My second week in Kalaupapa has been packed with diverse and unique experiences. We started the weekend with a trip to topside Molokai to get groceries. Sly, Rafael Torres, and I donned our packs and started up the three-mile Pali (cliff) trail, which includes 26 switchbacks and over 1600ft of vertical cliff. The only means of land access to Kalaupapa, this is the same trail that brought mail, supplies, and visitors to the colony in its heyday. Today, the main users of the trail are guided mule trips that bring visitors to spend three or four hours at the settlement. Near the top, we did our part to curb invasive species by snacking on strawberry guavas, and were rewarded by the incredible view of the entire peninsula at the final overlook. In town, we perused the farmers’ market and got our essentials at the various grocery stores, stopped for local flavors of ice cream, and headed back down. We had just enough time to catch our breath and unload groceries before gathering for community volleyball, a twice-weekly event. Eighty-three-year-old patient Uncle Lelepali organizes and referees each game, and his calls are law. Players of all ages and agencies, permanent residents and visitors like myself, assemble each Saturday and Wednesday evening to rotate around the pitted grass court, while spectators chat and pass around six-packs from the settlement bar across the street. Laughter, cheers, and good-natured heckling fill the air until it’s too dark to play and Uncle Pali cries out a final, “Shake hands!”

The view of the settlement from the top of the Pali trail.

Community events don’t stop at volleyball. The (admittedly limited) younger crowd often meets for ultimate frisbee or a game of pool, and everyone invites each other over to watch the University of Hawaii women’s volleyball games or, in the case of law enforcement officer and die-hard Auburn fan David Ellis, the kickoff of the college football season. I was also encouraged to attend a mass in the historic St. Philomena church in Kalawao. Religion is a central part of life for many in the settlement, and the Catholic Church in particular is a big presence here, especially since Father Damien was canonized as a saint in 2009. Saint Damien worked in the settlement in the late 19th century, built St. Philomena, and was loved for his compassionate treatment of the patients at a time when they were misunderstood and mistreated. St. Philomena has been restored to its original appearance, and the community holds a mass there once a month (there are places of worship for several denominations in the Kalaupapa settlement, but these monthly services in historic structures are particularly special cultural events). Kalaupapa’s Father Patrick delivered a beautiful and lighthearted homily, and a visiting church group provided rousing music. After the mass, patients congregated on the church grounds, and I met and chatted with the aunties and uncles, several of whom shared snippets of their stories.

Over the holiday weekend I learned more about the history of the settlement, reading several patient memoirs and Kalaupapa-related literature. Although today the patients are considered the community elders and command the utmost respect, historically Kalaupapa has been a place of great suffering. Hansen’s disease was poorly understood and highly stigmatized, and mandated quarantine meant families torn apart and victims sent to a life of exile. Most histories also gloss over the native Hawaiian communities that were forcibly removed from their land when the settlement was created. The patients that live here are true survivors, and I’m amazed by the incredible joy, humor, and goodwill they maintain. It is truly an honor to come here and be a part of this community, however temporarily.

The weekend over, I reported to the NPS office at 7am. The first task of the week was tagging a monk seal pup that had recently been weaned. Ten pups were born in the park this summer, a new record. This particular pup was a female, crucial to sustaining the population, and Eric and Randall had been waiting for her to get in a good tagging position for weeks. They want to tag the seals right after they’ve been weaned, while they’re small enough to be restrained, but they must wait until the seal is out of the water and away from lava rocks that could injure the seal or the taggers. Eric and I drove to the beach where the seals usually haul out, and luckily enough our pup was sleeping in the sand, in a perfect tagging position. I kept watch from behind the low-hanging pines while Eric radioed Sly and Randall and they prepared their tagging material. The seal was still rotund with baby blubber, occasionally trying to brush flies from her face with flippers that could barely reach over her chubby shoulders. The tagging team emerged, decked out in blue coveralls, and got to work quickly and efficiently to minimize time spent handling the seal. Randall restrained her while Eric and Sly attached red plastic tags to her tail and took tissue samples for genetic data. Less than five minutes later they released her and she blobbed back into the ocean. “She’s a strong one!” Randall declared. “She’s going to be a good mom.”

