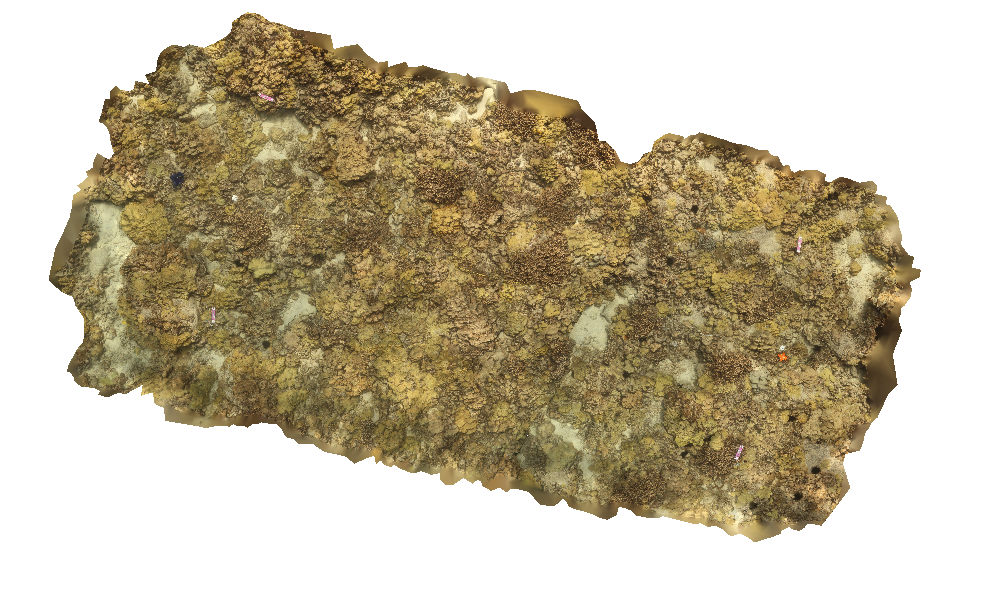

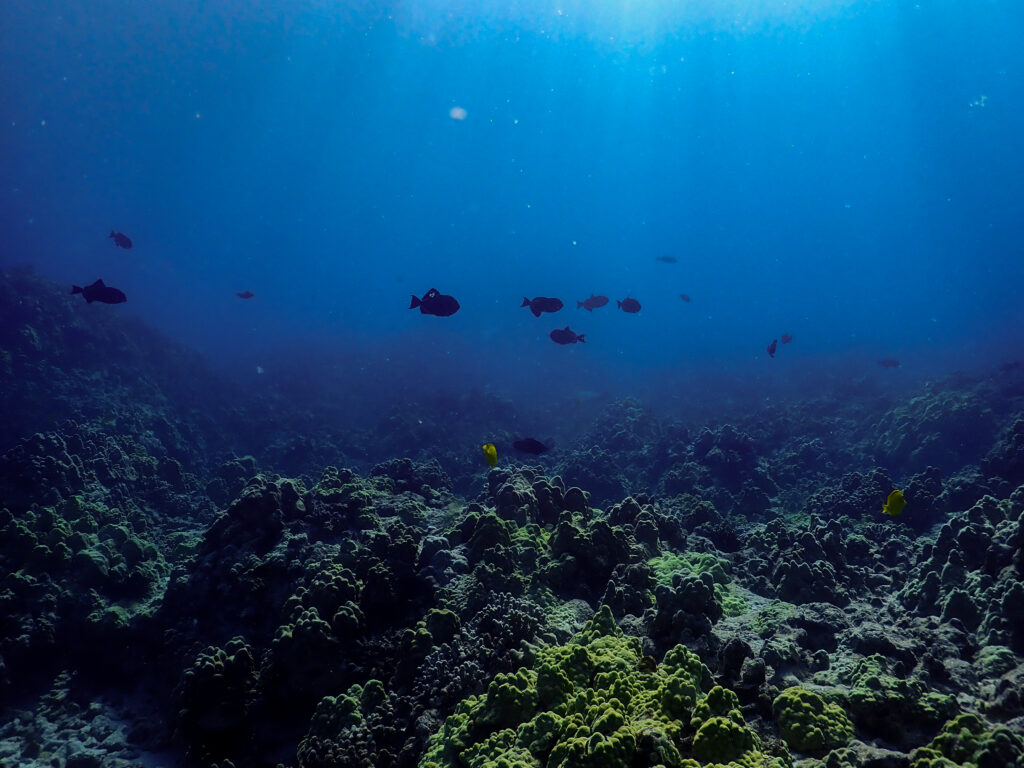

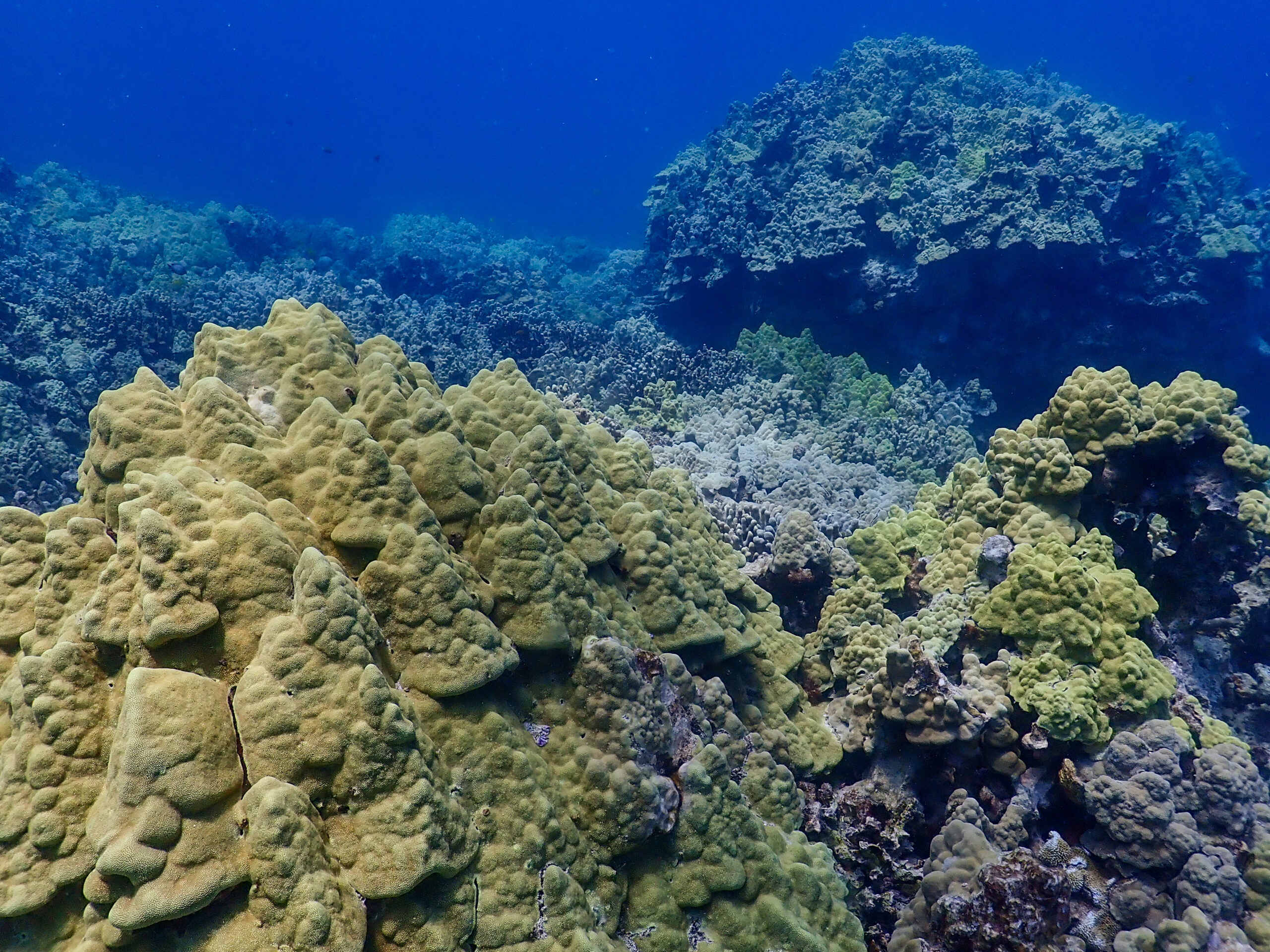

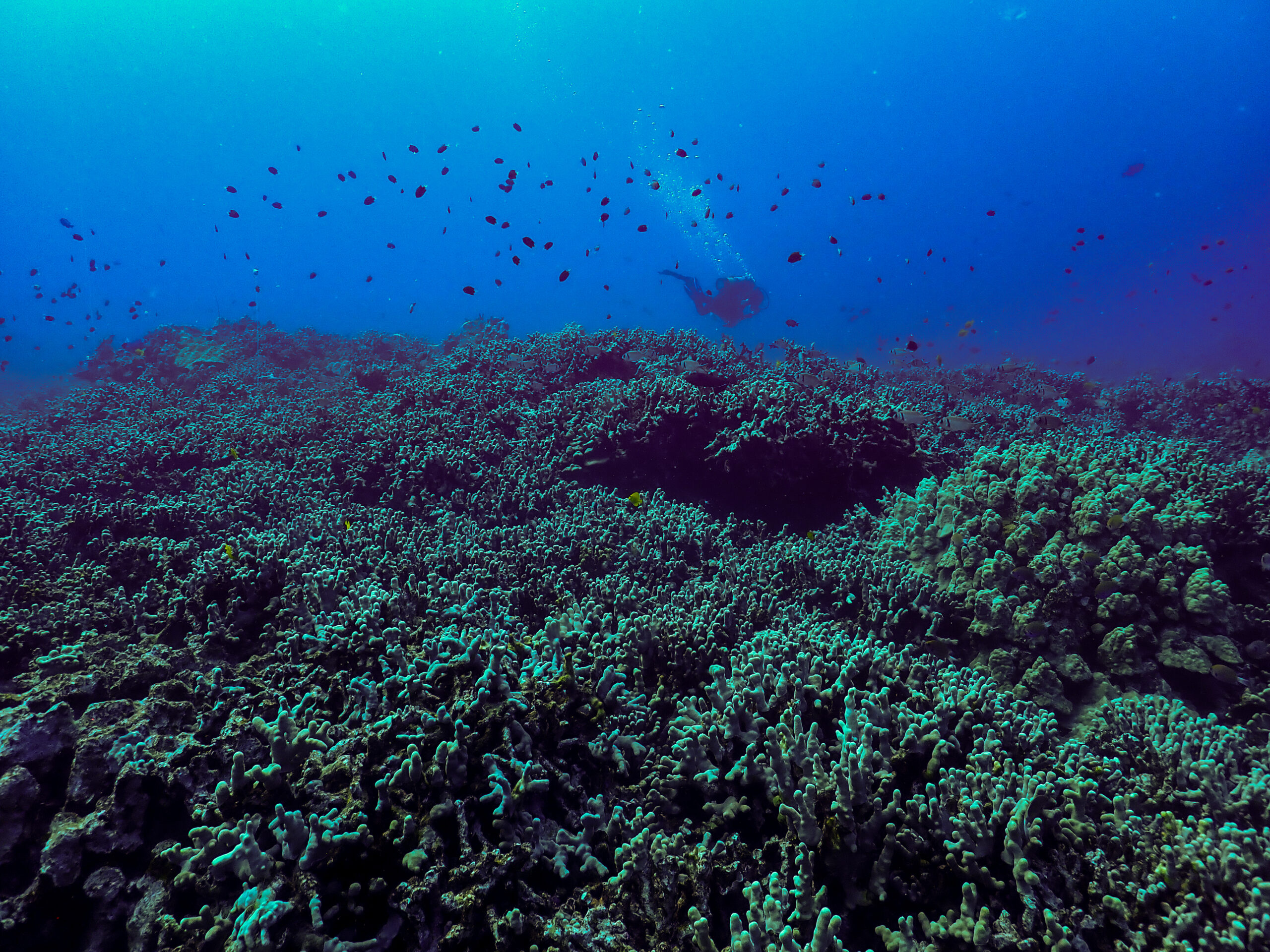

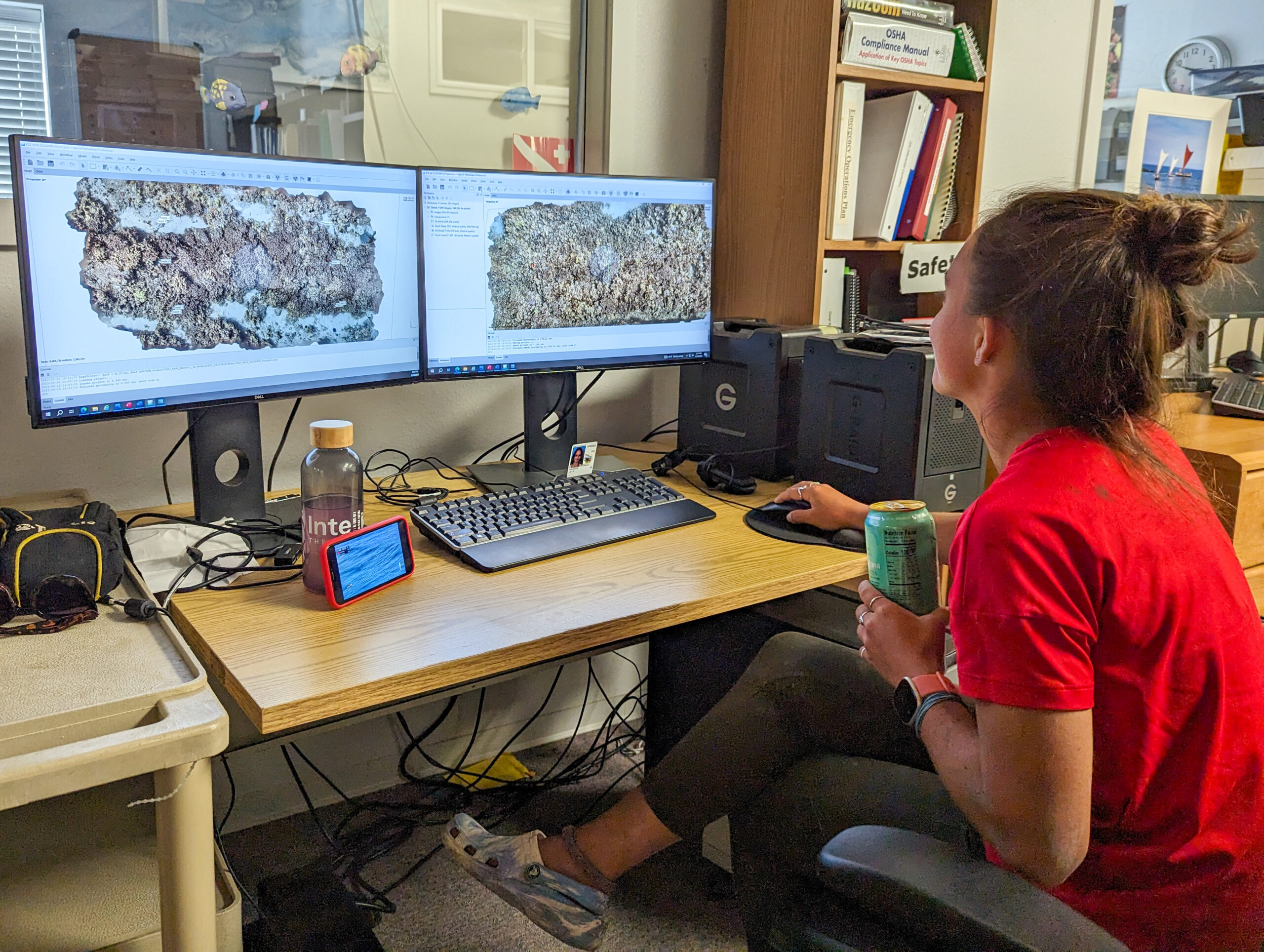

The park is conducting its yearly benthic surveys at sites in park waters to monitor the status of the marine environment. It is important