I’m happy to be back on the West Coast. I am in Ventura, California to join the Kelp Forest Monitoring (KFM) team at Channel Islands National Park for one of their 5-day kelp cruises. As one of the parks I hoped to visit most during my internship, I’m very excited to get the opportunity to dive here.

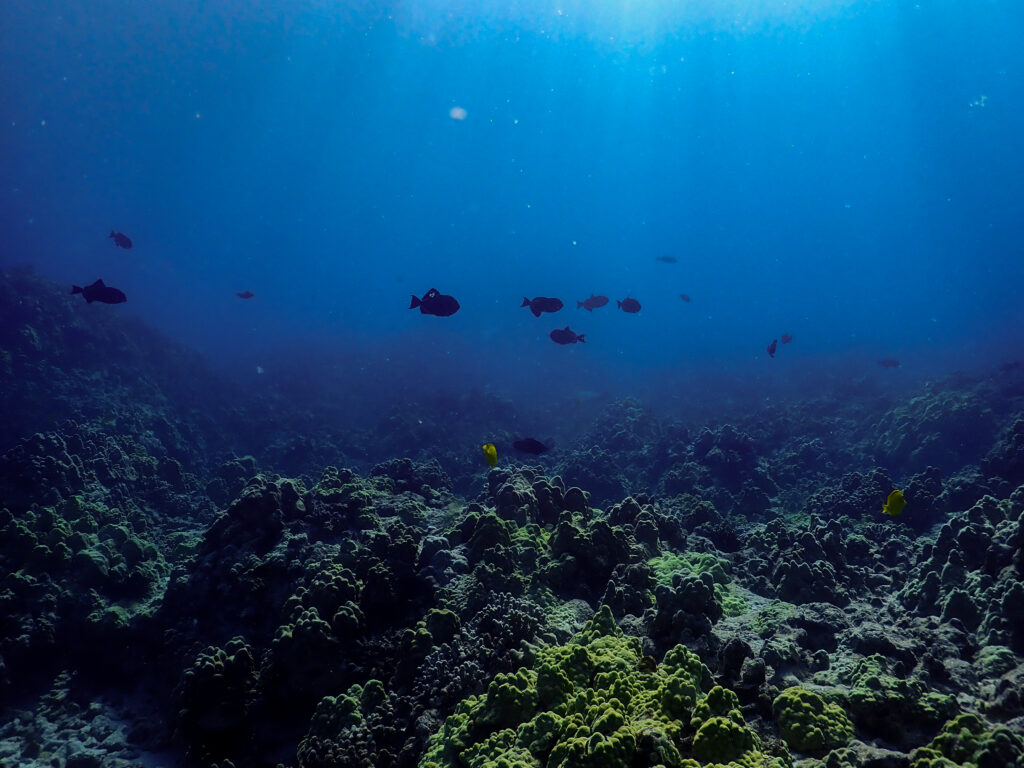

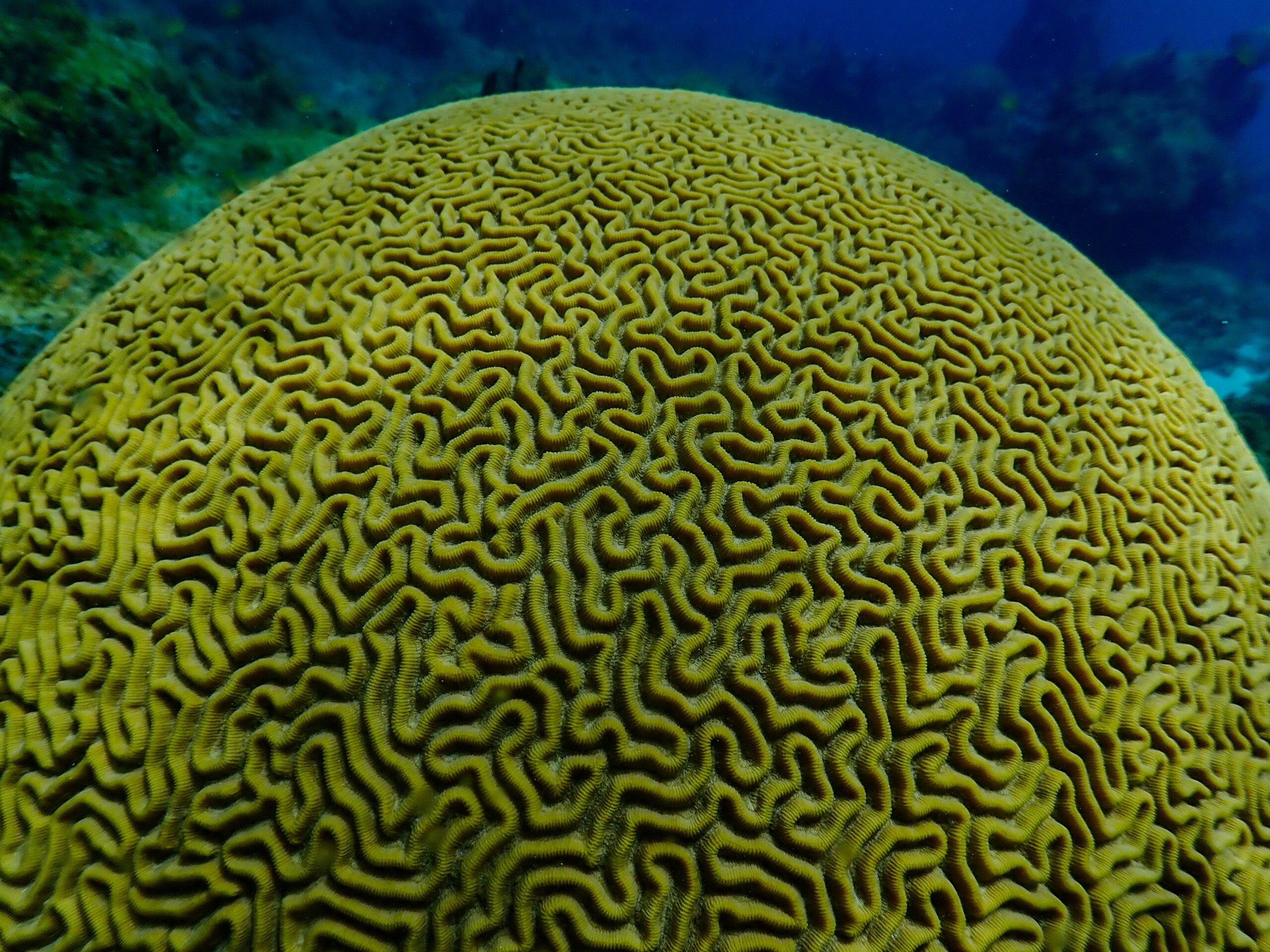

1/3 of southern California’s kelp forests are found within the Channel Islands National Park and Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary. The southern California coastline is one of the most productive on Earth and the islands are located at a confluence of currents; experiencing a mixing of both warm-water currents from the south and cold-water currents from the north supporting an incredible abundance and diversity of marine life.

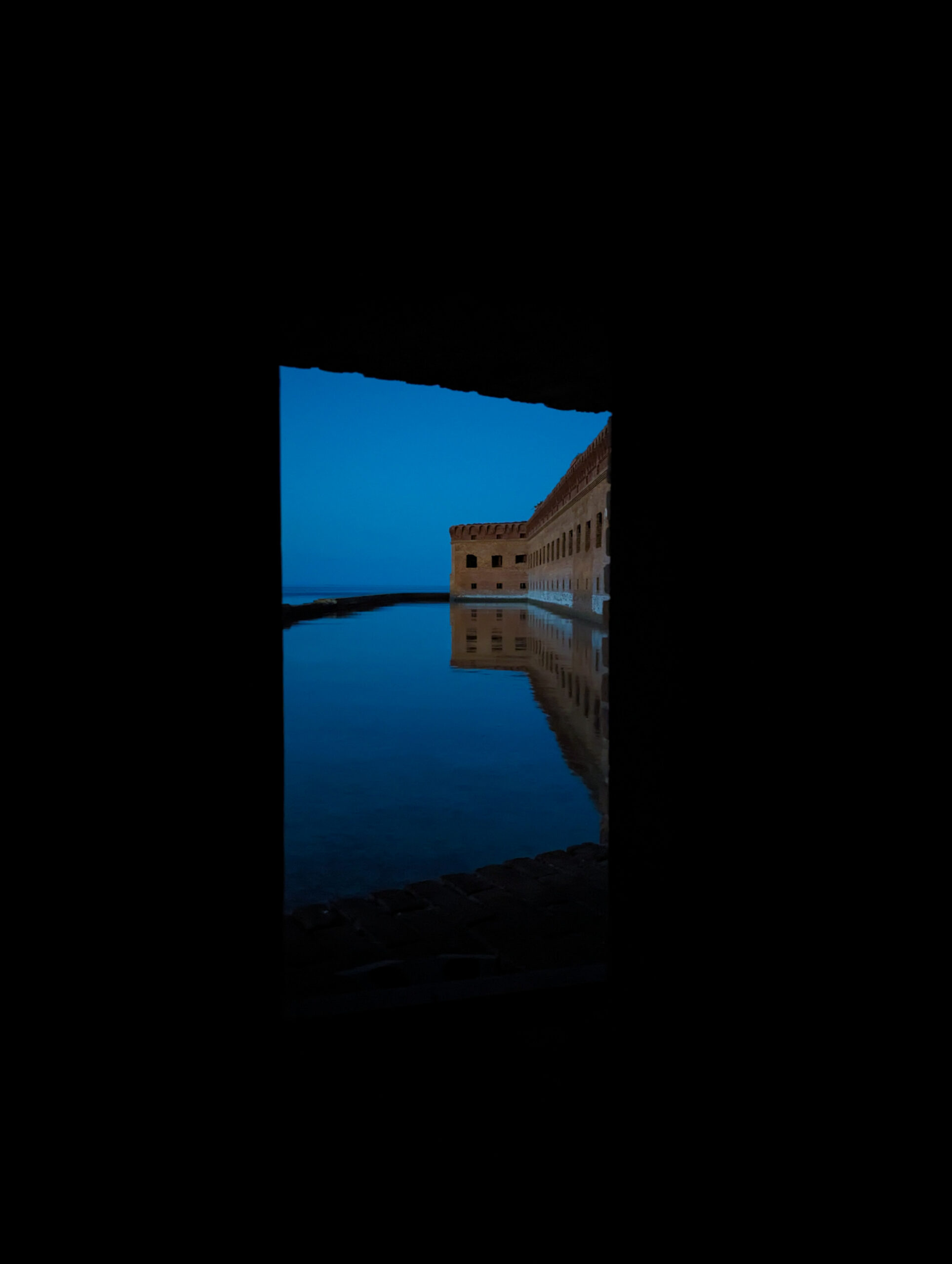

The Channel Islands National Park is made up of 5 of the 8 Channel Islands that sit off the southern California coast. It’s crazy to me that the park is one of the lesser visited parks in the country despite its proximity to one of the largest metropolitan areas in the US. Despite its low visitorship, Channel Islands is not immune to the many anthropogenic impacts on the marine world, one of the largest here being the pressure of commercial and sport fishing. Channel Islands has been monitoring the kelp forest ecosystem since 1982. The long-term dataset helps determine the status and health of the Channel Islands kelp forests, document the types of changes occurring in the marine environment, and develop management strategies to protect the kelp forest ecosystem.