The pup shoots us a reproachful glance as she makes her way to the water. The red tags in her tail will identify her and allow scientists to track her movements and behavior over her lifetime.

Afterward, we packed up the water quality sampling gear and headed to Kauhako crater, site of the previously mentioned deepest pond in the world. The pond is only slightly bigger than a backyard swimming pool, but is over 800 ft deep. To hike down to the crater we had to fight through the heavily overgrown Christmas berry and use ropes to navigate loose rocks and soil on the steep trail. At the pond, which was a curious greenish-brown color, we ran the Sonde device and took water quality samples. The water was so full of algae and particulates that our filters clogged immediately. Eric also retrieved and redeployed temperature and water level loggers they’re using to track long-term weather and climate data.

This waterfall cove is one of our favorite lunch spots.

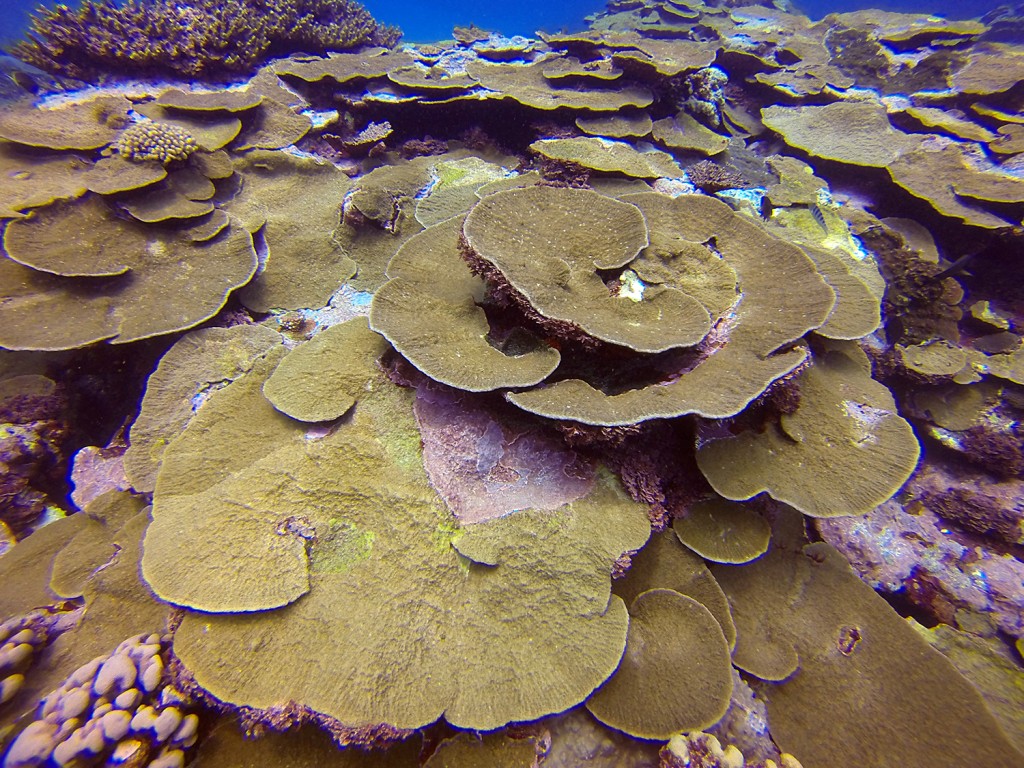

This was all the first day of work, and we still had a dive planned. Eric first briefed me on their fish and benthic survey protocols. They perform the surveys along a 25m transect, at several fixed sites as well as random temporary sites that vary year to year. The fish diver goes first, identifying, counting, and sizing the fish he sees, similar to the fish counts we did in St. John. The benthic diver, rather than recording data during the dive, takes a picture of the benthic substrate at each meter of the transect, using a monopod and fixed focal length for standardization. The photos are processed on land with a computer program that puts random dots on each image, and the analyzer records the benthic species or type of substrate intersecting each dot. They also measure rugosity, the complexity of the habitat, which tends to correlate with fish size and abundance. For this survey, one diver follows the topography of the habitat underneath the transect