to have robust data to track trends and better inform management of the resources. This is especially important here where they are surrounded by urbanization, and in the past have dealt with pollutants and wastewater entering the nearshore from coastal development. The method for data collection is a bit different from other surveys I have taken part in this summer. Kaile’a uses a really cool technology called photogrammetry, where photos taken of the reef are stitched together to create high-definition, 3-dimensional maps of the survey site. A versatile tool: data collection is precise, fast, and non-invasive. There is a lot less human error. For coral reef monitoring you can overlay years of data to track changes. You can compare the coral growth rate at a site, how a disease has impacted the reef, or how the coral may be recovering. You can get precise quantification of surface area, surface relief, and volume. It can also just be a nice visualization of the reef.

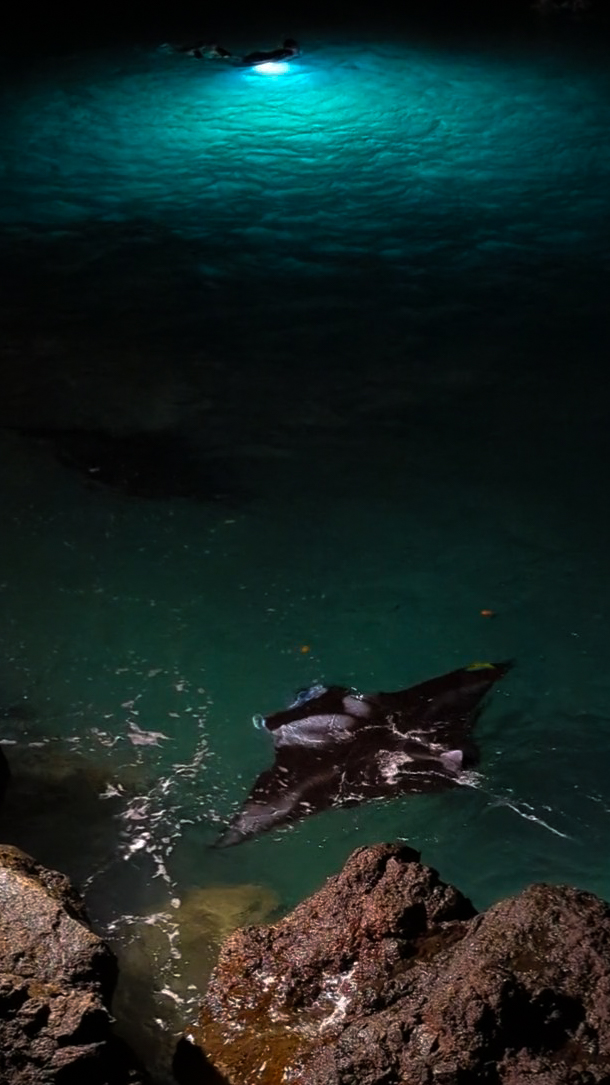

We launch the boat from the Honokōhau Harbor which is full of dive boats and fishing boats, both charters and commercial. At the mouth of the busy harbor, we are greeted by a pod of spinner dolphins. This body of water, dubbed Kona Lake is in the lee of the Big Island, with generally calm conditions so it’s very different than diving at Kalaupapa.