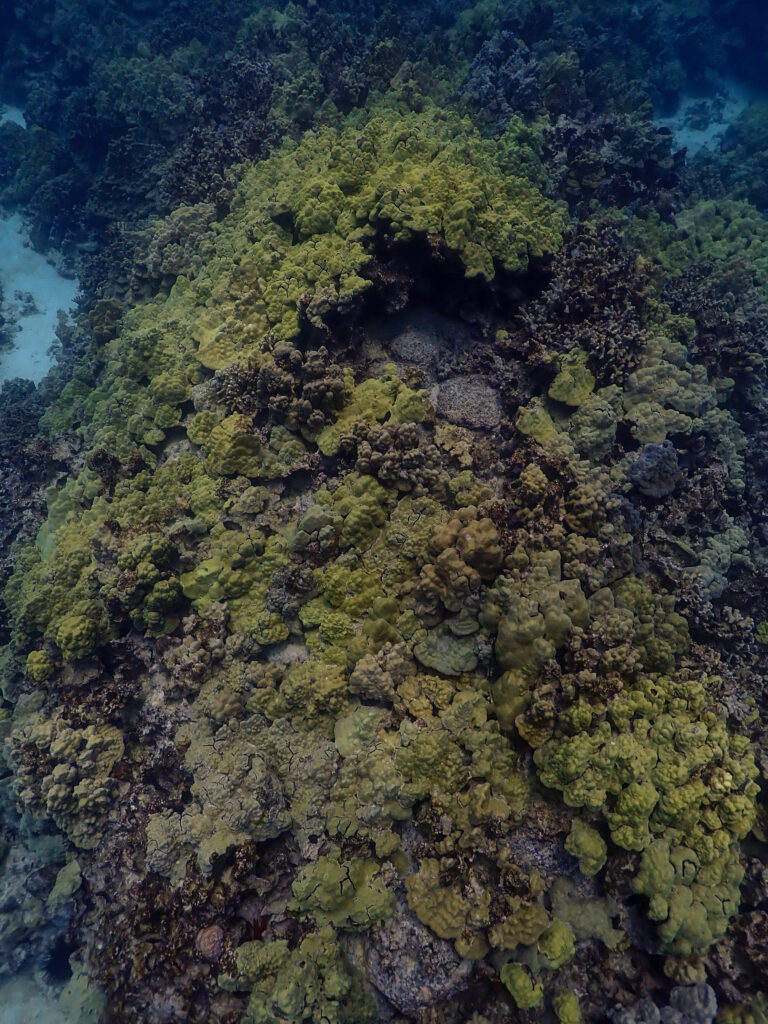

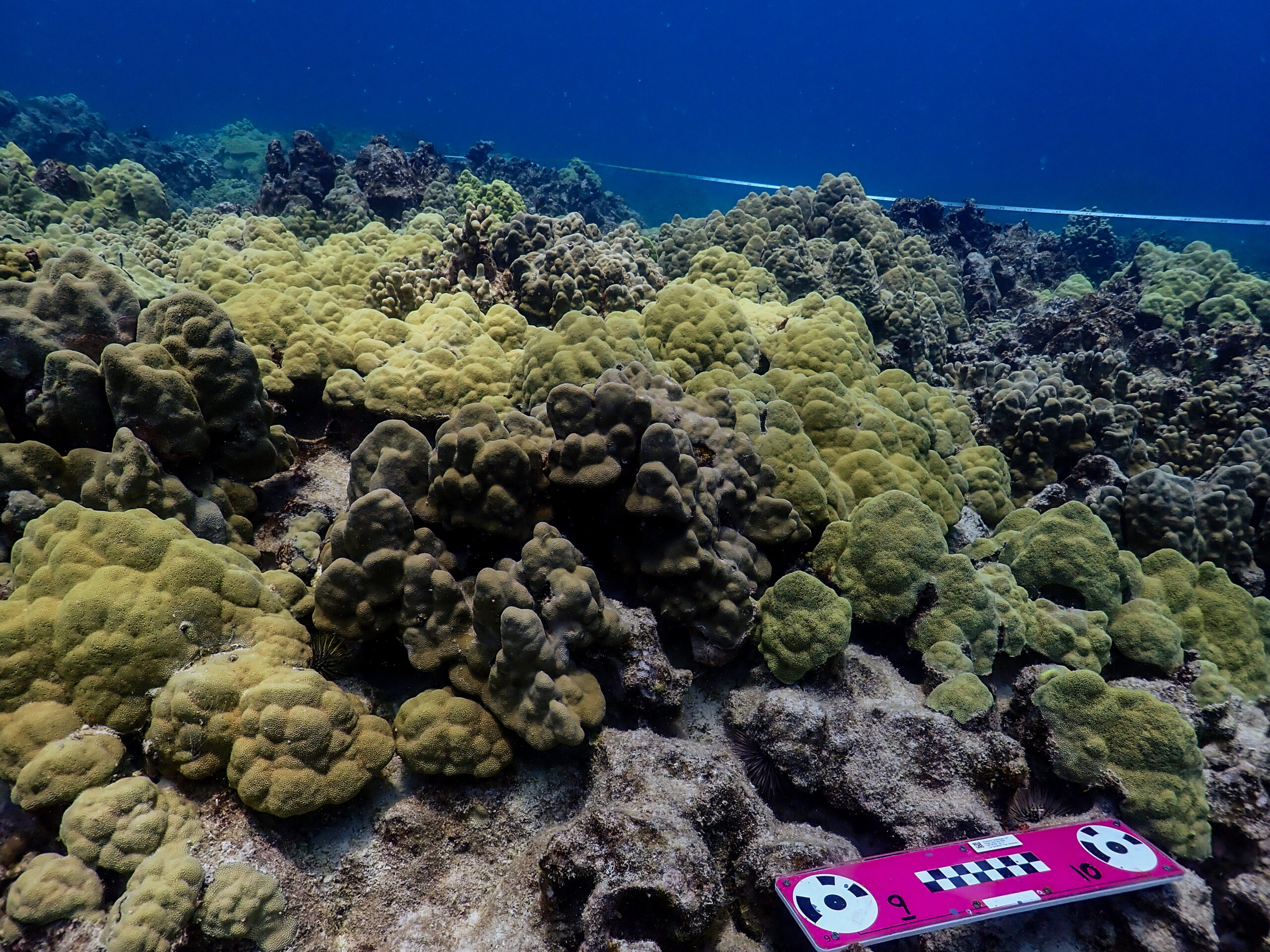

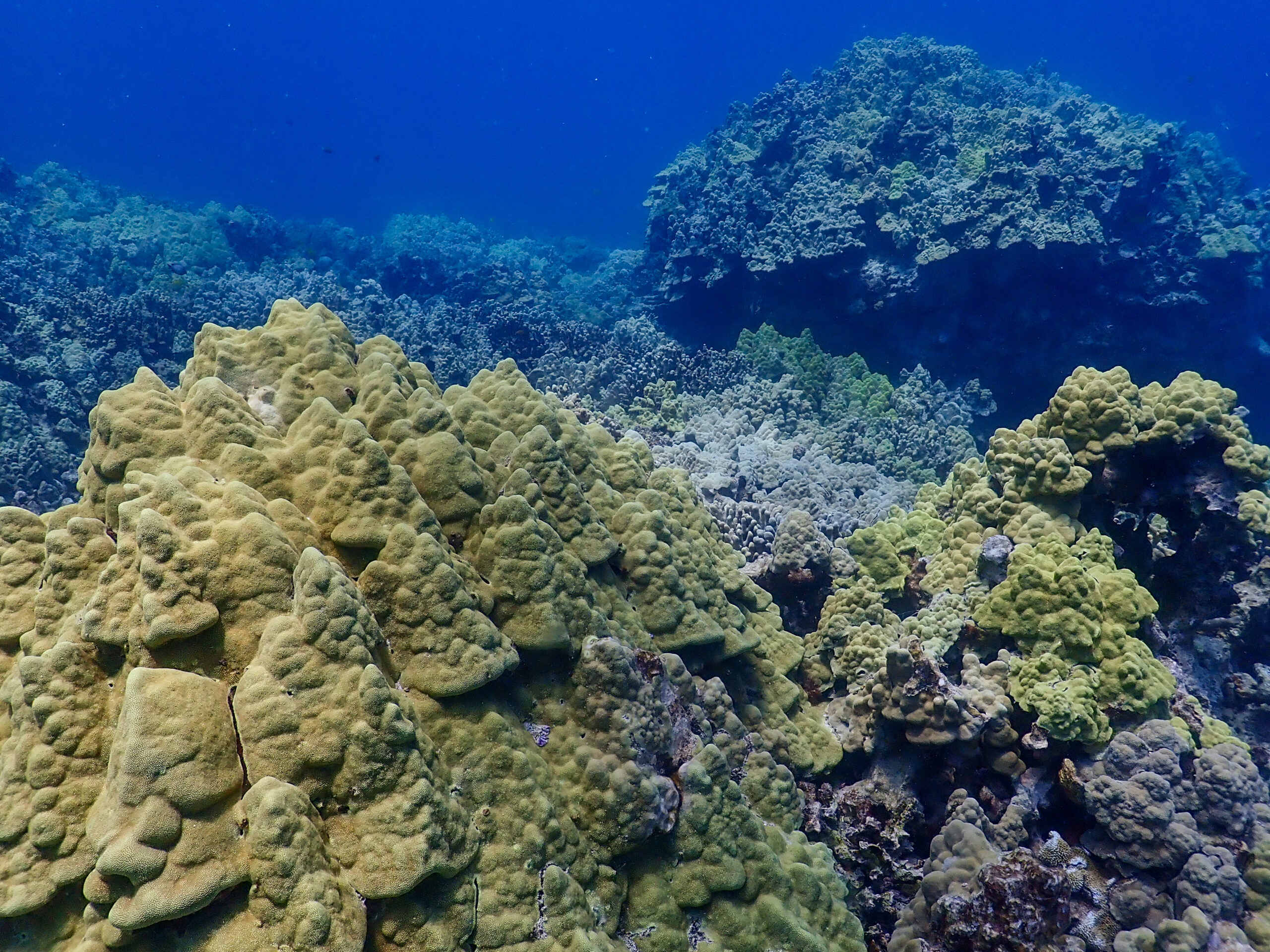

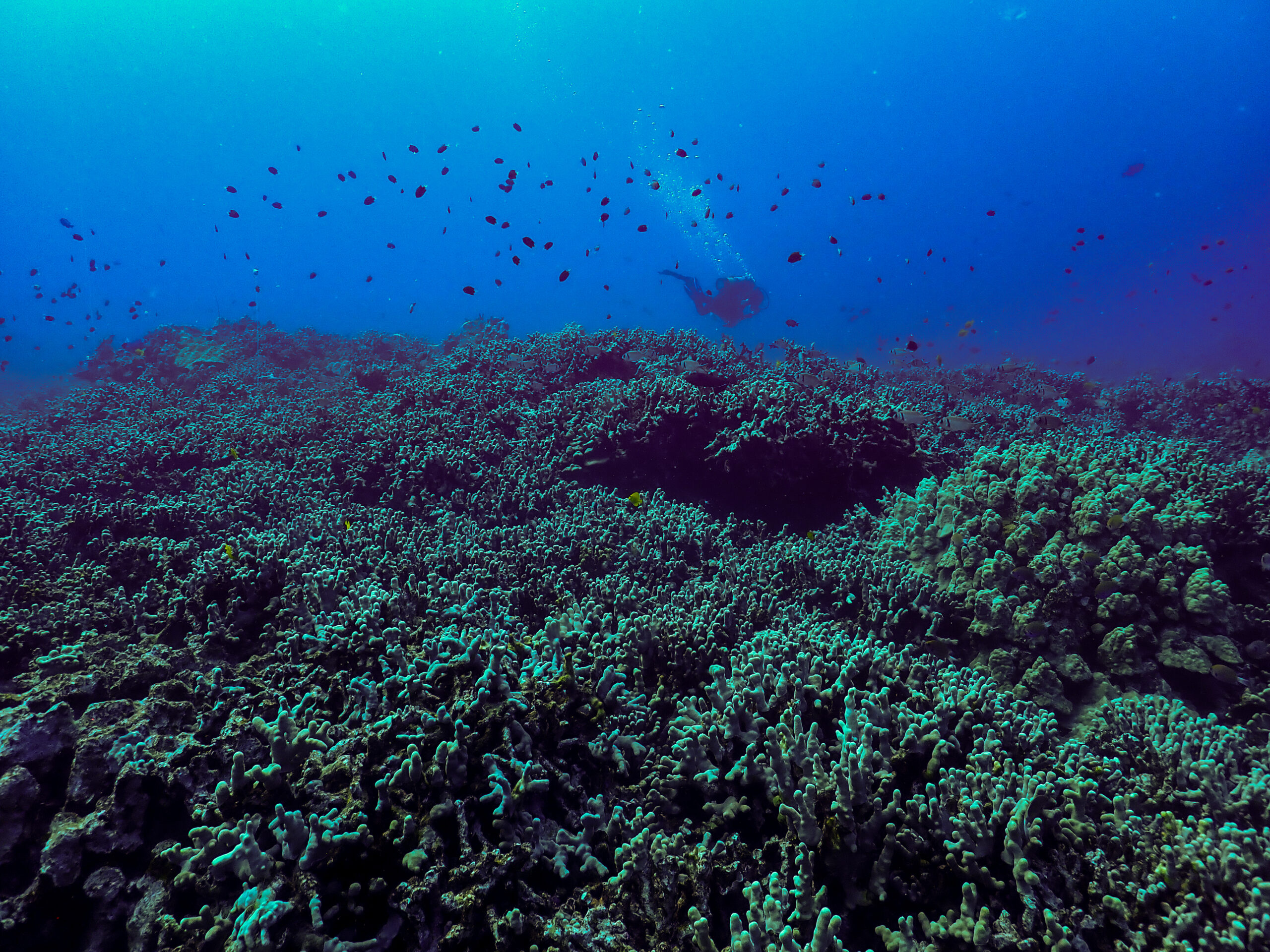

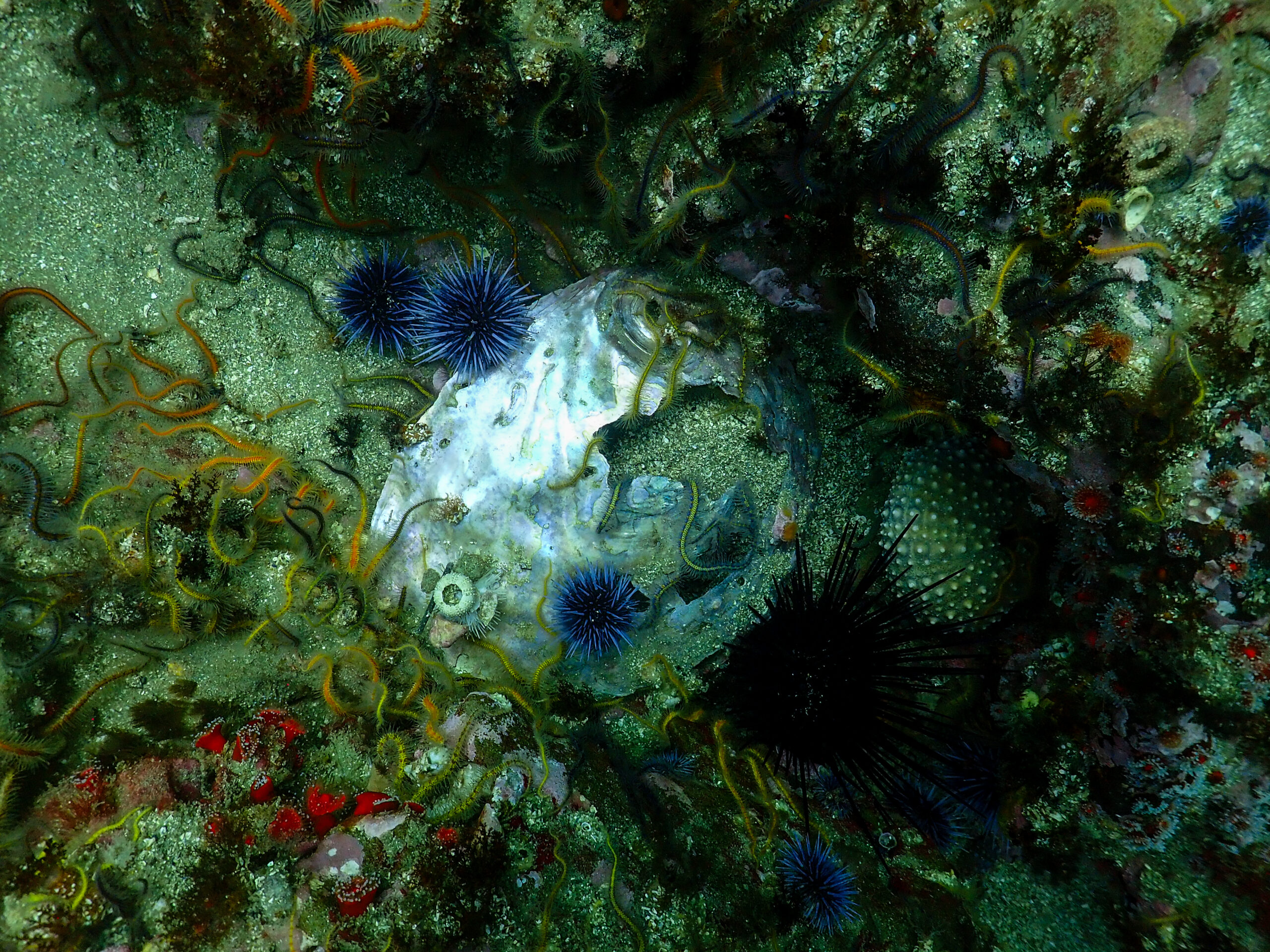

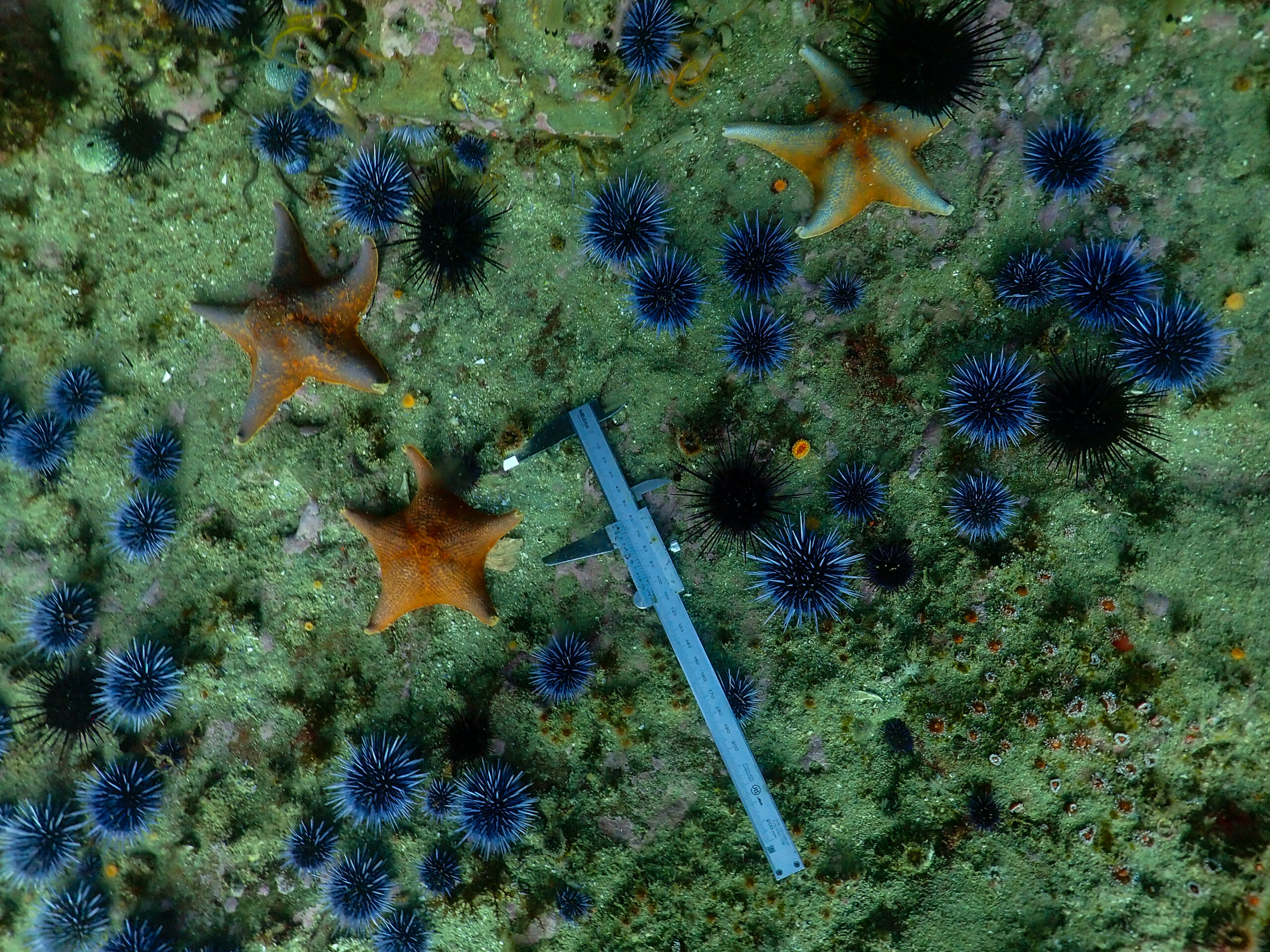

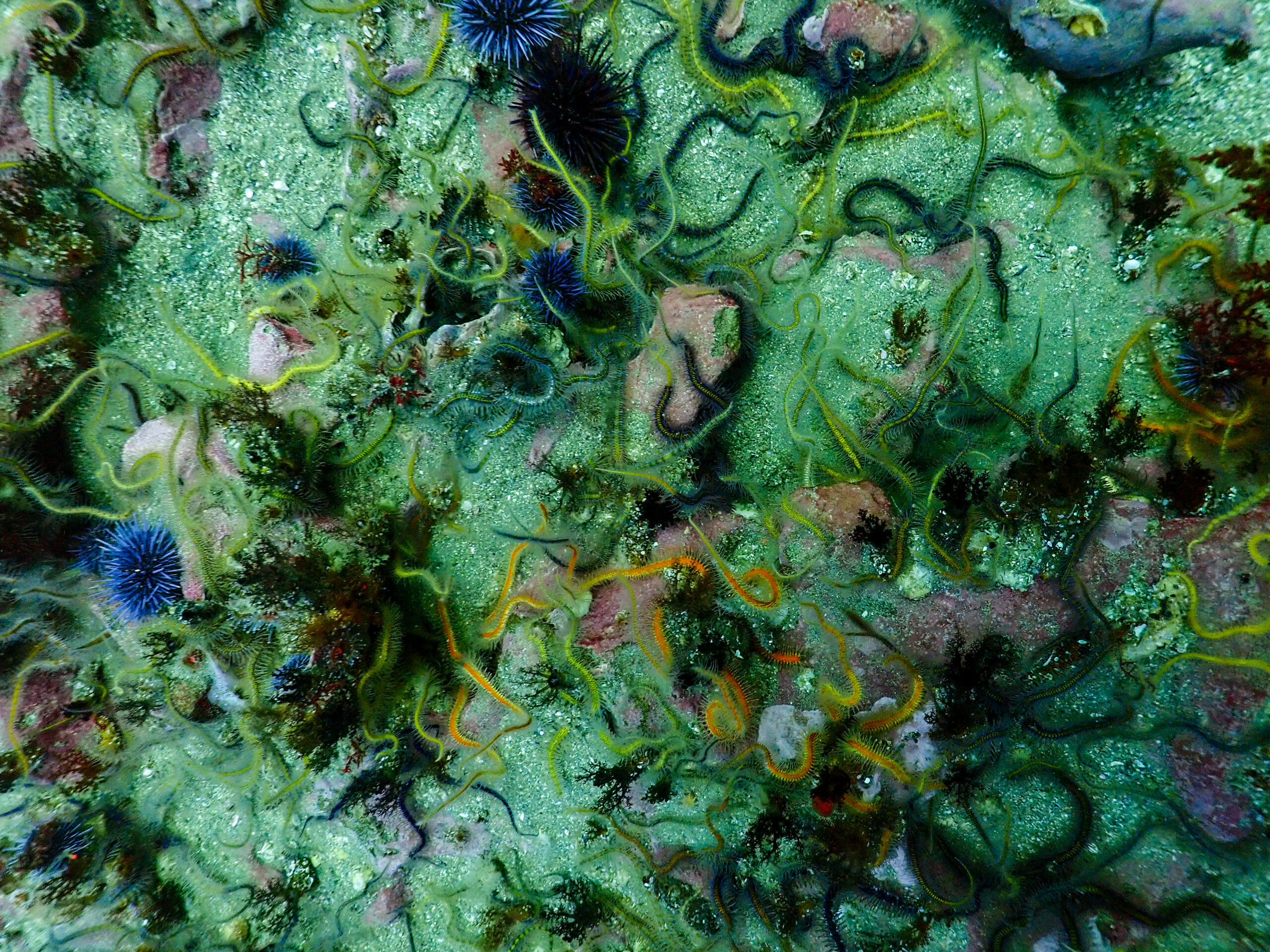

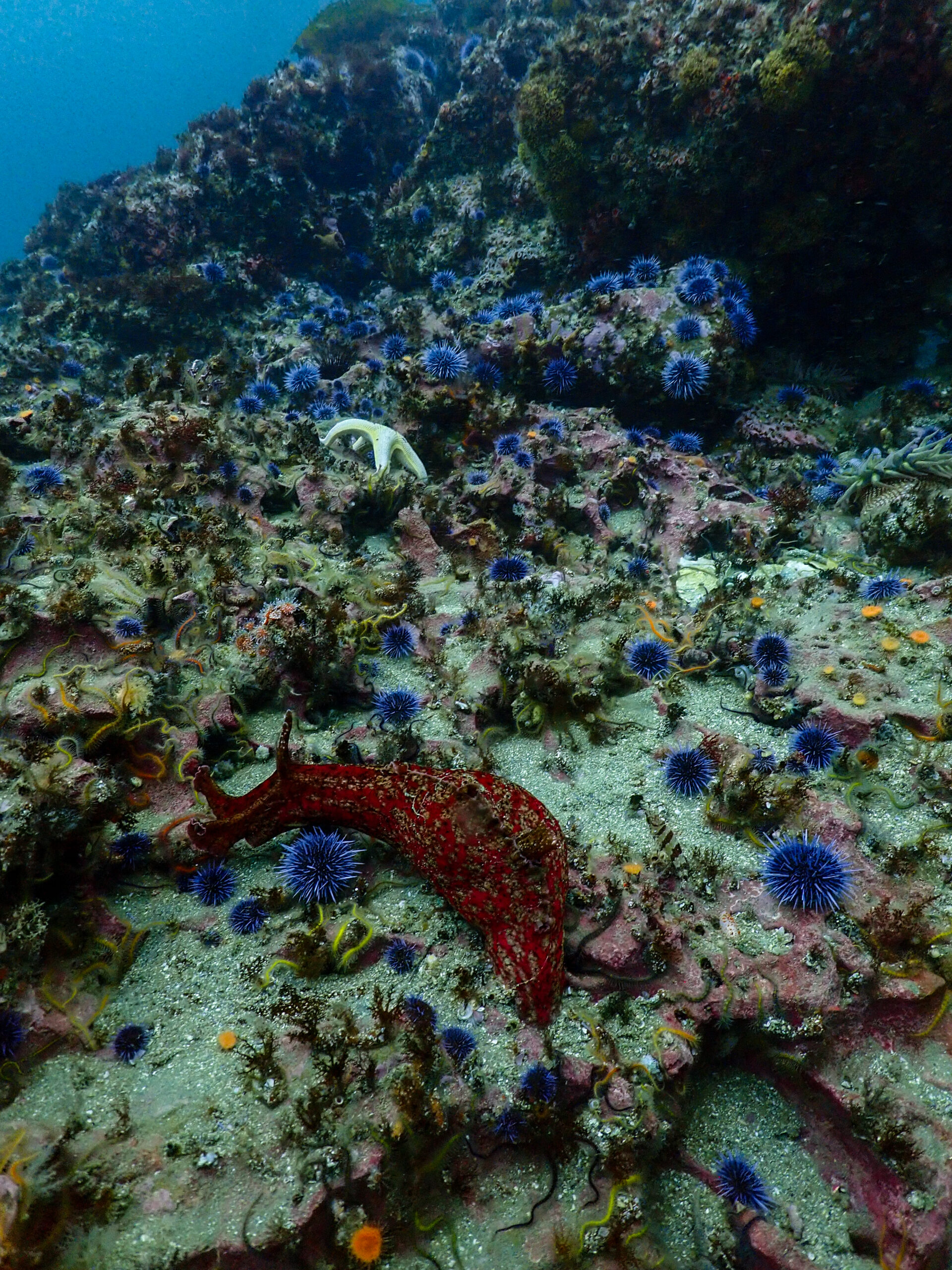

Sea otters were eradicated from the Channel Islands long before the park existed, but since the inception of the park, data has shown the population of abalone, rockfish, and spiny lobsters declining dramatically from overfishing. More recently, sunflower stars have all but disappeared from California due to sea star wasting syndrome. The loss of these species has a cascading effect on the whole ecosystem, disrupting the balance. All of this can be seen from the data collected by the Kelp Forest Monitoring crew over the last few decades. One of the most significant changes is the boom in purple sea urchin populations because of the loss of keystone predators like sea otters, sunflower stars, lobsters, and California sheephead. The out-of-check populations of urchins can overgraze a kelp forest easily, leading to urchin barren sites with relatively low species diversity and low biomass.

I mention all of this just to prove how important a long-term monitoring dataset can be. Using data from the parks, California closed the commercial abalone fishery in 1997. Information collected by KFM was instrumental in establishing marine reserves in 2003, placing nearly 20% of park waters into state marine protected areas thus granting complete protection from fishing and extractive activities. A 2008 review of data demonstrated positive trends in these new marine reserves including greater overall biomass and larger body size of species like the spiny lobster. All goes to show that data is needed to hold humans accountable for our out-of-proportion impact on the planet and our obligation to protect the places we have set aside as national parks.

I’ve come a few days early to Ventura so Kelly Moore was kind enough to set me up to stay with Dave Begun, a retired NPS ranger and diver for the live dive program at Channel Islands. Dave gives me a full tour of the area with bike rides to tacos, a trip to Santa Barbara, and a cruise on Island Packers out to Anacapa, one of the Channel Islands. Before the Anacapa trip though, I get a couple of days of office time with the KFM crew to meet everyone and study up on the many survey protocols.

I head to Ventura Harbor to meet up with Dr. Scott Gabara, marine ecologist for KFM. Super easy-going and friendly, he welcomes me to the team and introduces me to Katie Mills-Orcutt, Ean Eberhard, and Emalia Partlow. Two of their regular divers are out this week so it’s a good week for me to be here to help. The office atmosphere is relaxed and good-natured. I can immediately tell what a solid crew they have. Especially since it’s the end of a hard 6-month field season and the jokes are still flying.