line with a 10m brass chain while another diver helps spool out and reel in the chain above him. A greater total length of chain used indicates greater rugosity. Water quality samples and Sonde measurements are also taken at certain sites. To spare me the task of learning all of Hawaii’s incredibly diverse fishes in a few days, I was assigned benthic photography and rugosity assistance duties. We did a practice run on land so I could get used to setting the white balance on the camera and using the monopod, and then headed to the pier for a check out dive and another practice run. It felt a little silly to bring so much gear down and not leave the harbor, but the trial was definitely worthwhile. It took me a few tries to find a strategy for balancing the camera in the slight swell, and after snarling the chain the first time I reeled it in, I learned to coil it carefully to prevent future tangles.

Unspooling the chain for Randall during a rugosity survey.

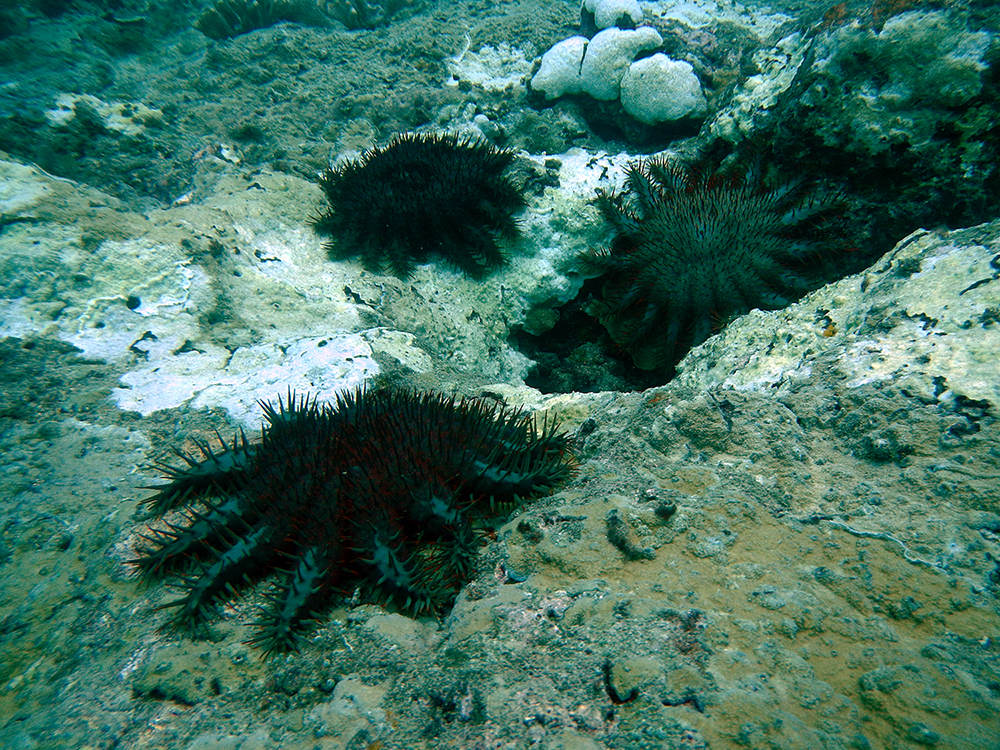

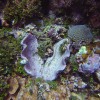

The next day, all the kinks (brass and figurative) worked out, we jumped into our actual surveys. They were on the eastern side of the peninsula, and we passed by Kalawao and Waikolu. The underwater habitat generally consists of big boulders with scattered coral and sweeping schools of fish. Lagging behind the fish divers and focused on the benthic substrate I was often oblivious to the more rare and exciting sightings Eric and Sly would exclaim about on the surface, but I was still blown away each time I looked up, and loved searching for colorful crabs and eels hiding in the coral. On the boat we collected water quality samples with Niskin bottles, which we lower to our decided depth on a line, and then send down a weight to trigger and close the spring-loaded lids. We would stop for lunch by the tiny rock islands scattered along the coast, or tuck into protected coves with striking lava formations and waterfalls.

