After a few sites, Alex and Laura hop in to move some cinder blocks that mark sites. They do this with their fins off and run on the bottom of the ocean with the blocks in hand. It is quite a site and Laura is particularly excited to get some photos of herself running the blocks around. I descend with them. I set up my strobes and turn my camera on. I set my aperture, shutter speed, and ISO, then go to press the trigger. Nothing happens. I check to make sure I have everything set properly and try again. Nothing. I check the battery, which was at ¾ to start the day. It’s dead! I’m shocked, these batteries usually last 3-4 days and this is the second day I’ve used this battery. I’m disappointed that I can’t get any shots of Alex and Laura running with the cinder blocks on the ocean floor and feel like I let them down. I take some GoPro video instead, but it’s certainly not as good.At the St. Croix airport, the baggage claim clicks and clacks while tour companies try to sell tourists on overpriced day trips and Jeep rentals. I’m awaiting my bags and finally starting to adjust to the humidity in the Caribbean. “Shaun?” someone says behind me. I turn around and see a short-haired, scruffy guy, average build. “That’s me! You must be Clayton.” Sure enough, it is Clayton Pollock, Park Dive Officer in St. Croix. “Mikey Kent [Park Diving Officer at Dry Tortugas National Park] told me not to say hi to you and instead to grab you by the neck and give you a kiss, I think we skip that and just tell him I did,” I say to Clayton. He laughs and says, “ahhh, Mikey, got to love him! Yeah, thanks for not doing that ha ha ha.”

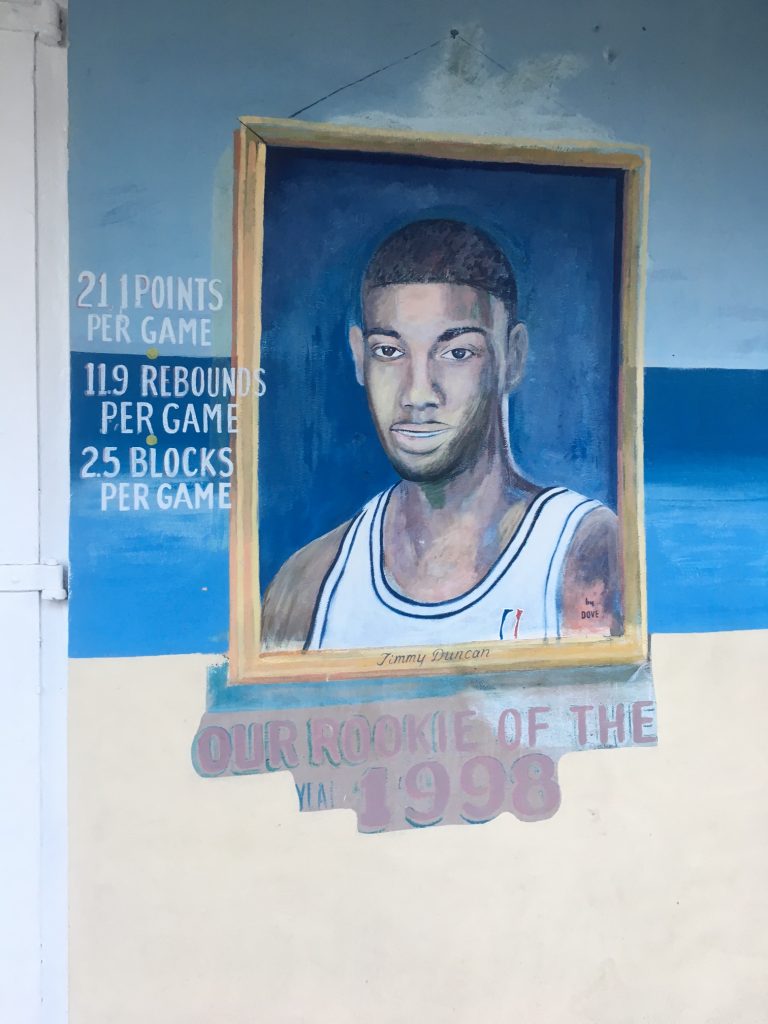

NBA legend Tim Duncan is perhaps the most famous Crucian of all time. Needless to say, Crucians are very proud of him. He’s the first thing you see upon landing in the airport and tributes like this are found throughout the island.