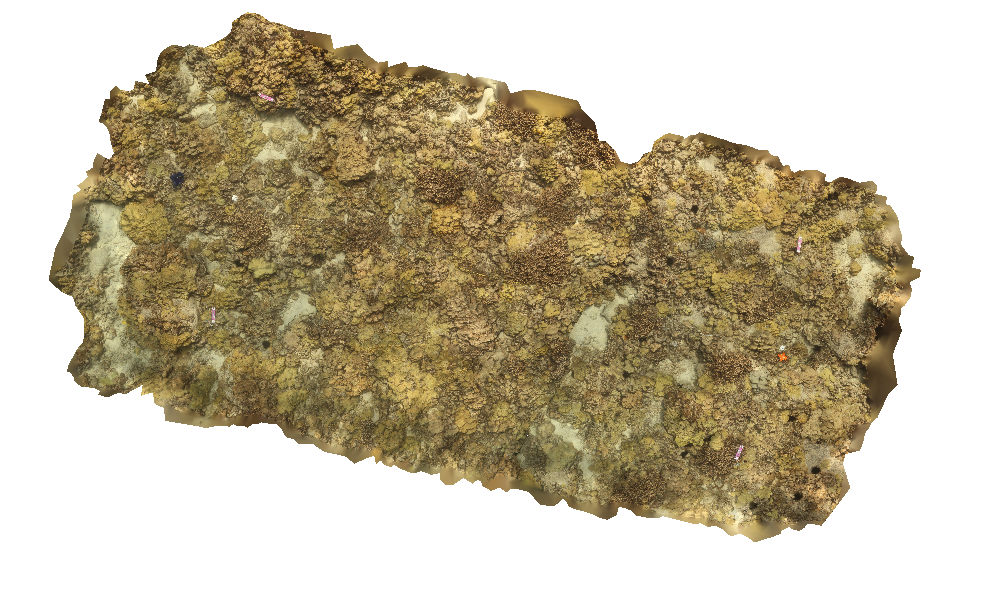

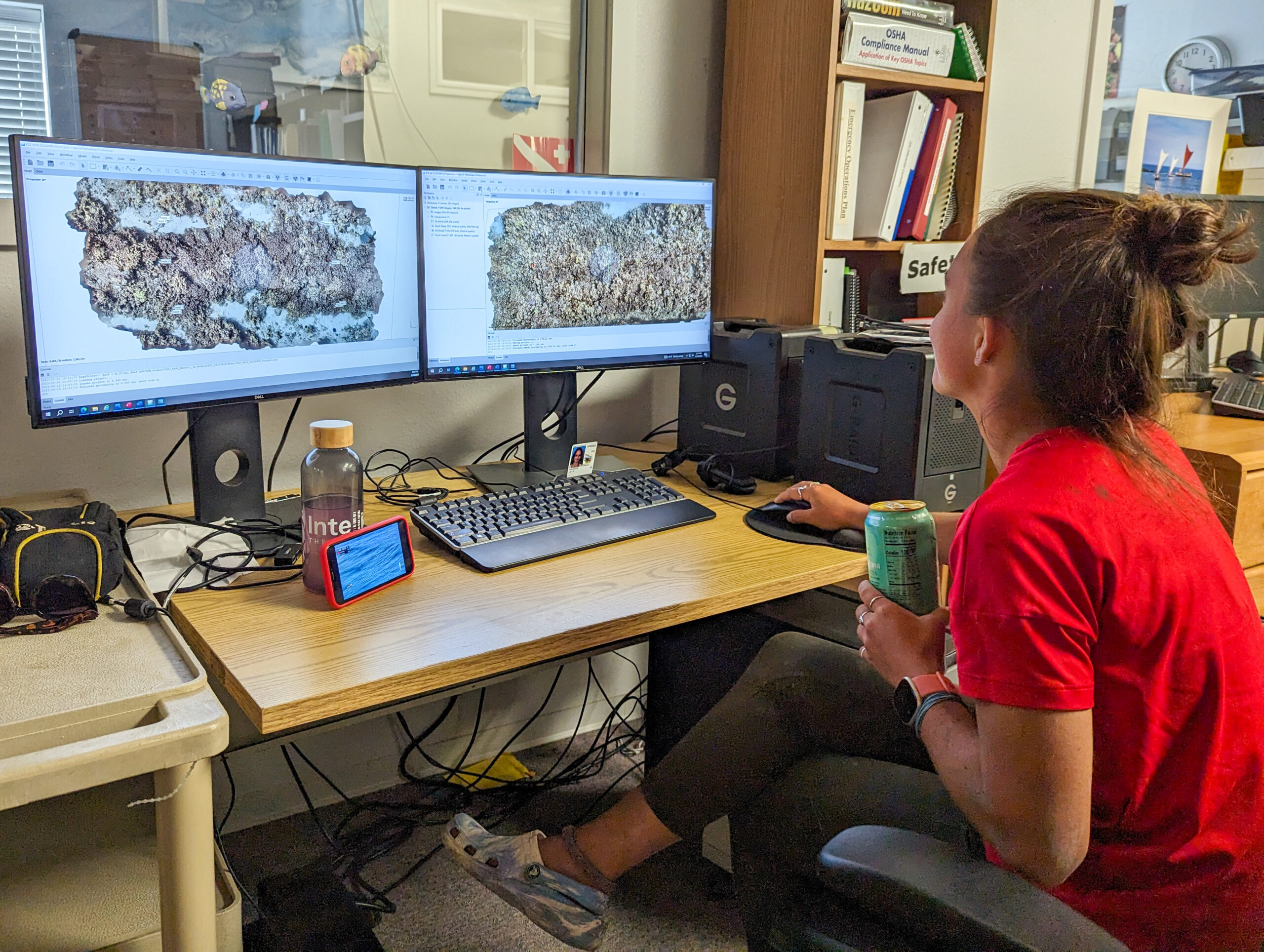

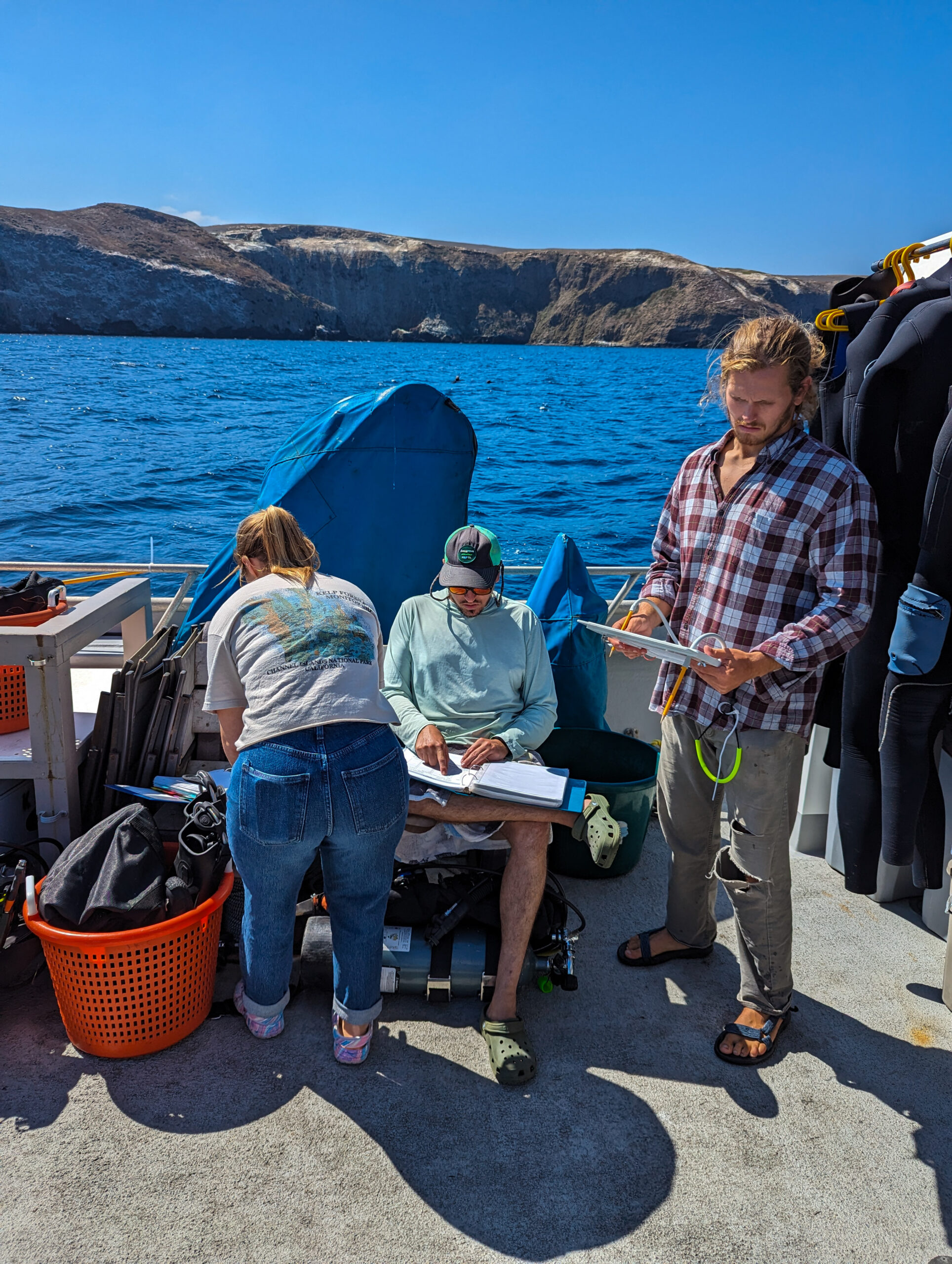

The kelp cruise starts on Monday, so I have a few days in the office to learn as many Channel Island species as possible and get an idea of how the protocols work. I can tell you this will be some of the most comprehensive surveying I’ve ever been a part of. The team collects large amounts of data at each of their 33 sites to get a full picture of the subtidal community structure and dynamics. The sites are large, 100-meter transects. Many dives are required to collect all of the information. They collect size and abundance data for 70 categories of algae, invertebrates, and fish that are indicators of ecosystem health. While I’m reading up on the protocols, the rest of the team is entering their last week’s cruise data into the database. Data recording is thorough with transcriptions double, triple, and quadruple checked for accuracy. One last task is provisioning for the week and I join Emalia on Friday to hit up Trader Joe’s.

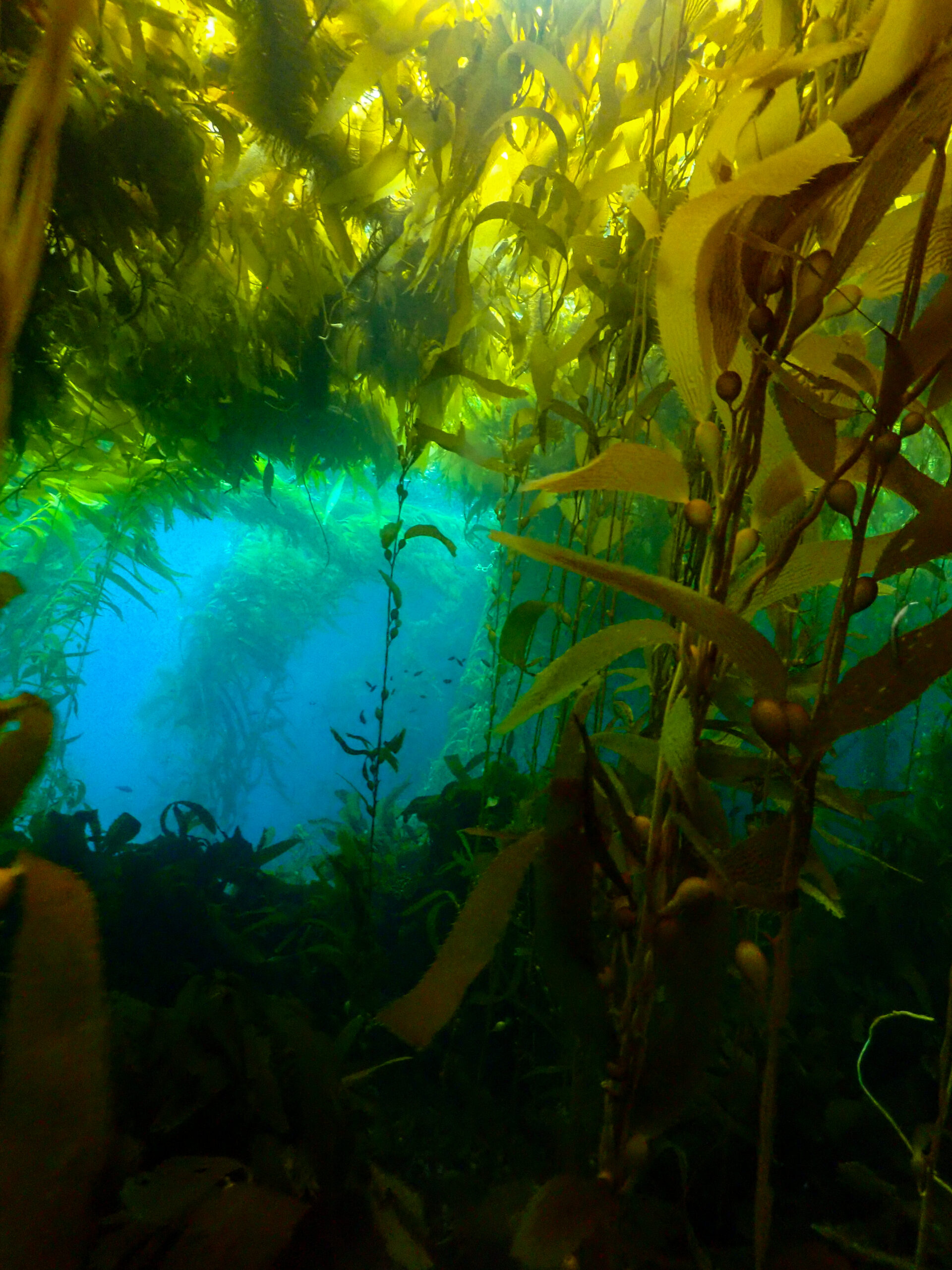

Over the weekend Dave and I go out to Anacapa. It’s a foggy day and a 12-mile journey on Island Packers out to the closest of the Channel Islands, through the Santa Barbara channel and past the oil rigs. Finally, the small volcanic island of Anacapa comes into view, tall cliffs lined with brown pelicans looking down on us. The boat pulls into the landing cove, full of Macrocystis pyrifera (Giant Kelp). I love comparing the different ocean colors of my internship, the bright sky blue of the Caribbean, the deep royal blue of Hawaii, and now the emerald green of Southern California.