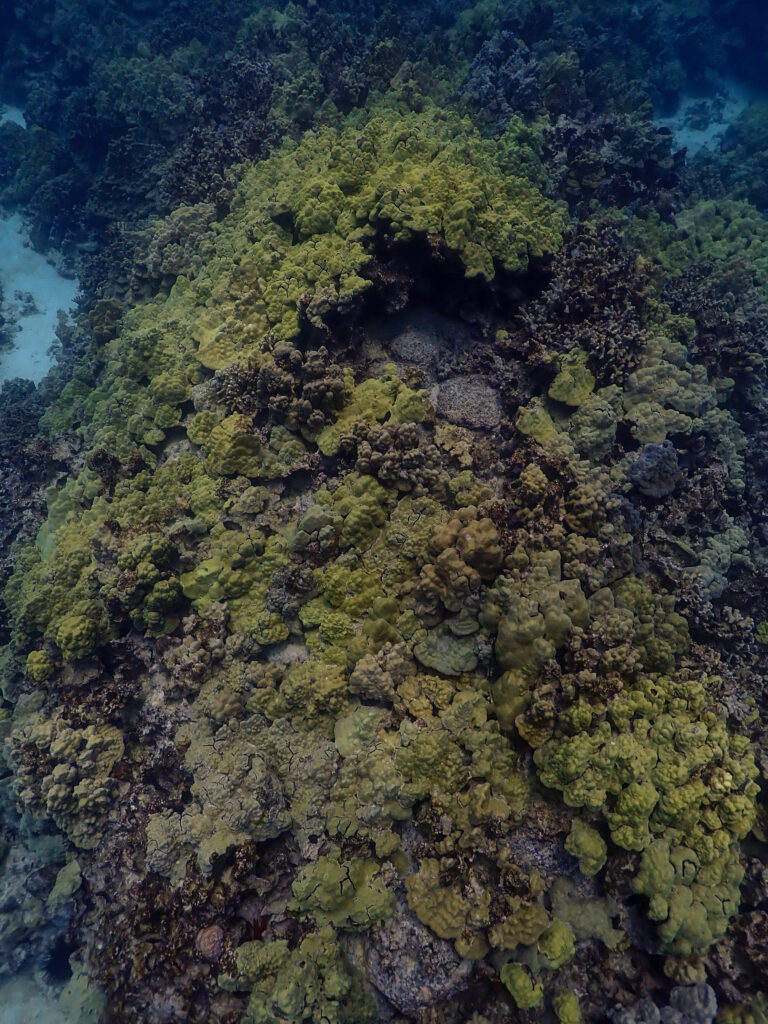

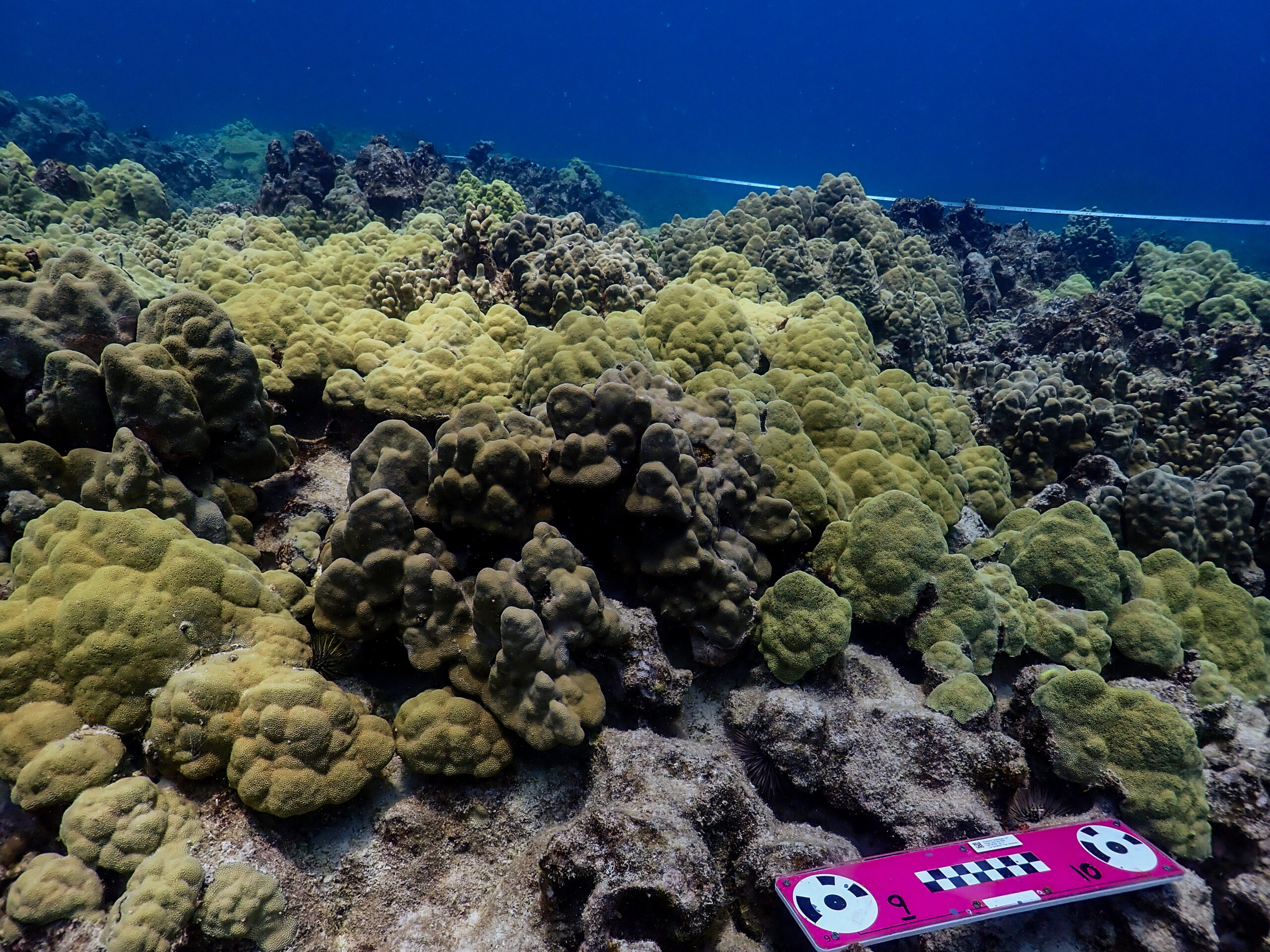

It’s my first dive all summer where there is pretty decent coral coverage. I’m impressed but when I surface and tell Kaile’a, she has a different perspective after diving here for many years. As I talked about in my last blog, there was a coral bleaching event here in 2015 that led to a massive die-off of coral, especially cauliflower coral. The cauliflower coral is highly susceptible to heat stress and bleaching and hasn’t recovered in West Hawai’i. There are healthy-looking Porites species though, and a lot of small and juvenile fish since they have plenty of habitat for hiding.

Just like Kalaupapa, there are rebar pins denoting the start and end of transects. However, these pins are much harder to find in the canopy of coral. We actually take a reem of photos with us underwater to orient ourselves. The photos are of the pins from each cardinal direction. Kaile’a is an expert at finding them, I just get massively turned around. Then it’s a fun puzzle after we finish the site to navigate to the next site underwater with just the bearing and distance from the site we just finished.

When we find the right pins, Lily swims the transect tape out 10 m. She then swims two passes over the transect counting urchin species including wana, collector urchins, and rock-boring urchins that are within a half meter on either side of the tape. In the meantime, Kaile’a and I are laying out the corners of the rectangular survey site, 2 meters from the center. The photogrammetry program will pick up the scales which will orient the 3-D model with known lengths. Kaile’a swims the rectangular site taking many photos of the bottom to get a lot of overlap which is necessary for good resolution. We get two dives in, haul the boat out, rinse it down, and finish the day.