We toss my gear into an old Chevy Blazer. “So where to? Are we going to the Tamarind Reef Hotel?” Clayton asks me. “Actually, I need internet,” I tell him. I knew my connectivity in the Dry Tortugas was going to be limited, but I didn’t realize that meant no connectivity at all. I thought I would be able to work my accommodation out for St. Croix at Dry Tortugas, but that (obviously) did not happen. “Ok, we can do that. Also did you get my email? The lionfish project you were supposed to work on this week cancelled,” Clayton says. This is where Jeff Miller, Virgin Islands resident and National Park Service legend would tell me, “welcome to the Virgin Islands!”

Clayton gives me a tour of St. Croix as we navigate around the island’s abundant pot holes. He points to some housing projects, “So use common sense, but this place is definitely not somewhere you want to be at night.” He also gives me some advice on the local culture, “everyone says good morning/afternoon/evening when they see each other. It’s not uncommon for someone to stop into a store with no plans of purchasing goods just to say hi.”

Denmark owned the US Virgin Islands until 1916 and much of that colonial architecture still exists in varying conditions. Here is a beautiful colonial building in downtown Christiansted.

After a few phone calls and looking on the internet at the park headquarters in downtown Christiansted, we find a hotel since there are no hostels on St. Croix. It’s the cheapest spot in town- $125 per night for a single without a kitchen. Not my definition of pocket change to be sure.

Clayton takes me over to the hotel and hangs out with me in the air conditioned room while I get settled in. “So…tomorrow?” I ask him. Throughout my internship so far, I generally don’t get briefed on what I’m doing until the night before or day of. I like to think of myself as a free spirit, so this works well for me. “I’d like to get you out with some researchers from the University of Florida that are working on a seagrass project. Let’s give them a call.” Clayton dials Alex Gulick, a Ph.D. student at UF. “Good afternoon!” Clayton says. Clayton is very laid back and is one of the funnier people I’ve met this summer, but right now he is in professional mode. Alex seems caught off guard, “ummmm, hi?” she responds. Clayton informs her that I can either be an extra set of hands for the project or be the photographer for the day. Alex waits to make a decision. “No worries, I’ll be ready either way,” I say, “but if you see Alex tonight, just let me know.” Clayton responds, “full disclosure- I’m seeing Alex, so I will be seeing her tonight.”

Hurricane Hugo hit St. Croix in 1986 and devastated the island. Many buildings and places never recovered and can be seedy places to hang around.

Once Clayton leaves, it’s time for me to get my bearings on St. Croix. The cost of the hotel meant I couldn’t rent a car. The nearest grocery store is many miles away and the cost of eating out in St. Croix is really high. My options are limited. In fact, I only have one option for groceries- the local liquor store.

The walk to the store is short, but I am definitely getting the proverbial “mad dog” from some of the locals. The Crucians (local islanders) in front of the store make a concerted effort to stare me down as I walked in. The air in the store is stagnant. I get the feeling that neither the man behind the counter nor the food on the shelves have moved positions in 25 years. “Good evening!” I say. Without moving his head, he gives me the smallest eyebrow nod…so maybe this isn’t exactly the friendly culture that Clayton told me about. Regardless, they have food. The plan was to get bread for sandwiches, but the few loaves they have are really moldy. So I grab 3 cans of beans, hot sauce, all spice, oatmeal, peanut butter, and a few mangos- ingredients to make a surprisingly delicious backpacker feast without a kitchen.

Alex arrives at my hotel with her two interns, Ashley and Laura, to pick me up in a champagne colored pick-up truck. I hop in the front with Ashley and Alex. “Put in me in gear Ash!” Alex exclaims as rain begins to tap dance on the roof. Ash’s responsibility in the truck is to shift the gears for Alex. The truck is a tight squeeze with all of our gear and 4 people, so the gear shifter is right between Ash’s legs.

Later on, the tables turned. Here’s Alex ready to shift gears for Ash.