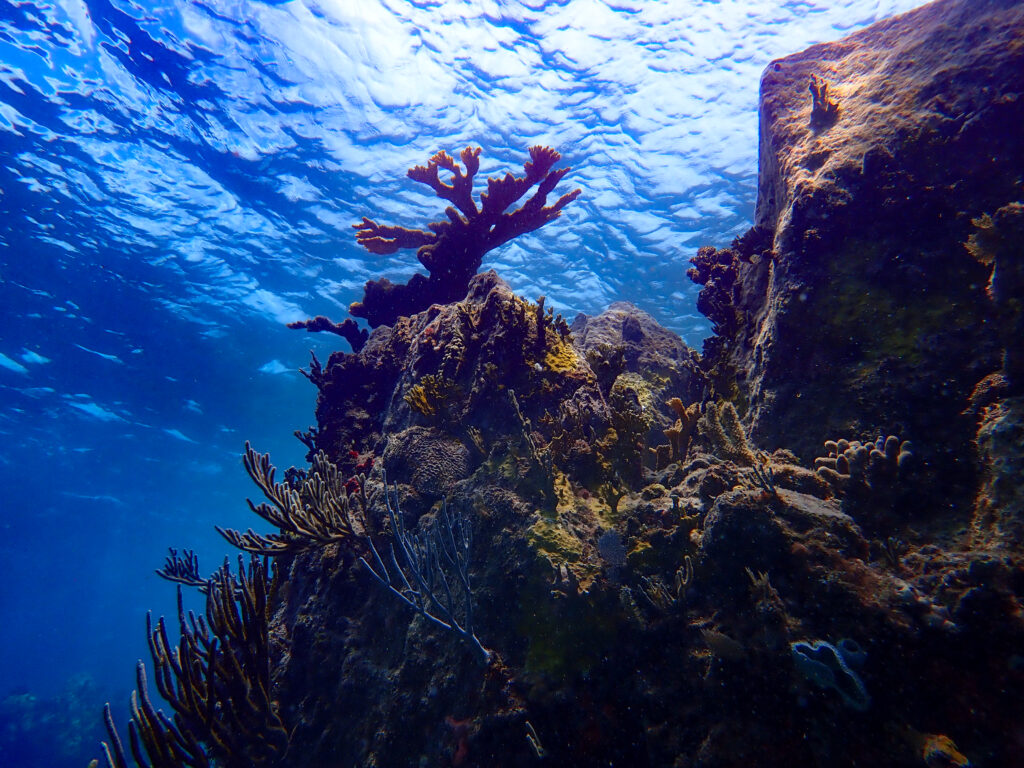

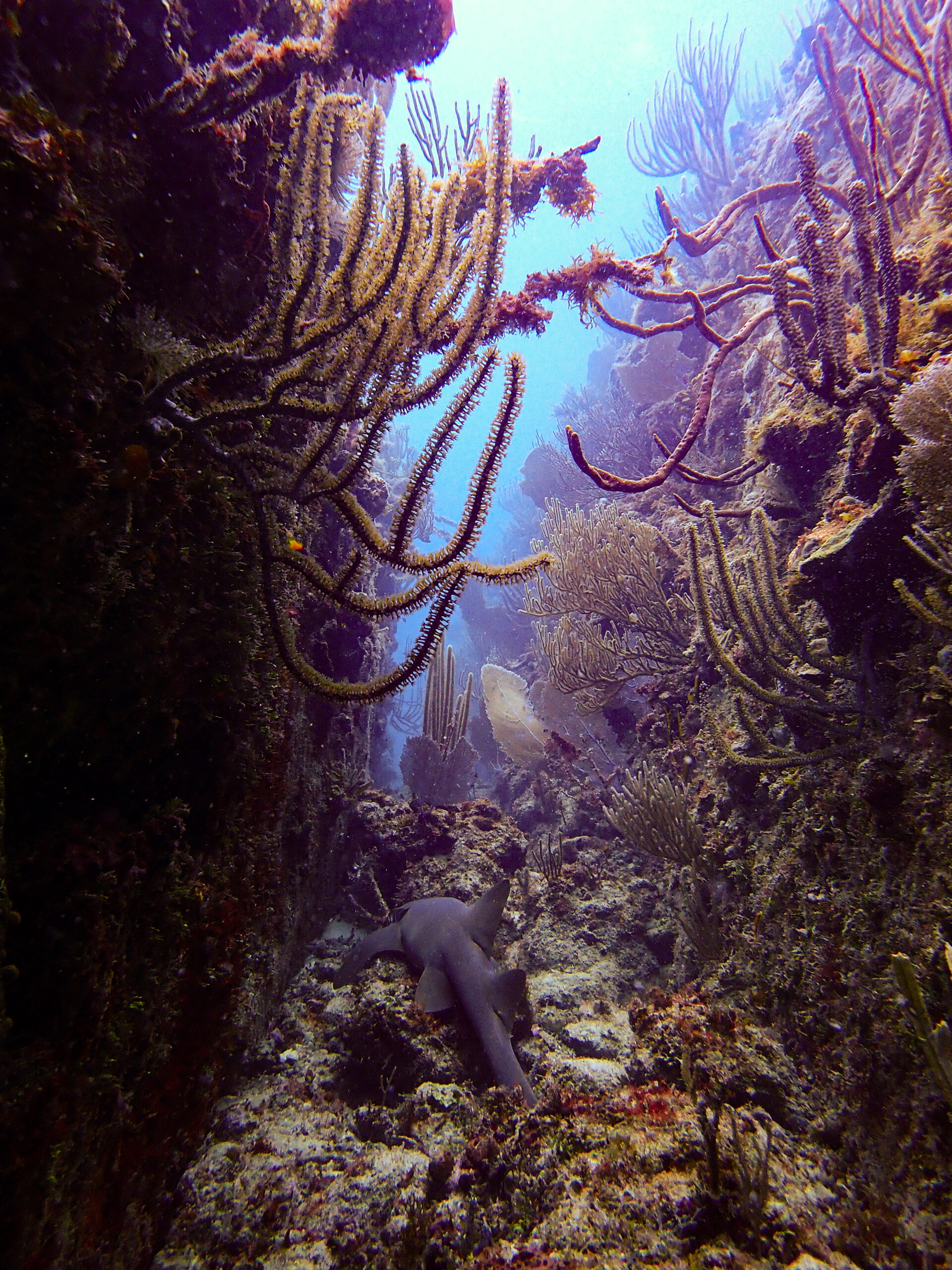

The fog horn blares continuously as I wander the small island, watching the sea lions body surf far below. Dave told me to bring my snorkel gear, so I hop in the water at the landing cove as soon as I finish my hike and am immediately mesmerized by the undersea jungle. A thick canopy of kelp blots out most of the sunlight, only letting streaming light beams down through the crystal-clear water. Little fish hide within the vertical foliage, the rocky bottom is made up of dark brown Laminarian macroalgae, bright green surfgrass, and red algae. I see my first bright orange Garibaldi. The water temperature isn’t as bad as I thought it would be. I could stay in here for hours but the boat is coming back to pick us up. One last treat on our journey back. Right off of Anacapa, we come across a massive school of bluefin tuna feeding. I’ve never seen anything like it, streamlined torpedoes breaking the surface almost too quickly to see. The charter boat captain says in their 40 years of coming out here they’ve never seen this before. Maybe it has something to do with this year’s El Niño bringing in warm water.

It’s Monday and the kelp cruise starts today. Unfortunately, I never sourced a drysuit or 7mm so I’m just working with my 5mm and Scott’s extra 7 mm jacket. As we are loading up the boat in the morning, I meet Keith Duran, the captain of the 58-foot Sea Ranger II where we will be living for the next five days. Frankie Puerzer, a diver from a lab at UCSB has also joined for the week.

Being at the mercy of the weather means that the dive schedule isn’t finalized until the day of the cruise. The season is from May through October and some of the more difficult sites are left just because the weather hasn’t cooperated. However, this week is looking relatively calm and we should be able to dive some of the southern exposed sites. We will start with a relatively close site off of Anacapa for our half-day today.

The trip out is sunny and calm and we are visited by some bowriding dolphins. I can hear their high-pitched vocalizations. We talk about the plan in the cabin, but I’m easily distracted by the dolphins I can see out the windows jumping on either side of the boat. Our first site is going to be Black Sea Bass Reef off of middle Anacapa. The birds are going crazy right now. Pelicans are diving like mad.