Our next day has no diving but Kaile’a takes us to explore some of the terrestrial aspects of the park. When you look around Kaloko-Honokōhau, you wonder why Native Hawaiians would have settled here. The a’a lava that makes up the landscape is sharp, inhospitable, and seemingly barren. The secret lies in the presence of cool, brackish water pools that form in the lava fields near the ocean called anchialine pools. Anchialine pools are fed by subsurface groundwater and seawater which means they will rise and lower with the tides. Some will disappear entirely if the tide is low enough. These pools provided enough fresh water to support settlement here. Anchialine pools are only really found on the west coast of Hawai‘i Island. There is a small red shrimp endemic to these pools that has a lifespan of 15 years!

Native Hawaiians possessed in-depth knowledge of their natural environment and demonstrated great ingenuity in adapting to this seemingly inhospitable environment rather than trying to dominate it. Hawaiians oriented their land-sea use patterns to the water cycle. Their land divisions, called ahupua’a extended from the mountain to the sea. The regions are all connected. The ahupua’a provided everything the people needed to live off the land; resources from the sea, the lowlands, and the uplands. I think it is a wild coincidence that Kaile’a learned her ancestors are from the Kaloko ahupua’a and here she is in the present day stewarding the same land.

Kaile’a drives us down to the Kaloko Fishpond. Fishponds are a simple yet highly efficient form of fish farming. The two fishponds in the park were once the largest along the Kona coast and Kaloko pond was supposedly a favorite of King Kamehameha I.

To make a fishpond wall, stones are dry-stacked without the use of mortar to enclose the mouth of a small bay. The porous lava rock allows seawater to circulate and freshwater springs trickle in from the land, to create brackish conditions. Ponds were either stocked with juvenile wild-caught fish—such as striped mullet and milkfish, or the fish enter naturally through sluice gates. The gates allowed small fish to pass in and out but trapped those that lingered in the pond and grew too large. Fishponds ensured a dependable food source.

Fishponds fell into disuse as colonization altered life on the islands. Now the park is working to repair the stone wall and rehabilitate the pond in collaboration with a local community group. Today, there is a university class here and we will all be clearing invasive pickleweed. Restoration efforts are underway to once again enable Kaloko fishpond to be managed and used for aquaculture. Although the restoration team has a long-term vision of harvesting fish from the pond and improving food security for the community, the work is also about reconnecting with culture and the land through traditional resource management. Kaile’a points out the freshwater springs all around the fishpond, cold, clear freshwater. It’s nice seeing collaboration between the federal government and indigenous communities to accomplish a shared vision of preserving culture, tradition, and resources.

Unfortunately, around the park, more groundwater is being captured and pumped by development. With the excess extraction of freshwater, anchialine pools and the fishpond are becoming too saline to support the brackish species that depend on them.

Back to diving the next day, I start my day off with a bullet coffee with local Kona beans. Jackson and I talk about how the park decides which plants to focus their restoration efforts on: native plants that were here before Polynesians arrived, or culturally significant plants like taro and breadfruit (ulu) that were brought here by the waves of Polynesians but are non-native. Definitely interesting to think about. We launch the boat in the harbor and head out for my last day of diving with the team. I really want to see Laverne today. She is the resident tiger shark that roams this area and divers and boaters often see her, sometimes even in the boat harbor. Unfortunately, she doesn’t make an appearance, but we catch our stride as a dive team and get 5 sites completed on one tank by navigating between them underwater. I’m definitely the weak link because I don’t think Kaile’a or Lily actually breathe when they’re underwater. A good dive day, I’m happy I could help this team get some more dive surveys in this season.

A short but amazing week here at Kaloko-Honokōhau. It was a pleasure diving with such a solid crew of kind and hard-working individuals. Thank you Kaile’a, Lily, and Jackson for being so great and sharing your park with me! I loved my time at Kaloko and I really look forward to coming back and exploring more of the Big Island someday. Thank you Submerged Resources Center and the Our World-Underwater Scholarship Society.