We get to the boat and begin to load up alongside many iguanas. Alex’s dissertation research is focused on the effects that turtle grazing has on seagrass communities. To study this, she is monitoring both grazed and ungrazed seagrass sites, as well as creating grazed sites by cutting seagrass to mimic turtle grazing. To account for variation between sites, Alex constantly records temperature data and takes sediment cores, both of which may affect seagrass growth. In order to monitor grazing sites, she sets up underwater cameras intermittently. “I was wondering why we weren’t seeing turtles at some of the sites until last week. We saw a big 10-foot tiger shark cruise our camera, that freaked everyone out a bit. Looks like I know what’s happening to the turtles!” Laura lights up, “I’m hoping we see it out there one of these days!” Alex puts things into perspective, “We have a bet going. I owe these guys dinner if we see it, but we won’t. Clayton has logged over a thousand dives in that area and has never seen a tiger there.”

I start up some small talk getting to know everyone. Ash and Laura are both from Florida. “I’m from Oregon,” Alex states. Hearing this, I can think of only one response, “west coast, best coast!” Alex laughs, “Yes! You must be from California.” I chuckle and ask, “is it really that obvious?” Over the course of my time in the Caribbean, I find that it is that obvious from my demeanor, style, and speech. I get called out for using words such as “burly” and “rad” that aren’t used nearly as much elsewhere apparently. The west coast is a small community when it comes to marine science, and it turns out that Alex and I have many mutual friends, including OWUSS’s own Jenna Walker. Alex is really laid back, almost a bit happy-go-lucky, and admits that she’s “the biggest wimp ever” when it comes to cold water after leaving Oregon many years ago.

Excuse me ladies, can you please keep the sand on the seafloor? Sand in the water column was a challenge on this day for me. Meanwhile, Alex (left) and Laura use scissors to artificially recreate turtle grazing on a study plot.

Once we are at the research site, my job is to take photos documenting the process and to sediment cores back to the boat. Photographing work in seagrass beds is difficult. The sediment composition ranges from sand to silt and gets stirred up really easily. With lots of sediment in the water, a good photo can turn into a bad photo within seconds. Between dives, everyone tells me really funny stories about Clayton and Alex recalls the phone conversation she had with him about me yesterday. “He called and said, ‘good afternoon!’ and I was so confused! I was thinking, hi…honey… He gets really awkward sometimes when he puts on his professional face,” she says as we all laugh.

- Alex (left) hammers a PVC cylinder into the sediment to take a core sample while Laura keeps it steady.

- Laura is ready to put a cap on the core cylinder as Alex pulls out a nice sediment core.

After a few sites, Alex and Laura hop in to move some cinder blocks that mark sites. They do this with their fins off and run on the bottom of the ocean with the blocks in hand. It is quite a site and Laura is particularly excited to get some photos of herself running the blocks around. I descend with them. I set up my strobes and turn my camera on. I set my aperture, shutter speed, and ISO, then go to press the trigger. Nothing happens. I check to make sure I have everything set properly and try again. Nothing. I check the battery, which was at ¾ to start the day. It’s dead! I’m shocked, these batteries usually last 3-4 days and this is the second day I’ve used this battery. I’m disappointed that I can’t get any shots of Alex and Laura running with the cinder blocks on the ocean floor and feel like I let them down. I take some GoPro video instead, but it’s certainly not as good.

Back at the dock, a friend of the crew meets us as we pull in. He says hi to everyone as we tie up and asks about our day. Then he looks at me. “You look familiar,” he says. In my head, I’m thinking that he really doesn’t look familiar, but Alex looks at me and says, “well, he is from LA!” After some talking, we realize that we were in the same class at a high school in LA for 2 years before I transferred out. “Jeff Jung! Yeah, of course I remember you! That is wild!” I haven’t seen Jeff in 10 years, we haven’t even keep up on social media. He’s been living out on St. Croix for a few years working for a sailing-based tourism company after feeling burned out on the rat race of the biotech world. “So…Taco Tuesday?!” Jeff asks the group. Everyone is up for it, and we take off for Maria’s, the only taco place on the north side (or perhaps all) of St. Croix.

I ride with Jeff to Maria’s and catch up. Jeff has established quite the life for himself on St. Croix and found a nice community. He’s a really warm person that makes you feel like he’s been your friend forever, which is impossible to not appreciate. He’s an incredibly positive and upbeat person as well, and has an open mind when it comes to trying new things, like fire dancing and couples yoga.