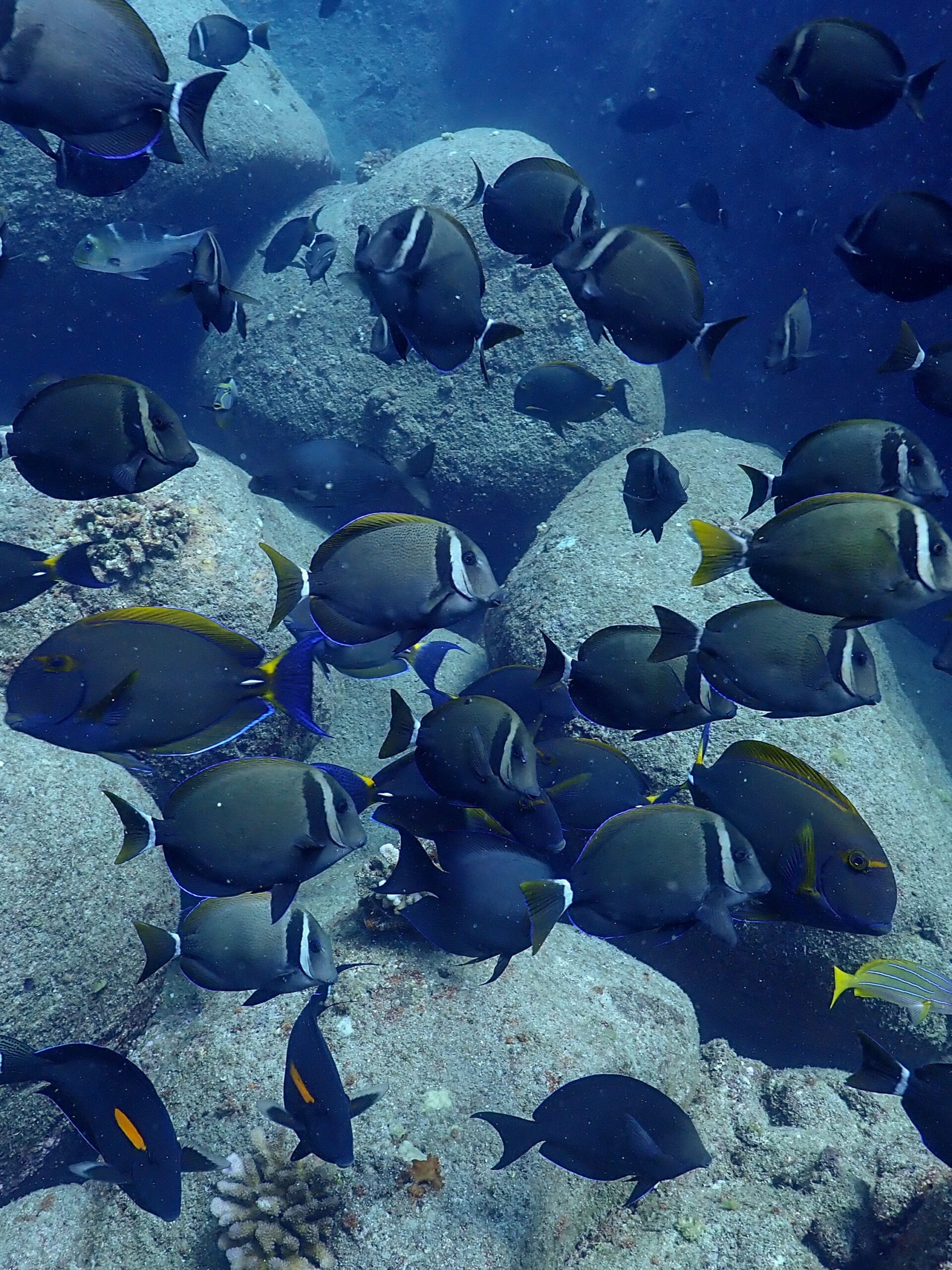

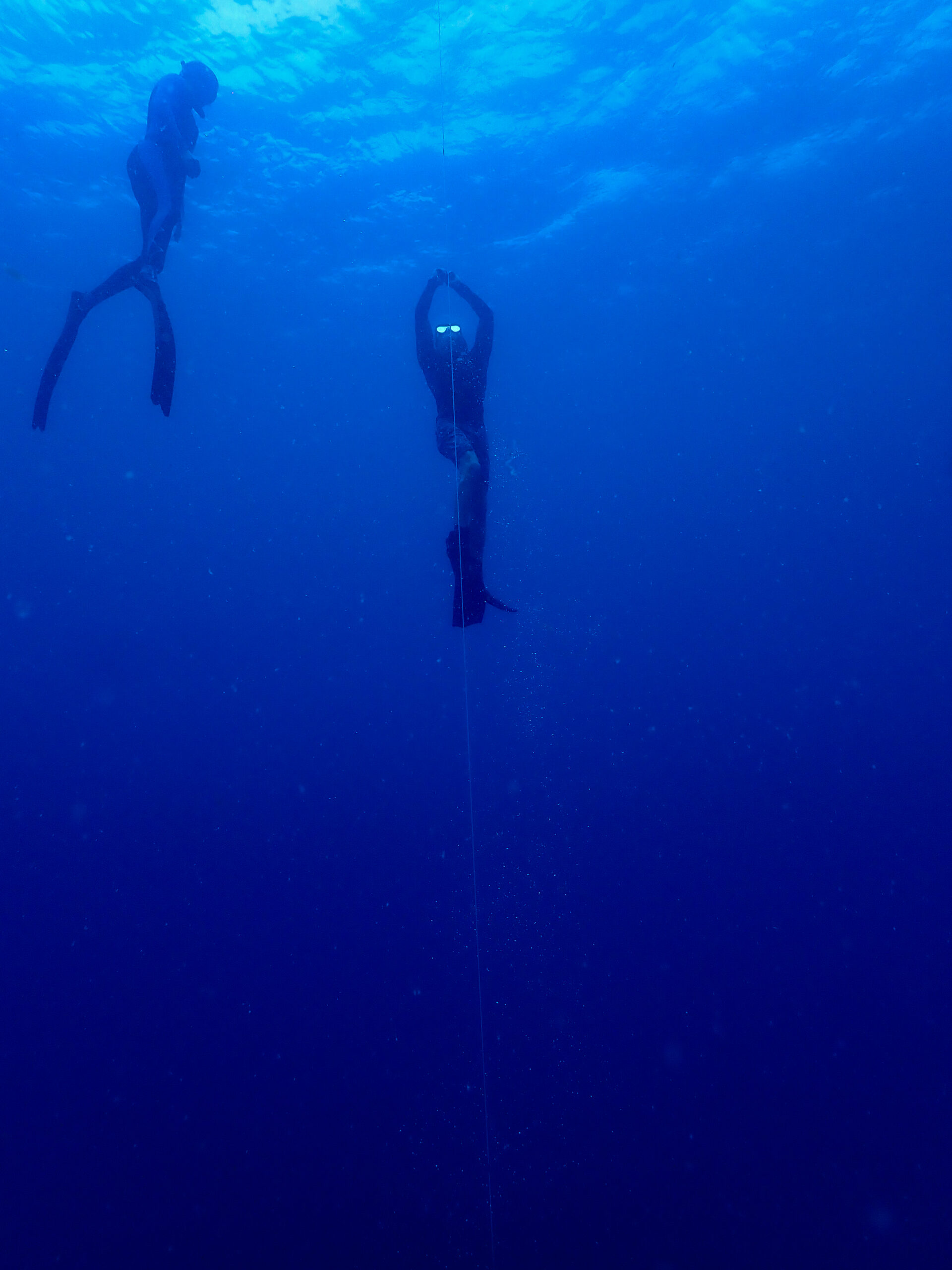

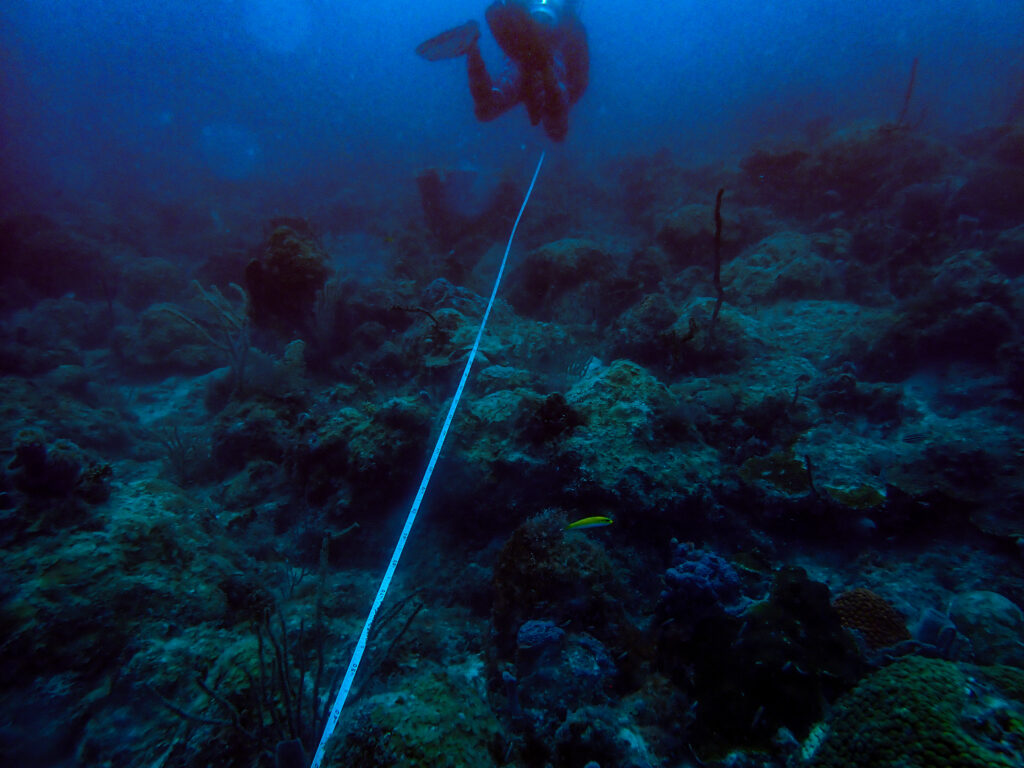

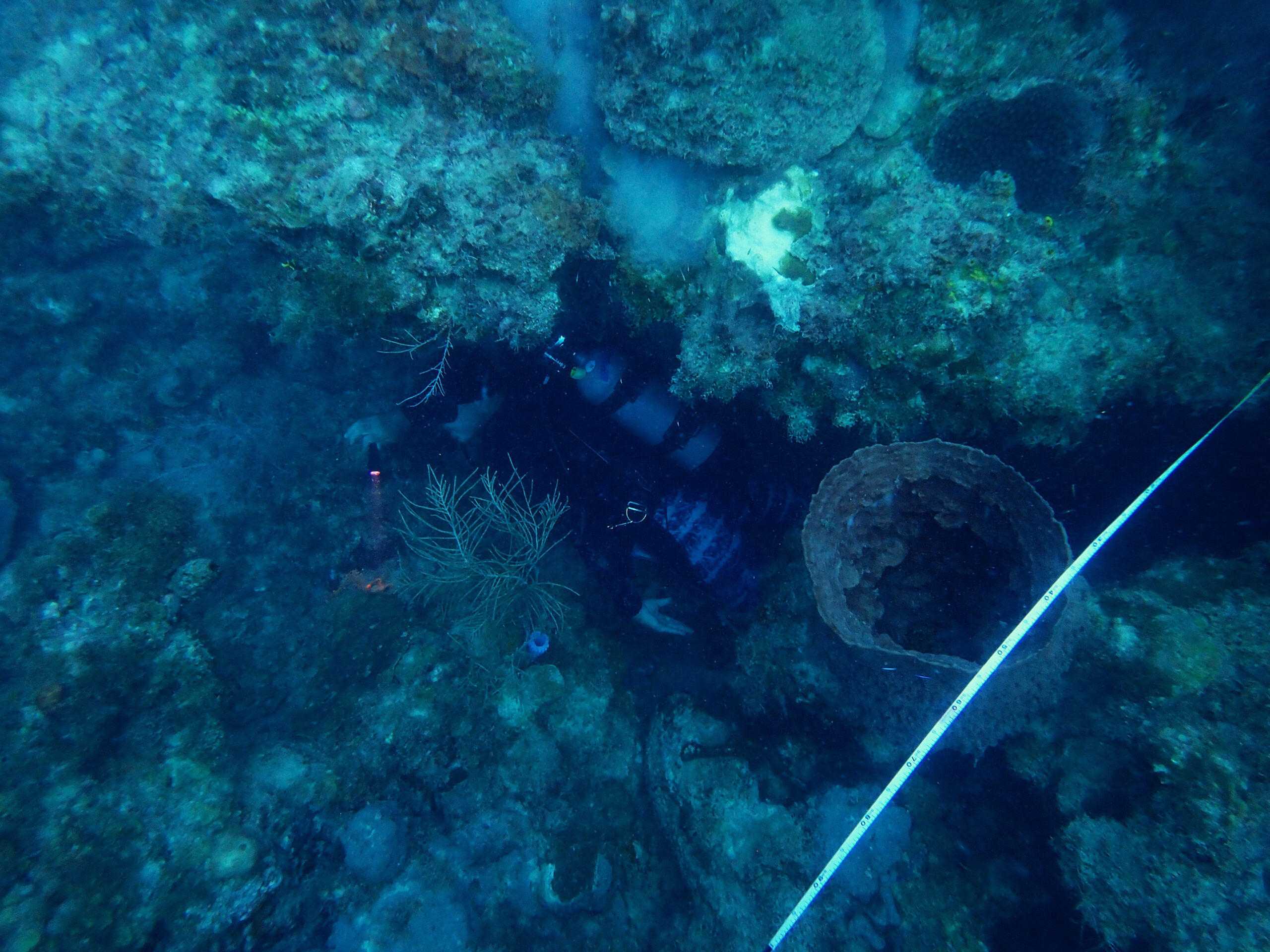

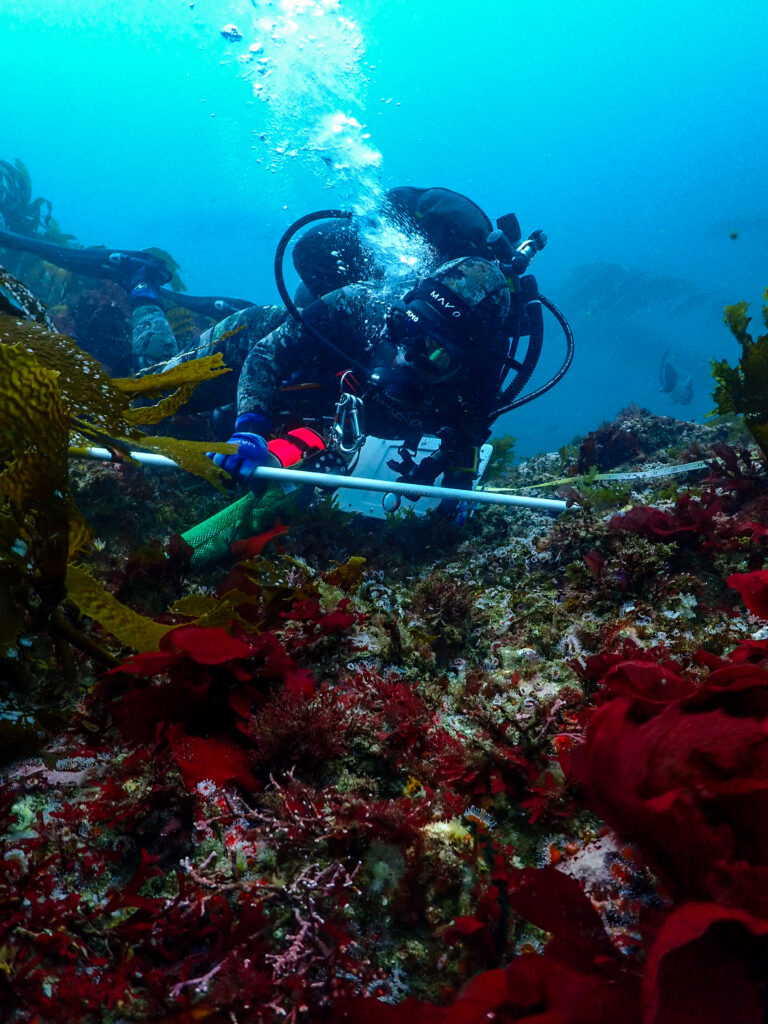

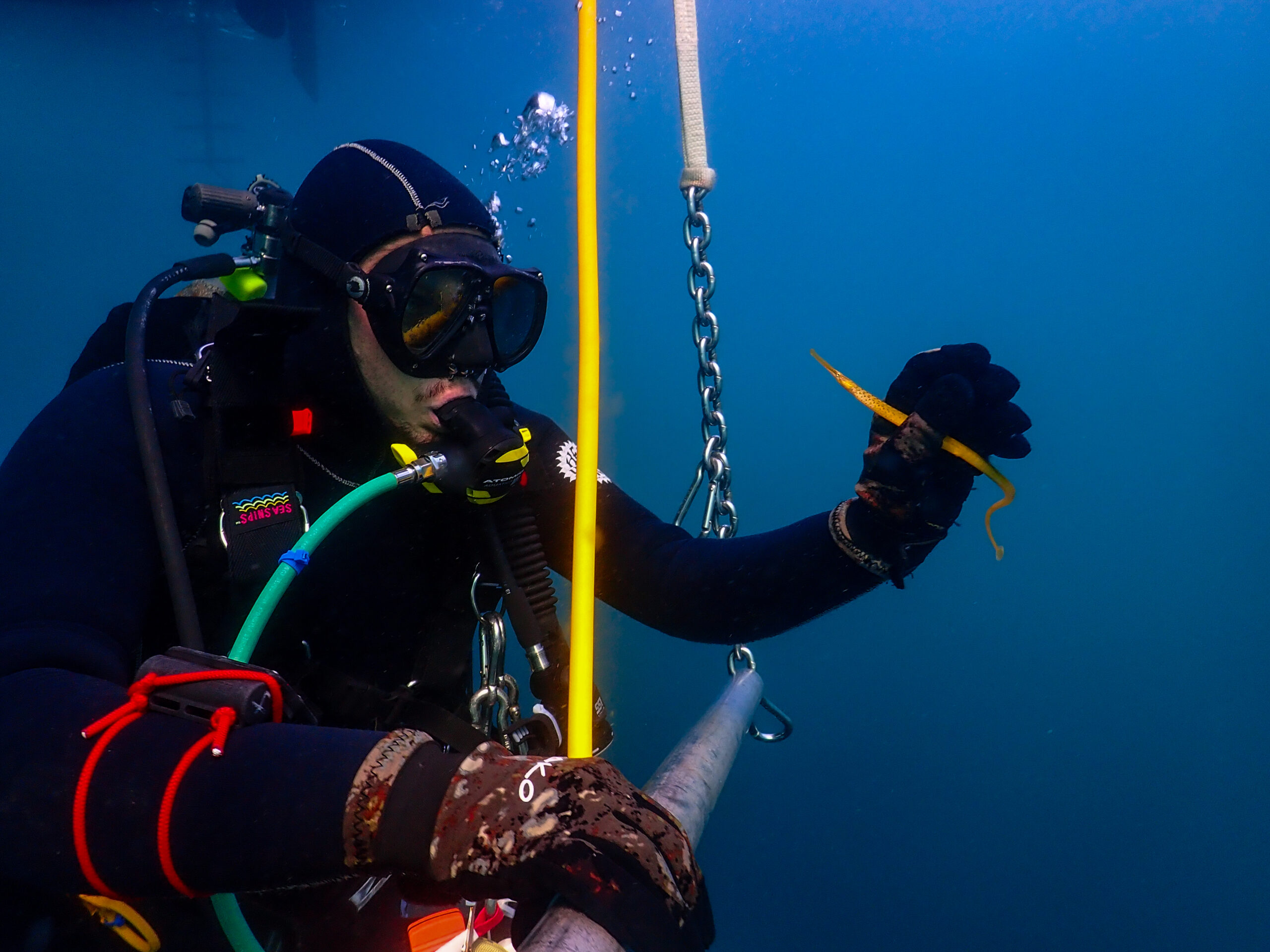

Keith and the team are a well-oiled machine. They set the bow anchor and stern anchor so we are situated near the middle of the transect. Scotty and Katie slather up their 7mm wetsuits in mane and tail and jump in to locate the fixed lead line marking the site, run the 100-meter transect, and do the video recording. I’m shadowing Ean today while Emalia and Frankie are doing the same protocols, just on the opposing side of the transect. Our first dive is a roving diver fish count survey. This is a method for estimating fish species density, abundance, and diversity. I find it quite ambitious because we’re surveying the entire water column of 2000 square meters in 30 minutes, identifying and counting all fish we see. We jump in and I am overwhelmed by fish. Ean is pointing out as many as he can. Senorita, blacksmith, kelp bass, kelp perch, sheephead, and opal eye. On the bottom, black-eyed gobies and island kelpfish. Bat rays cruise past large white sea bass in the distance. I love it because it’s like a mix of cold-water WA species with a smattering of brightly colored warmer-water species like Garibaldi. Unfortunately, I did not see the black sea bass. Not much Macrocystis but the bottom is blanketed in Laminaria. We finish the dive with the 5-meter quadrat surveys which are density estimates for species like Macrocystis, Pisaster giganeteus (giant sea star), and Pisaster ochraceus (ochre sea star). All dives finish off with a 15-foot safety stop at the oxygen bar where regulators are set up to breathe 100% oxygen. A good way to stay fresh throughout the long dive week.

Next dive, I’m shadowing Ean again on a different protocol. Band transects are the main protocol for estimating densities for many of the invertebrates that KFM monitors. 12 bands on each side of the 100-meter transect. A 3-meter band, 10 meters out from the main transect. Emalia is on the other side doing the same thing. It’s taking a long time to check under all of the Laminaria. Ean is looking for abalone, giant keyhole limpets, sea stars, urchins, gorgonians, lobsters, orange puffball sponges, and scallops. Ean is finding the occasional Kelletia whelk to measure. We only finish 3 bands. On the surface, the waves are getting rough and the sun is going down. A quick change of plan, not enough time to finish the site today so we’ll scrap the bands and do them another day. One more dive and my job is to count all the stipes of the giant kelp in my half of the 100-meter site. Frankie points out a colorful juvenile treefish and we find a horn shark wedged between a rock. The dive finishes and we motor through the waves and setting sun over to Smuggler’s Cove on Santa Cruz where we will anchor for the night. Katie makes quiche for dinner and we have a full spread of ice cream options for dessert. Lights off at 9.