Okala, the triangular island, contains an underwater cavern.

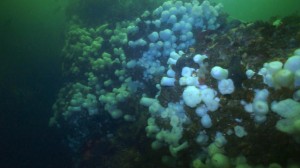

As we approached our last site on Thursday afternoon, we were surprised to find a boat anchored almost exactly where we were headed, with snorklers and divers in the water. We waited a bit, and as one snorkler surfaced we realized they were spearfishing. While fishing is technically legal in these waters, there is a long history of respecting Kalaupapa’s resources both as protected by the National Park and rightfully belonging to the patients. We radioed in to the rangers and they came to make a “courtesy call” to the fishermen. They were from Oahu and unaware of the customs here, but were cooperative and departed to fish further from the Kalaupapa coast. Our fish count arguably somewhat lessened, we completed the site. As a special treat, Eric then brought us to an incredible site to check out the spread of a non-native snowflake coral, Carijoa riisei. Okala, the triangular rock we had been boating around for the past few days, is actually an archway that creates an underwater cavern. Its walls are covered in amazing sponges and invertebrates, as well as the lacy snowflake coral. After inspecting the snowflake coral and taking in the general grandeur, I followed a Spanish dancer nudibranch as it fell from the wall and unfurled in the sand. It was about eight inches long, by far the biggest nudibranch I’ve ever seen (although apparently they can reach 15 inches!). Sly and I then surfaced in the small air pocket at the top of the cavern, and had a brief conversation, which mostly consisted of reminding one another of how awesome it was to be having a conversation inside Okala. On the way out we circled around the island, a sheer wall crammed with brightly colored sponges and zooanthids, a huge contrast to the bare boulders flecked with pale yellow and white corals of our study sites. I was enthralled by brightly colored fish, tiny neon green gobies scooting along identically colored sea whips, and an enormous octopus that coolly regarded me from within a crevice. It was without a doubt one of the coolest dives I’ve ever done.

Randall swims near the cavern exit.

The Molokai lighthouse, stunning against the cliffs as we pass the point of the peninsula.

At the end of the week, Eric took me on his weekly monk seal survey. We started at the airport and traversed the rocky and sandy coast down to the settlement, identifying any monk seals sleeping on the rocks or sand or playing in the water. By conducting these surveys each week for many years, they can learn more about seal behavior, most importantly how the seals utilize different types of habitat. This will help park scientists determine why the seals are increasingly coming to Kalaupapa to pup, and inform decisions for habitat protection. For example, Eric has found that as pups the seals tend to favor the sandy beaches, but as they mature they’ll branch out to different types of habitat, and are more likely to haul out on rocks. This suggests that if the state or a federal agency were to set aside protected areas for Hawaiian monk seals, they would need to preserve multiple types of habitat. Over the two-hour survey, we saw about a dozen seals on the beaches or in protected pools. If we couldn’t see their tags, we took photographs of identifying features that seal experts topside will compare to existing images. The pup we had tagged earlier in the week was still hanging around the beach, holding her own in a playful and perhaps aggressive encounter with a much larger male. We also did a quick black-tip reef shark count. A large number of these sharks patrol a protected lagoon here, and the park is currently working on studies to figure out why. The sharks are more numerous in the winter months, but we saw three sets of dark fins slice the surface in our five-minute scan.

A remaining untagged pup. We’ll try to come back and get her another day when she’s not so close to the rocks.

The days certainly have been eventful! We have the weekend to unwind, and I’m looking forward to another week of diving and spending time with the Kalaupapa community.