Spoiler alert! Lots more fire dancing photos to come, but here is Jeff and his lovely girlfriend, Kristen, combine two of their favorite activities- yoga and fire dancing.

After a delicious meal at the restaurant, I get a call from Clayton. “Hey buddy, I think we have found a spot for you in park housing, but it’s far from where you’re working and you’ll need a rental car.” This is welcome news. Park housing is about $70 per night cheaper, including my rental car cost. The rest of the night I do the less glamorous responsibilities of this internship- turning in expense reports, blogging, editing photos, prepping camera gear, and working out logistics for the next two parks I’m visiting- while enjoying a surprisingly delicious bowl of all spice-hot sauce-black beans. St. Croix has been pretty slow for me so far. At my first two stops, the stream of work has been constant. The slower pace of St. Croix is strangely uncomfortable. I feel like I’m being irresponsible almost- like I should be doing work in the field, but I’m not. Furthermore, because I’m not working with a team this week in St. Croix, it feels a little bit isolated. I’m not surrounded by people all the time and the park staff is gearing up for turtle season, so they haven’t been able to hang out with me. It’s not a bad thing, but I would like to find a bit of a community on St. Croix.

It’s 7:00 AM and it’s pouring rain. St. Croix is quite a rainy place. It rains about 8 times everyday for about 20 minutes each time. However, today and tomorrow are supposed to be particularly stormy. Today I’m supposed to be diving with a professor from the University of the Virgin Islands (UVI) named Bernard to do some lionfish tagging. Bernard told me that the captain will decide by 8 whether we will be going out and we will leave by 8:30. Timing is everything this morning, because I’m moving into park housing today. Clayton is coming to pick up my gear that I’m not using today and storing it at park housing. I’m checking out of my hotel, taking a taxi to meet Bernard, and then picking up a rental car after the day of diving.

At 8:15 AM, I still haven’t heard anything from Bernard. I check in with him and he says that the captain hasn’t decided, but if we go, we are still leaving at 8:30. I hold off a little longer, and then check out. I begin unloading my camera and dive gear at the dock at 8:40, still unsure of whether we are leaving. Just as I close the trunk of the taxi, my phone whistles at me. “Sorry Shaun, but we are cancelling today. Weather is too rough, don’t want to risk it.”

I get right back in the cab and head to the rental car storefront. “What’s the cheapest car you have?” I ask. After a few touches of the keyboard, the man behind the counter says to me with a thick islander accent, “right now, I can’t get you a car mon.” Luckily, there is another rental car place nearby. I throw all my camera and dive gear over my shoulder and go to the next rental car place where I get a tiny, but ideal Toyota Yaris. My first stop before heading to my new abode is park headquarters to pick up my things. Driving in downtown Christiansted can be challenging. Almost all of the streets are one-way, many intersections have no stoplights or stop signs, and everyone drives on the left-hand side of the road even though the driver’s side of the cars is on the left.

Keep Left! The rental cars come with a surprisingly useful sticker on the window as a reminder.

“What are you up to the rest of the day? Nothing?” Zandy Hillis-Starr asks me at park headquarters. I was going to get some computer work done, but I didn’t have hard and fast plans. “We can’t have you resting on your laurels! Let me make some calls.” The first time I met Zandy, she looks at me and says unexcitedly, “you do the blog thing, don’t you. You better not put me in it!” Zandy, I tried, but you wrote yourself into the blog today. Zandy is well-organized in an old school way as she shows me her rolodex and paper calendar. If anyone has seen it all, it’s her. She grew up on St. Croix and has worked for the park for over 30 years.

One thing that Zandy asked me to do was get a photo of “the bulletin board.” USPS used to be downstairs at park headquarters and had a bulletin board on the wall. When they left, the inside of the wall was exposed. Turns out many colonial buildings in St. Croix are built using coral.

After a few phone calls, Zandy sets up a two-tank recreational dive the next day for me. She’s sending me out to get photos of divers at Salt River, which is an area under park jurisdiction. She also tells me, “You should dive the pier at Frederiksted tonight, you might see frog fish and seahorses, plus the pilings are covered in colorful organisms.” I thank Zandy for her help and advice, and take off for the grocery store.