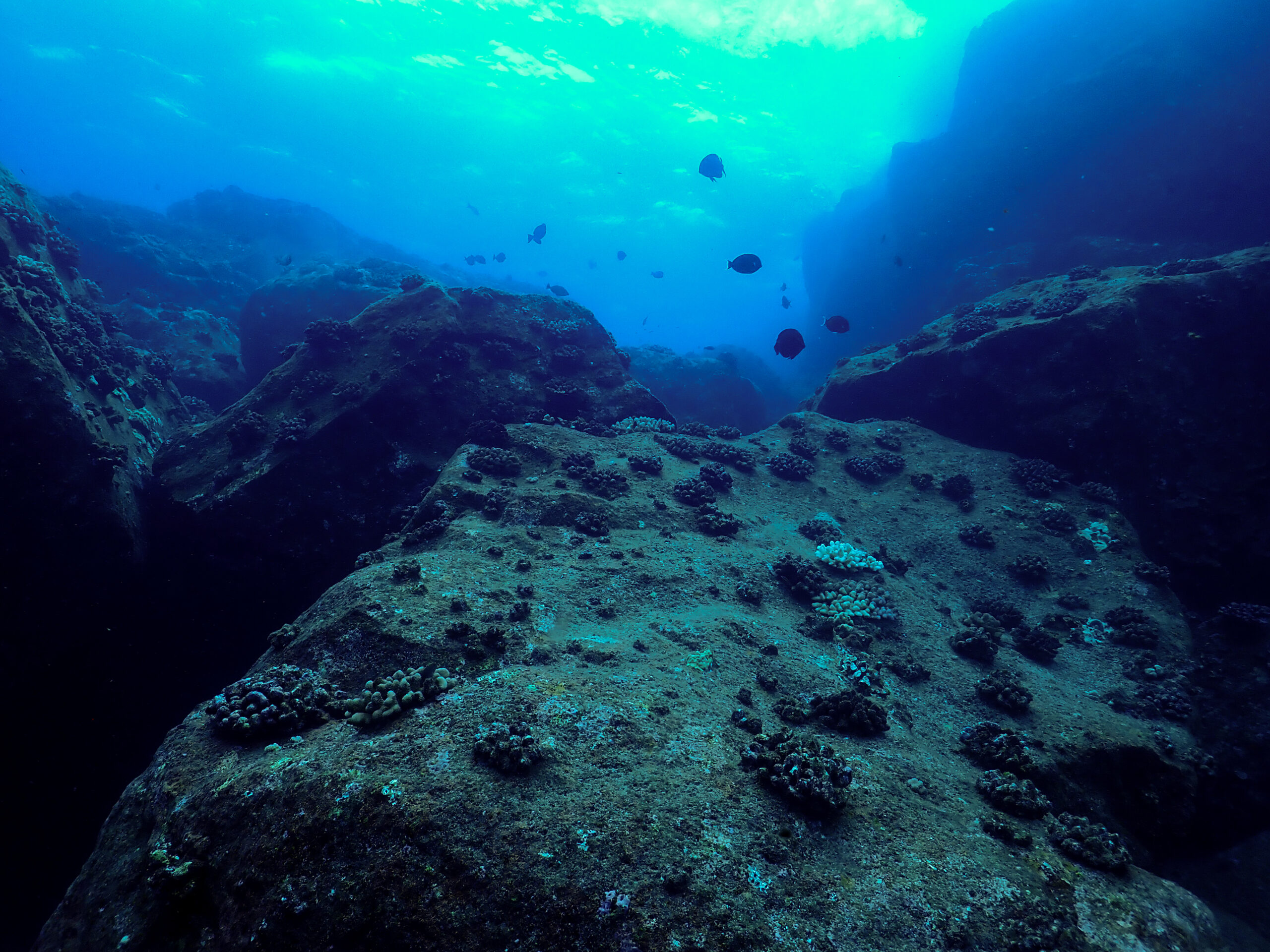

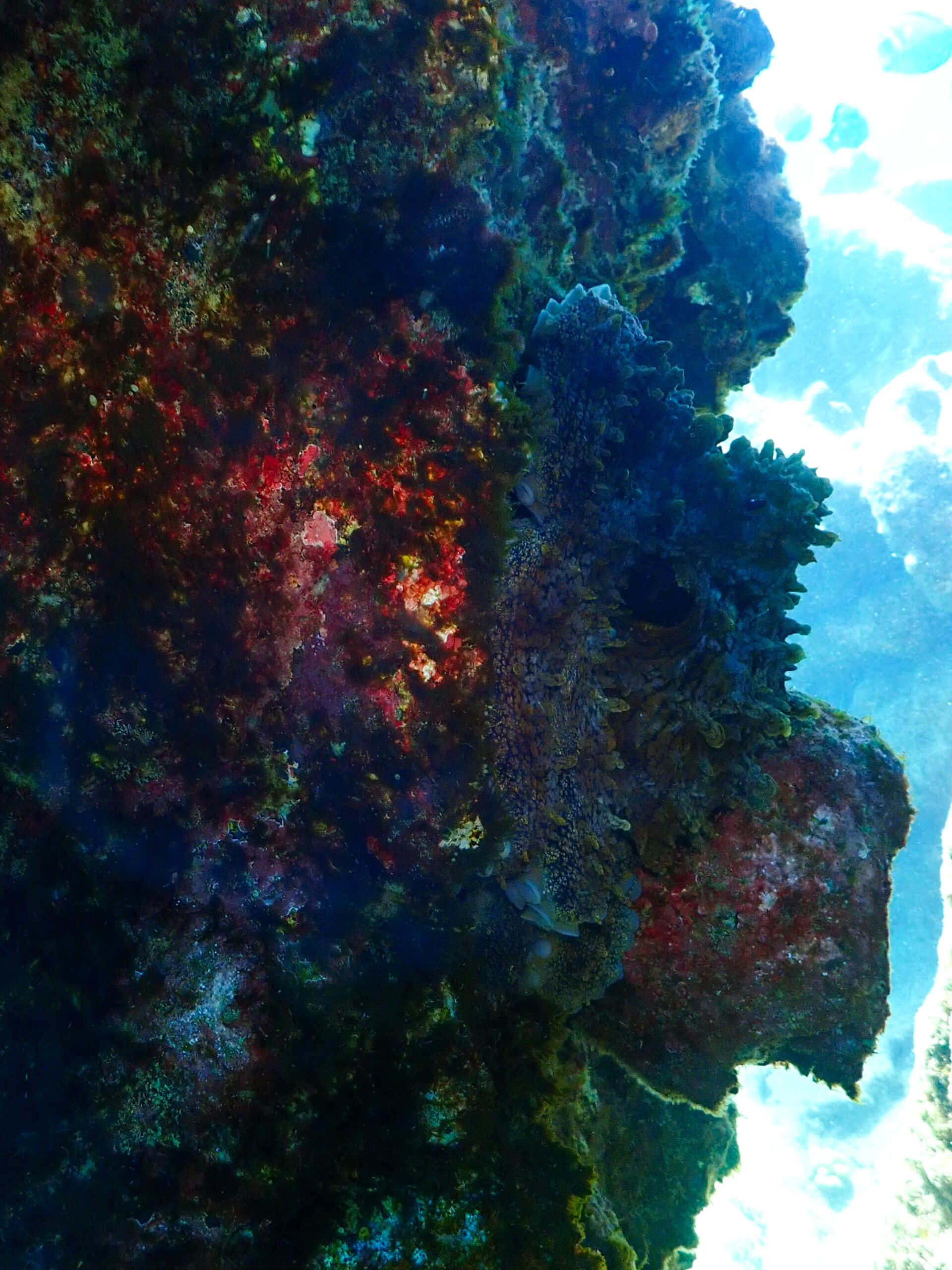

We have a long motor this morning as we cruise all the way to Santa Rosa Island along the south side of the very long Santa Cruz Island. We make it to Johnson’s Lee South but the current looks like it’s ripping, so we give it a couple hours to calm down. Male elephant seals battle on the beach. We get some late afternoon diving in. I dive with Ean and we start with roving diving fish count surveys again. A lot of blue rockfish and other rockfish species this time. This site is stunning but very different from the last one. First off, it’s much colder, 55 degrees as compared to 65 at Anacapa yesterday. The colors are beautiful, tons of purple sea urchins, bat stars, anemones, and brittle stars waving their little arms in the current.

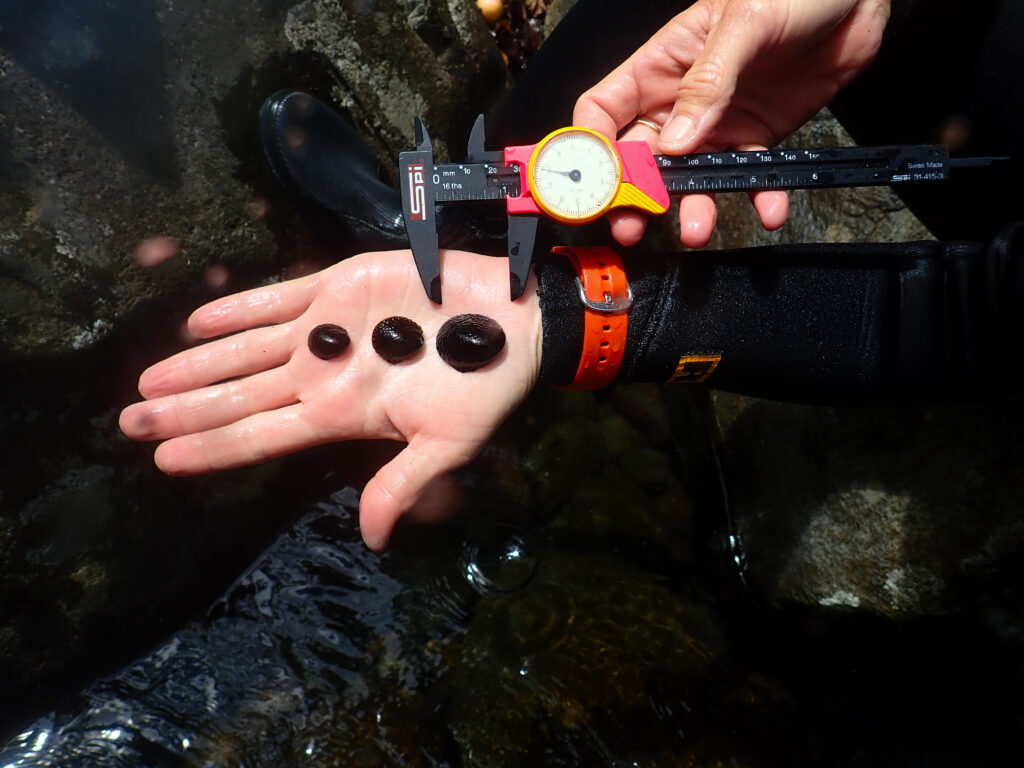

After counting fish, I am searching for and measuring rock scallops and bat stars as part of the natural habitat size frequency distribution surveys. The aim of these surveys is to quantify the size frequency distribution of certain invertebrates. The measurements can be used to calculate biomass, and detect differences between islands or even inside and outside of marine protected areas. For most invertebrates, we are trying to get 60 individuals at a site, so I’m searching for 30 scallops and 30 bat stars, and the other diver on the other side of the transect will get another 30 of each. On the next dive, I’m measuring Kelletia whelks. I see Spanish shawl sea slugs, giant keyhole limpets, orange puffball sponges, fields of anemones and so many big sea hares! That’s it for today, current is picking up again and we barely make it back to the O2 bar. Emalia makes sushi bowls for dinner and I stuff my face. We anchor closer to shore.