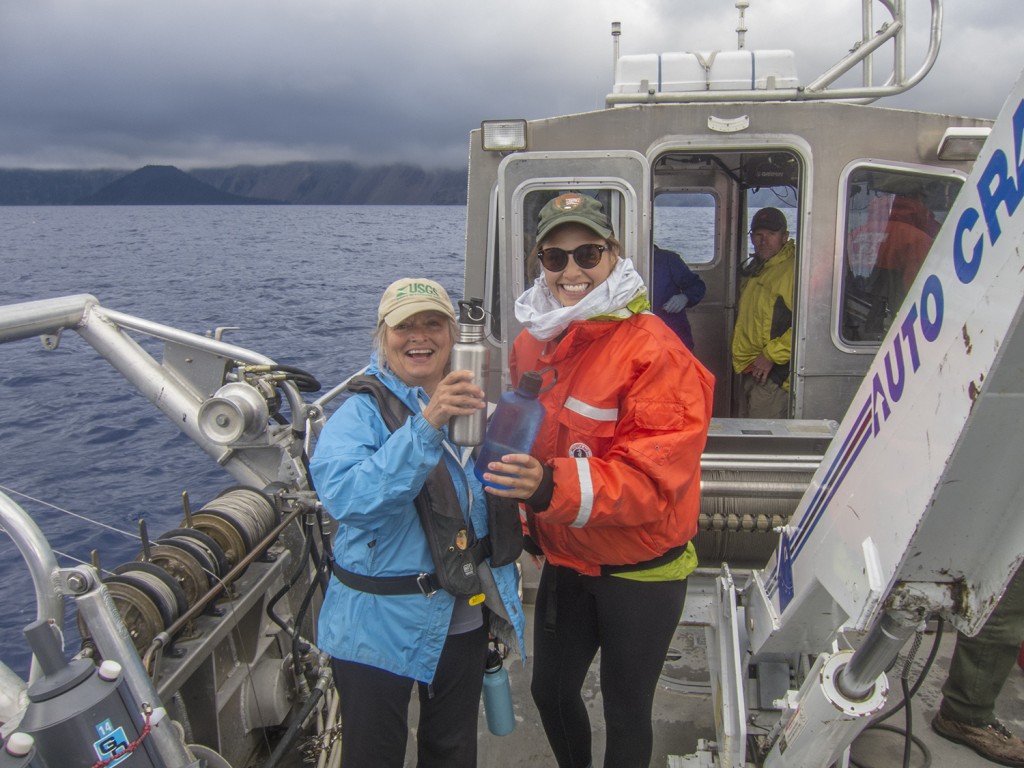

I have used underwater video equipment in the past for benthic monitoring surveys, but I had no previous experience taking still shots, which I found to be much more difficult. My first few pictures came out extremely blurry, but after playing around with the lights and concentrating on steadying my hands shots began to come out clearer and crisper. After the dive, Vallorie showed me how to properly clean and take apart the housing. We took the memory card out and put it into the computer to check out my photos. As we looked over them, Vallorie asked me questions about the photos- How could this shot have been better? What would you do differently about the lighting? How could you have changed the point of view to make a more interesting background? She often teaches me by giving me minimal instruction prior to a task, allowing me to figure out how to do something, and more often how not to do something. Inevitably I make mistakes, but end up learning a lot from the errors.