Park headquarters is situated across the street from Fort Christiansted. The fort was built primarily to smother slave rebellions and secondarily to protect the cash cow (in the form of sugar and rum production) that was St. Croix for the Danish government.

Clayton told me the best grocery store on the island is Plaza Extra. Fortunately, it’s right next to park housing. Entering Plaza Extra is a fairly overwhelming experience. It is a massive store, slightly smaller than Costco, with much less open space and far fewer visual references. There are at least two, often three places in the store for the same item. If you see an item you want, you may want to hold off because there may be a larger selection on several other isles. The store is really a microcosm of life on the island; it’s inconvenient, poorly organized, and fairly hectic, but it doesn’t seem to bother anyone and most everyone is happy to be there.

Once I get to park housing, I look at the paper that has my house assignment on it, “house 2, room 2.” None of the houses are numbered, so I take a guess that the second house in is mine. My key works to unlock the door, and I look for my room. None of the rooms are numbered either. I leave my things in a room that looks mostly unoccupied. Eventually, my housemate Devon comes in.

Devon is a tall, blonde woman who is as quirky as her collection of tattoos. She is an intern for the carpentry team, which is park of the National Park Service’s Historical Preservation team. I’m impressed with Devon’s attitude and mental fortitude. She works 5 AM to 5 PM on top of a scorching hot roof as the only woman on a team of salty carpenters. She enjoys a bag of popcorn and a La Croix everyday after work and loves dogs and goats. We chat for a bit before I have to pack up and head to Frederiksted for my night dive at the pier. Since I do not have phone service (meaning no GPS) on St. Croix, I have leave particularly early in case I get lost.

It’s alive!!! The pilings at the Frederiksted pier are teeming with life and color.

Frederiksted is a curious place. As I walk around, young crucian men blast hip hop and burn out their tires on their lowered Honda Civics. The buildings in Frederiksted are either immaculate or derelict, there are very few that don’t fit into this category. Hurricane Hugo devastated St. Croix in 1986 and much of the island never recovered.

I was shooting this structure near the pier when this spotted moray eel wanted some face time with the camera. Truth be told, I never saw the aspiring model until I uploaded my photos to my computer.

After a lengthy dive brief at the dive shop, we hop off the pier and turn on our lights. The pilings are beautiful. Bright yellows, blues, reds, and oranges. Almost everything we see would require using a macro lens, which I do not have. I’ve learned to just enjoy things underwater even if I can’t get the shot. About halfway through the dive, we see a frogfish. I nearly screamed in my regulator. I’ve always wanted to see a frogfish. Their pectoral fins are reminiscent of a frog’s front arms, equipped with tiny hands and all. They can use these fins to “walk” on the seafloor or down a piling, which is exactly what this fish does while I’m watching it. It is unbelievable and rare to see. It’s like seeing evolution right before your eyes. The fish literally just walks right down a piling in front of me. The rest of the dive is filled with octopus, fish, and more bright colors, but I will always remember the frogfish.

Frogfish! Notice the little hand-like pectoral fins this fish has. Without a macro lens (used for close up shots), getting this photo in-camera is impossible. This is a heavily cropped version of a photo that included nearly the entire piling. Even though I was about 8 inches from the fish, a wide angle lens has a giant field of view.

“We’re going to try to get to Salt River! Weather is a bit rough out there.” The scuba shop manager says to me. I’ve heard this story on St. Croix before. Another day of rough weather means there is no guarantee I’ll go to the wall at Salt River, which is what Zandy sent me out to do.

Less than ideal conditions at Salt River translated to mostly black and white photos to help cover up turbidity in the water.

There are only two other divers going out today, so I don’t have a lot of divers to shoot. We decide to give Salt River a shot. We keel pretty hard on the water, taking the 7-foot swells directly off of our starboard side. Once we are at Salt River, the visibility isn’t ideal, as the big swell stirs up sand and the rain pushes sediment from the land into the ocean.

Capturing the grandiosity of the wall was an impossible and frustrating aspiration for me. This is as close as I came.