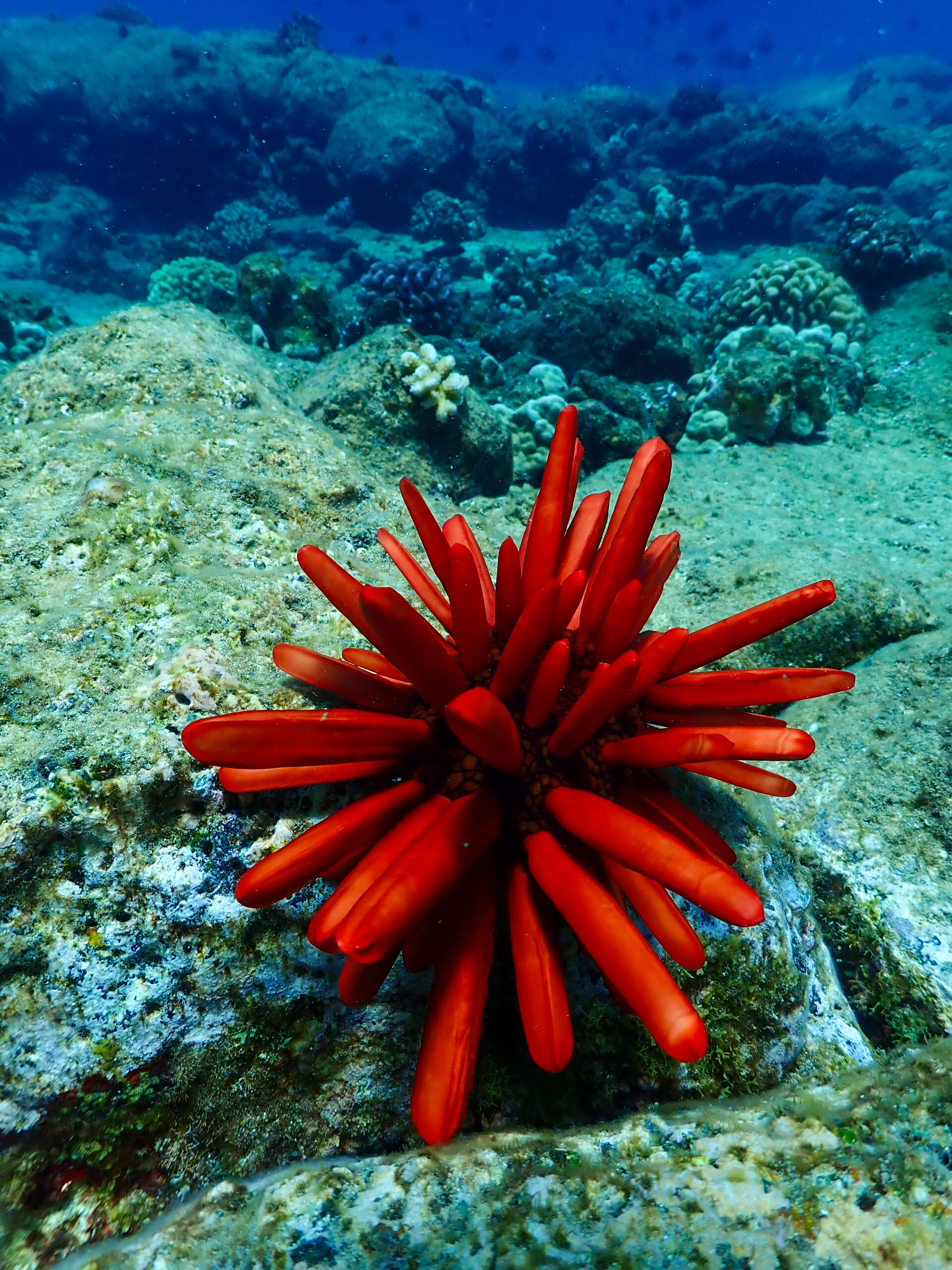

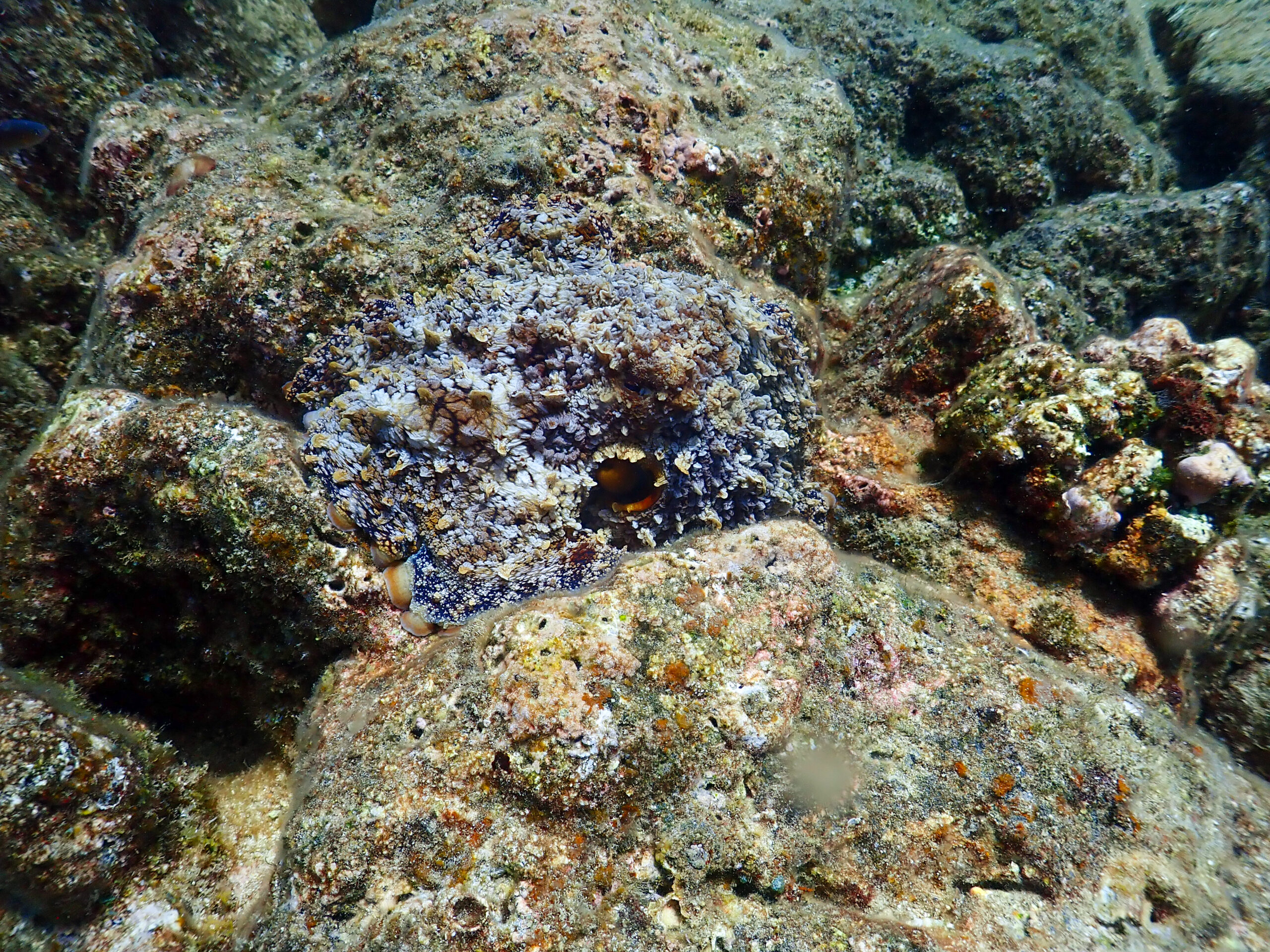

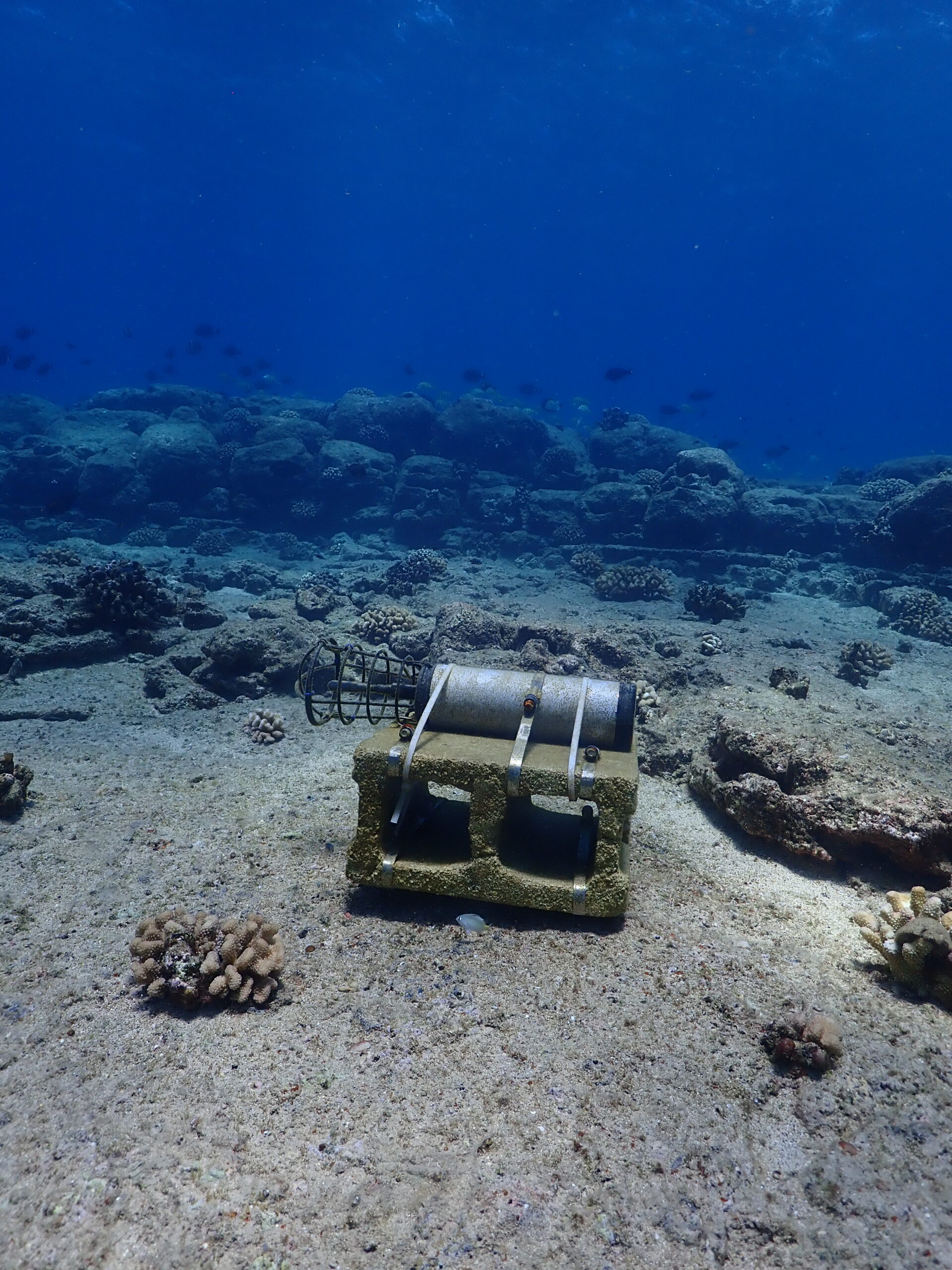

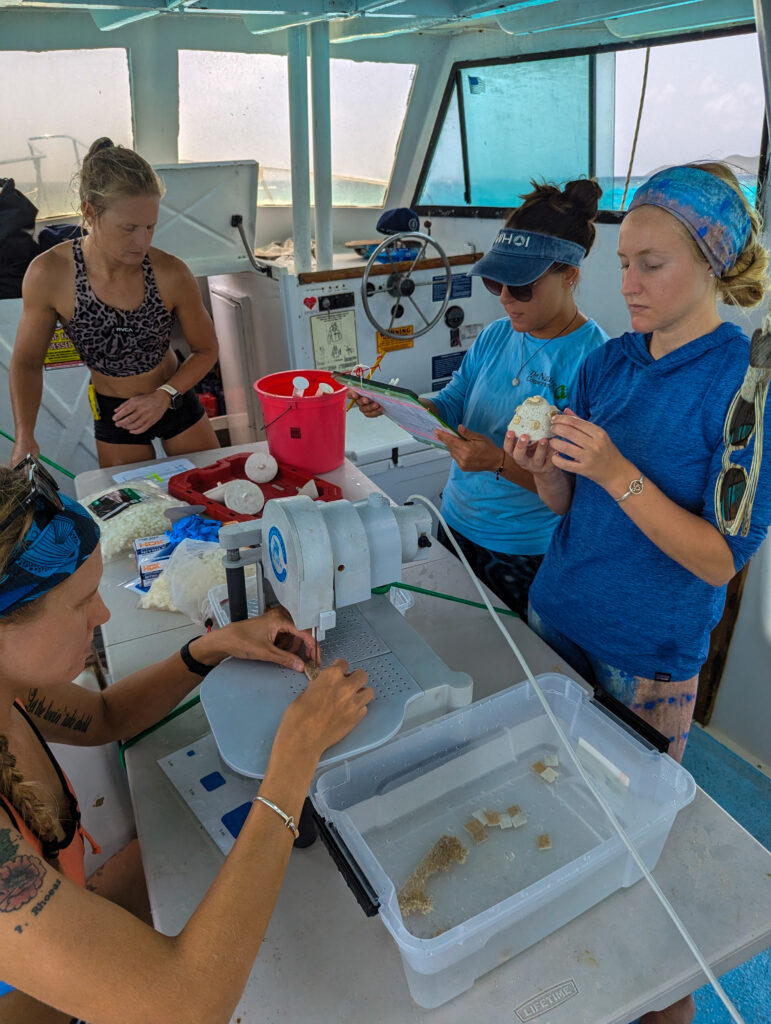

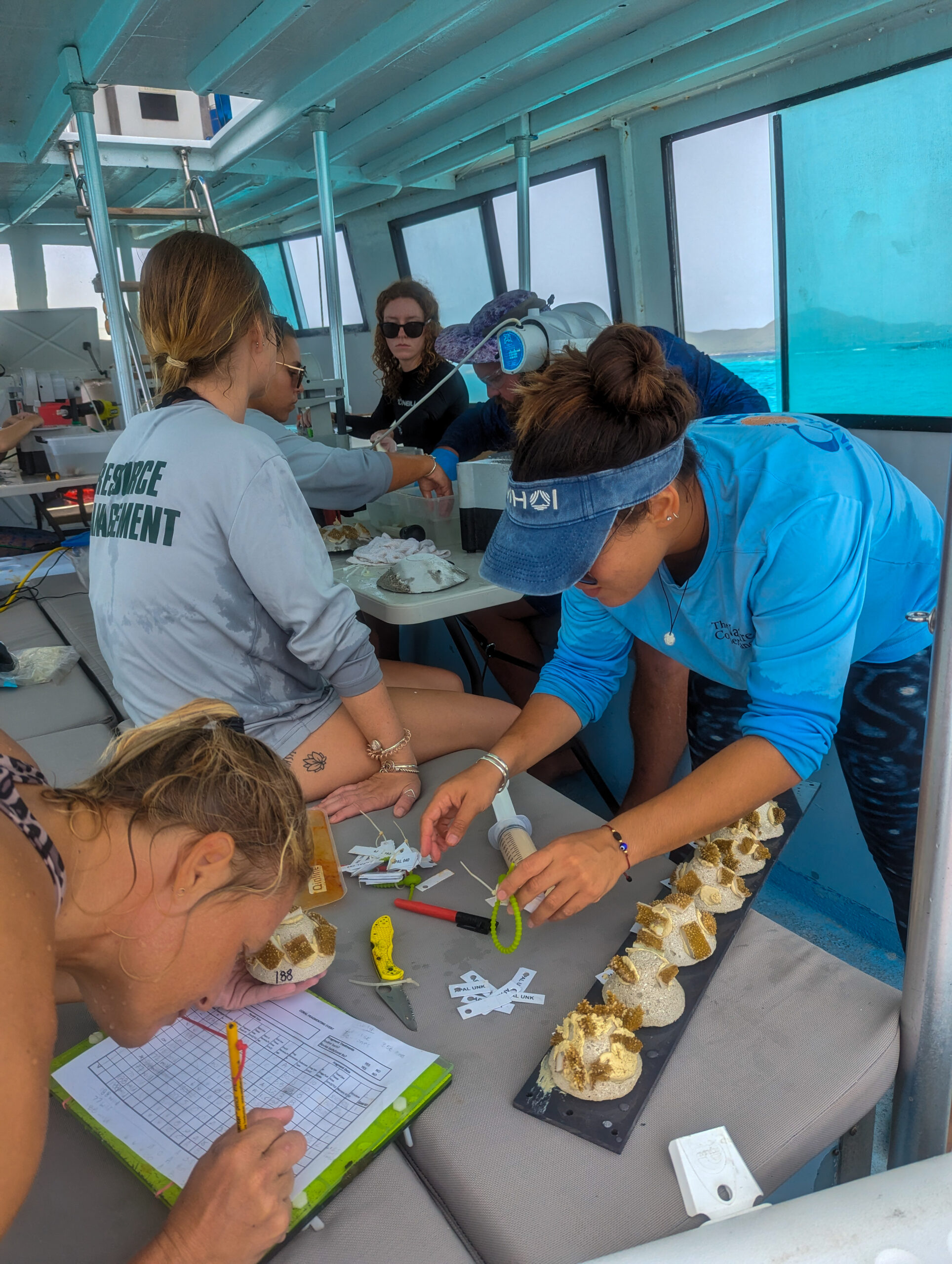

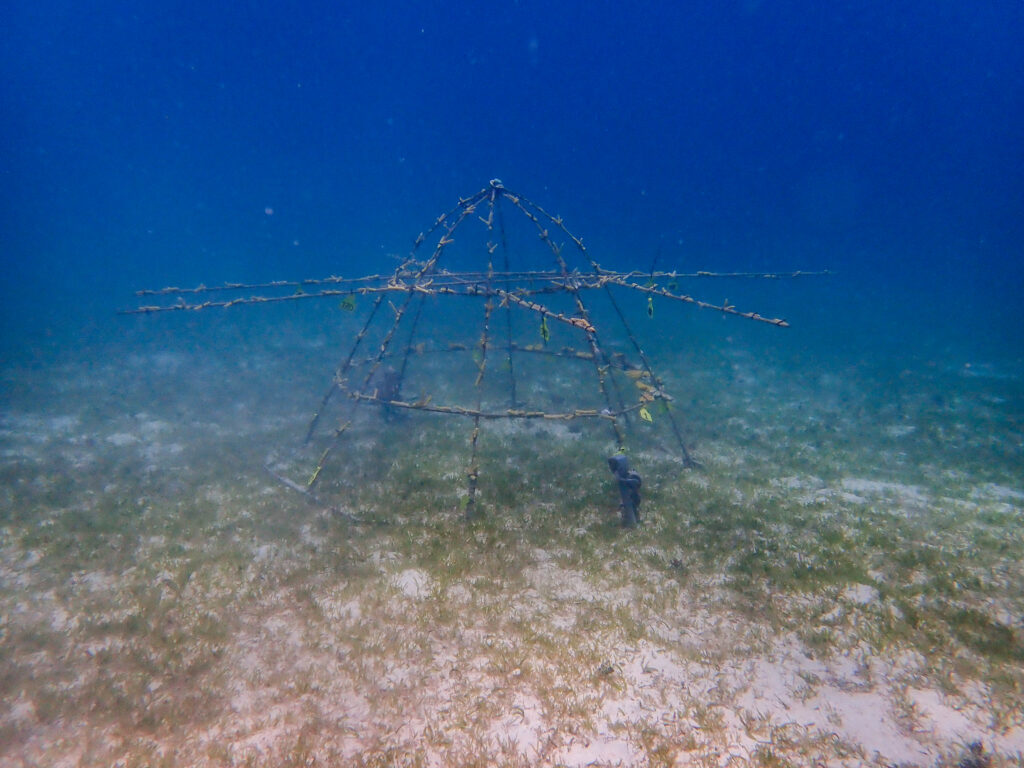

In the morning we finish Johnson’s Lee South. I’m diving with Katie today. As she does bands, I’m collecting 100 red sea urchins in my mesh bag of the 200 needed for the natural habitat size frequency distribution. It’s more efficient to measure 100 urchins on the deck during the surface interval rather than underwater. I’m also measuring any Pisaster giganteus and counting Macrocystis stipes on the offshore side of the transect. The sea lions have come to play and they twirl around us gracefully, occasionally startling me when I see one hurtling towards me out of the corner of my eye before it banks away. I am very impressed by the amount of data that the crew collects and the number of species that they need to know. I’ve only mentioned a few of the protocols that I’ve been helping with but there are many more including artificial recruitment modules which are used to assess recruitment of invertebrates. Basically, a tool to see what organisms and how many have moved into an artificial habitat that is created at a site with a cage and bricks. The crew already completed the counts for the artificial recruitment modules at this site on a different dive week.

On the surface, I flush my wetsuit with the hot water hose and top my tank off with the air compressor. I dump my mesh bag of urchins into a bucket and grab calipers to measure them all. On the next dive, I have to collect some more red urchins to hit my 100 count and some white urchins to finish all of the natural habitat measurements. The sea lions are still swimming around but the current is getting much stronger. We finally finish all of the protocols and the site is complete. Back on the boat, with snacks and tea, we sit in the cabin and do one last species list, ranking the prevalence of every single species present at the site. We also double-check the data sheets. Since we can’t do any other sites today we chill out and eat snacks in the sun on the back deck. I make a red curry for dinner in the little galley.

It’s Thursday and we’re heading to Gull Island today off of Santa Cruz. I’m excited because the other site option was an urchin barren. Gull Island is a complex kelp forest and sounds much more interesting to dive. Obviously, it’s important to get data from urchin barren sites as well as kelp forest sites to see the massive differences but selfishly I want to dive the kelp forest because I know it’s going to be stunning. I’m diving with Scotty. First dive, he is doing 5-meter quadrats inshore while I’m counting stipes and measuring Crassadoma (rock scallops). There is so much Macrocystis, the site is dark and rugose. I easily get my 100 kelp counts and I watch Ean get surrounded by sheephead trying to eat the urchins he is collecting. I finish my scallop measurements and help Scotty finish his Megastraea undosa (wavy turban snail) measurements. I still haven’t seen an abalone, and the others have only found a few. I do get to see Stylaster californicus, a purple hydrocoral, usually found in deeper colder water. This is one place you can find it shallow in the Channel Islands. So cool. On the surface, I eat Scandinavian swimmers (gummy candy) and get covered in kelp flies. I dictate data to Katie who records it for me.

Next dive, Scotty is doing bands and I’m measuring snails, urchins, gorgonians, and stars. I’m more confident now with my identification so I’m getting some more responsibilities. On our side of the transect, we have a sand channel between the rock outcroppings and in the channel I have the most amazing moment with a harbor seal. Over the course of the dive, the seal repeatedly comes back and boops my camera lens or my mask with their snout. When I’m head down in the kelp, they’ll poke my head until I pay attention to them. The seal glides around so relaxed; it is really special to be face-to-face with this beautiful creature. Meanwhile, sea lions are zipping through the kelp, not being chill at all, but still very graceful.

Another dive looking for the same species to finish up the transect. I don’t find many Tegula snails, red turban snails, or bat stars so I don’t hit my mark of 30 each. Scotty finishes bands and then we reel up the 100 meter tape and attach the lift bag to the stern anchor. The site isn’t finished, there are a couple more protocols that need to be completed but they’ll come back and finish it on the next cruise. We motor back to Smuggler’s Cove for the night. Such a great crew, there are lots of laughs at dinner. Ean makes butternut squash soup.

It’s the last day of the cruise and we’re finishing Black Sea Bass Reef. I’m sad the week is already over. What an amazing ecosystem, and amazing crew. Thank you so much Scott and crew for taking me in and sharing your knowledge and trusting me to help out with your surveys. Kelp Forest Monitoring has been a highlight of my internship.

Thank you Submerged Resources Center and Our World-Underwater Scholarship Society for setting me up with all of the amazing experiences this summer.