Reduced visibility makes photographing the wall that we are diving particularly challenging. It’s impossible to show the wall’s grandiosity since I can’t see it, with or without my camera. Furthermore, since this is a guided dive and we are not going to come close to our no-decompression limit, we are constantly on the move. It was difficult to get in front of the group. To get a good photograph of divers, you generally want to be in front of them; shooting them head on and from slightly below. I can’t swim fast enough with the camera to get in front of the divers and set my shot up. This dive was a frustrating photographic experience for me. I’m still coming off the high of Dry Tortugas National Park, where I was really happy with some of the photos I got. I feel like I let Zandy and the dive shop down by not getting any shots I was particularly proud of.

The barge is home to many vertebrates as well as colorful invertebrates, seen here.

Our next dive is at a wrecked barge close to Christiansted. The owners of the barge asked the government of the Virgin Islands if they could sink the barge and turn it into an artificial reef. The government was going to charge them a lot of money to do so and told them to leave St. Croix if they weren’t going to pay the fine. Coincidentally, on their way out of St. Croix the barge “accidentally” sunk.

This turtle flew by us so fast as we descended. Swimming towards it was ambitious at best. I was lucky to get any shots off.

We descend onto the barge and I immediately see stingray, a green turtle, two reef sharks, and a school of fish. What do I shoot first?! I whip the strobes into position and do my best to set my exposure while swimming as fast as possible towards the speedy turtle. After shooting the stingray, we swim down to the barge, which is covered in reef sharks that aren’t too nervous about crusing divers.

- When I showed Mike Feeley (South Florida Caribbean Network) my photos of the sharks from the barge, he reminded me that I was lucky to come away unharmed in this instance.

- Our dive leader warned that the barge wasn’t a very interesting structure, but I thought it was pretty cool.

Because many dive shops cull lionfish in the area and leave them for the reef sharks, the sharks started to display semi-aggressive behavior when I sat around them for the while, expecting food from me. They were flexing the pectoral fins downward as I was trying to get as many pictures as possible. Because they were swimmingly quickly so close to the bottom and I was slightly nervous (for the first time after diving with many, many sharks), it was difficult to shoot them.

- WANTED: Nassau groupers. These fish have been protected for decades but have yet to make a comeback. I’ve been lucky to see a few this summer, but do to their skiddish nature, I hadn’t been able to take a photo of one.

- Coming onto a bright patch like this makes my job pretty easy as a photographer.

Night falls. The air is heavy with humidity and drink glasses are clinking as tiny ripples lap against the boardwalk of Christiansted. I’m out with Devon and the construction crew when I see Jeff and his girlfriend, “Shaun!! Get over here!” he calls out to me. We catch up and I meet his crew of St. Croix friends. It’s the first time on the island I’ve seen and felt a sense of community. A small group of friends from all over the US that seemingly all work in tourism or yoga. They are genuinely happy to have me around as much as I’m genuinely happy to be there, and waste no time integrating me right into the group.

“So if we see a turtle, we make the decision whether to relocate the nest or not. I generally error on the side of not relocating them. Turtles have been turtles for thousands of years and know way more about nesting than I do” Clayton tells the group. If turtle nests (which contain turtle eggs) are in a spot prone to erosion and can be swept out to sea, the turtle team will encourage the turtle to move spots or carefully relocate the eggs. It’s not an easy decision, because relocating a nest lowers the hatch success rate considerably. “It’s the first night of turtle season, we aren’t going see a turtle, no way! I will buy you all ice cream if we do,” Tessa Code chimes in (more on her next blog). I jokingly fire back, “not with that attitude!” Nathaniel Holloway then speaks up, “do we have all of our packs? Everyone has a red light? We have all the radios?” The turtle interns all assure him we have the gear we need as the sun goes down and our vessel casts off for Buck Island.

The NPS team gets ready for a opening night of the turtle season on Buck Island. From left to right: Clayton Pollock, Alex Gulick, Nate Holloway, Tessa Code.

On the island, I notice Clayton is wearing a different pair of Crocs than he normally wears. They are dark and lined with some suede-like material on the outside. “These are my suit and tie crocs, I keep it classy on Buck Island!” The NPS team then splits into teams and begins walking the beach. We drag our feet into the sand to create a visual reference line. If a turtle comes onto the beach, there will be a break in the line. Places in which we cannot put a line, we put up “knock downs,” or sticks that a turtle would have to knock down to nest in that location. I’m walking around with Clayton and Nathaniel’s team.

The team draws out a line in the sand to help create a visual reference for a potential turtle nest.

Nathaniel is a big, tanned man who sports a man bun. I get the feeling it would take quite a bit to irk him. He speaks with a low, calm voice and never hesitates to interject his quick-witted sense of humor into conversation. Nathaniel and Clayton have a hilarious relationship. It’s a “bromance,” in the most classical sense. They constantly compliment each other on their clothing, jokingly wink or blow kisses at each other when they pass by in hallways, and finish each other’s sentences. On the beach, they stop the interns and me periodically to offer some turtle wisdom. “Sometimes they get way back into this vegetation and are almost impossible to see,” Nathaniel starts. “Stop and smell around, turtles stink,” Clayton says. “Exactly! Great point Clay!” Nathaniel responds as they both chuckle.

Once the lines are drawn and knock downs are put up, it’s time to monitor the beach for turtles. Teams monitor the beach so that every stretch of the beach is covered every 45 minutes (if not a shorter period). We walk the beach under millions of stars and the milky way band just starting to show. All the while, I’m nearly falling asleep. The turtle team is on a 6PM to 6AM work schedule. I have been on the exact opposite schedule the entire summer. Luckily, this is only a half night of turtling for me. When we are not walking the beach, we are waiting on the dock for a radio call about a turtle sighting. Since it’s the first night of turtle season, we all get to go to a turtle if we see one.

Being on Buck Island at night was a special experience, but I got my tail handed to me on the late night shift. Transitioning from a day-time work schedule to a night-time work schedule in one day was tough.

The night ends with Tessa not owning us ice cream. We didn’t see a turtle, but it was a great experience to see how turtling is done. I came away from the experience with a much higher respect for “turtlers.” The job is as mentally demanding as it is physically with a brutal work schedule. My work schedule doesn’t get any easier tomorrow.

“Are those tanks full? The caps are off and the feel a little light to me,” I ask Sarah Heidmann as I analyze nitrox cylinders for our day of diving. “I hope so, I dropped them off early yesterday and they knew we needed fills,” she states nervously. I connect a pressure gauge to the cylinders. Sure enough, they are empty.

“Hi Nicky, we are going to be running late. Sorry for that, we are just getting the cylinders filled right now,” Sarah is on the phone with our boat captain for the day- a local fisherman named Nicky. As we are waiting for the cylinders to fill, Sarah and I get talking. She is finishing up her master’s degree at UVI and has been put in charge of the project we are working on. We are picking up acoustic receivers that track mutton snapper. The university catches mutton snapper, inserts an acoustic tag into their stomach, and that tag then sends a signal to these receivers every time a tagged fish is near. This data will inform the research team about where the fish spawn and aggregate, highlighting important geographic regions to protect.

Sarah is from the San Francisco Bay area, so of course we know some of the same people, being that the west coast marine science community is apparently bite-sized. “Brynn Fredrickson?! Yes! We were dive buddies under Jenna Walker at the Oregon Coast Aquarium!” Turns out Sarah knows Our World-Underwater Scholarship Society’s own Jenna Walker and Brynn, my friend and colleague at my Catalina Island home.

This is certainly a nervous smile from me around Molasses Pier. Also pictured (L-R): Nicky, Sarah Heidmann, Kristen Ewen, Elizabeth Smith.

We pull into an open-air market that smells strongly of both fish and mango, where we meet two other UVI students helping out for the day. Their names are Liz and Kristen. Both are originally from the states but seem very at home on the islands. Between the three UVI ladies, there is a strong synergy, a wealth of dive knowledge, and a lot of blonde hair.

“Where is our fisherman…” Sarah ponders for a minute as we pass by a pile of dead fish on ice staring us down. We see a truck with a trailered boat behind it. There’s Nicky. He is a Puerto Rican by birth but has been living on St. Croix for many decades. “Just go straight up this hill,” as he points in many vague directions, “I’ll meet you at Molasses Pier!” Needless to say, those directions weren’t the best. Fortunately, Sarah has data service on her phone and brings up Google Maps. “Well, Molasses Pier doesn’t exist on here,” she tells me as I’m driving up one of several straight hills in the area.

We end up taking the “scenic route” and arrive at Molasses Pier. It’s in a highly industrial area on the south side of the island. There is no actual pier. It looks more like some cinder blocks fell into the bay and the local fishermen said, “great! We’ve always needed a boat ramp here!” Molasses Pier is the sketchiest place I’ve been all summer. It’s desolate and industrial. I equate it to Tattoine in Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope. You can’t see them, but you know the Tuscan Raiders are in caves watching you, ready to rob you. All the while, you are hoping a big local fisherman chases them off for you, Obi-Wan Kenobi style.

We could use the protection of Fort Christiansted (pictured) at the pier.

“You launch from here often?” I ask Nicky. “No, never, I hate launching from here. They like to vandalize your things here. Leave your car doors unlocked and take everything out. They are going to break into your car and you don’t want a broken window.” Comforting, especially since I have a rental car with a stereo in it.

On the water, the diving is unlike any I’ve ever done. We are doing deep “bounce dives,” where we will descend to 80-120 feet to retrieve an acoustic receiver. The dives are no longer than about 7 minutes. Conditions vary constantly throughout the day. One minute it’s calm and sunny and the next we are taking on 6 foot swells and the rain is pouring down.

The real highlight though is Nicky. He is quite the character and I’m never really sure if he knows what he’s doing or not. His behavior indicates that he has things really under control and knows his boat well. His stories, and there are an infinite number of them, tell a different tale. “Last time I saw the [the local hyperbaric chamber operator], they said, ‘you?! Again?!’” Not exactly what you want to hear as a diver. However, his stories definitely made the day fly by during my surface intervals. From getting cruised by a cargo ship while he was underwater on a dive, to being left behind by a dive boat and swimming 5 miles back to shore, to taking his 25-foot 180-horsepower boat to Puerto Rico to handline for wahoo and tuna, there is never a dull moment with Nicky. “My sons and I wear this bike tube on our fingers, otherwise the fishing line can take off a finger!” he says as he shows me how he brings in 150-pound fish by handlining. Most of his stories involved his family members, and he took us on as if we were one of them.

Since I couldn’t take my camera on Nicky’s boat, here’s another shot of the Fort. The Fort isn’t mentioned much in my blog, but it is quite the site. I didn’t know about the Danish rule over the islands until I got there, and the fort was a huge part of that learning experience.

After we pick up 16 receivers, we are done for the day and head back to Molasses Pier. “Woah! Speed bump!” Nicky brings the boat to a quick stop. “The fishermen call turtles speed bumps because you have to slow down when you see one!” We see a few more “speed bumps” and arrive back at the Molasses Pier to be greeted by Nicky’s family. To no one’s surprise, they have all come down to help trailer the boat and offer a little bit more protection from potential criminals in the area. They are as warm as Nicky and help us load our cars as well (luckily, mine still had the stereo in it).

That evening, I decide to meet up with Sarah, Liz, and Kristen. They are with Madeline Roycroft, a Ph.D. student at California Polytechnic San Luis Obispo (SLO), and her undergraduate assistants Ali and Maurice. Madeline is a southerner at heart but looks like she has integrated into the California lifestyle well, sporting Chaco sandals and Patagonia clothing. Her outspoken and extroverted undergraduates provide a ying to her more reserved yang. The UVI ladies and Madeline’s group have found a community on the island amongst themselves and get along fabulously.

Between my old friend Jeff, Clayton and NPS, the UVI ladies, and the SLO team, I am beginning to start to feel at home at St. Croix. It feels much less isolated than it did earlier in the week. The more people I meet around the island, the smaller it begins to feel, and I enjoy that. I’m also learning to enjoy my off time. I get so eager to cram in as much NPS work as possible during my short summer that I can forget to enjoy the wild places I get to travel to. St. Croix has taught me how to slow down and given me the most independence of any stop this summer. Week one could best be summed up as “unexpected,” but as I continue to settle into life in the Virgin Islands, I’m looking forward to working with the NOAA conch tagging team next week and continuing to lay down roots here.

Dive Briefing by Rich Walsh

Dive Briefing by Rich Walsh