I have used underwater video equipment in the past for benthic monitoring surveys, but I had no previous experience taking still shots, which I found to be much more difficult. My first few pictures came out extremely blurry, but after playing around with the lights and concentrating on steadying my hands shots began to come out clearer and crisper. After the dive, Vallorie showed me how to properly clean and take apart the housing. We took the memory card out and put it into the computer to check out my photos. As we looked over them, Vallorie asked me questions about the photos- How could this shot have been better? What would you do differently about the lighting? How could you have changed the point of view to make a more interesting background? She often teaches me by giving me minimal instruction prior to a task, allowing me to figure out how to do something, and more often how not to do something. Inevitably I make mistakes, but end up learning a lot from the errors. When we arrived at the top of the pinnacle Jim briefed us on how to best catch an octopus. The easiest method is to lay the bag behind the octopus mantle and then place your hand in front of the octopus. Using this method the octopus will back up on its own into the collection bag. I would be diving with Vallorie and my primary focus was to take photos, although if we saw an octopus we would by all means attempt to bring it up. The ocean was much calmer than last week, and the visibility, at about 7 ft., was not bad either. Due to the relatively mild conditions, Vallorie felt it was a great opportunity to load me with a few more tasks than I would normally take on. I would handle the reel, camera, and navigation. Since we would be using a safety reel tied off to the anchor line the navigation part would not be too difficult, but I still needed to get us oriented in the correct direction so we could find deeper water; I needed to reach at least 60 ft. in order for the dive to count towards my 60ft depth certification. I took a giant stride off the stern, tapped my head to signal I was ok, and reached up to grab the camera. I attached it to the D ring on my right, as I already had my octo, computer, and a reel attached to my left D ring.

When we arrived at the top of the pinnacle Jim briefed us on how to best catch an octopus. The easiest method is to lay the bag behind the octopus mantle and then place your hand in front of the octopus. Using this method the octopus will back up on its own into the collection bag. I would be diving with Vallorie and my primary focus was to take photos, although if we saw an octopus we would by all means attempt to bring it up. The ocean was much calmer than last week, and the visibility, at about 7 ft., was not bad either. Due to the relatively mild conditions, Vallorie felt it was a great opportunity to load me with a few more tasks than I would normally take on. I would handle the reel, camera, and navigation. Since we would be using a safety reel tied off to the anchor line the navigation part would not be too difficult, but I still needed to get us oriented in the correct direction so we could find deeper water; I needed to reach at least 60 ft. in order for the dive to count towards my 60ft depth certification. I took a giant stride off the stern, tapped my head to signal I was ok, and reached up to grab the camera. I attached it to the D ring on my right, as I already had my octo, computer, and a reel attached to my left D ring. Back aboard Gracie Lynn, we were excited to find that Jenna and Brittany had already brought up one octopus- a cute little fellow, about 20 lbs. Jim and Peter geared up and got in the water to try their hand in octopus catching. They resurfaced about half an hour later with a great catch. They managed to get a fairly large 45 lb octopus! We put it in one of the totes and covered the lid so that it wouldn’t feel too uncomfortable. It was a very successful day; we came back with not one, but two octopus, 10 jellies, and I managed to get some great photos. I am very excited to continue working on my underwater photography skills and it is wonderful to have such a great teacher! Thanks Vallorie 🙂

Back aboard Gracie Lynn, we were excited to find that Jenna and Brittany had already brought up one octopus- a cute little fellow, about 20 lbs. Jim and Peter geared up and got in the water to try their hand in octopus catching. They resurfaced about half an hour later with a great catch. They managed to get a fairly large 45 lb octopus! We put it in one of the totes and covered the lid so that it wouldn’t feel too uncomfortable. It was a very successful day; we came back with not one, but two octopus, 10 jellies, and I managed to get some great photos. I am very excited to continue working on my underwater photography skills and it is wonderful to have such a great teacher! Thanks Vallorie 🙂

We entered the water on the western bank, and made our way towards the center of the lake where the depth increases to about 45ft. As soon as we hit deeper waters I immediately wished I had an underwater camera; the crystal clear water reminded me of the tropics, minus the warm water and bustling coral reefs.

We entered the water on the western bank, and made our way towards the center of the lake where the depth increases to about 45ft. As soon as we hit deeper waters I immediately wished I had an underwater camera; the crystal clear water reminded me of the tropics, minus the warm water and bustling coral reefs.

A few days later it was time to try out our new skills in open water. Jim, Vallorie, myself and four other AAUS Scientific Divers set out on Gracie Lynn for North Reef, which was selected as one of the survey sites for the rockfish project. The first buddy team went down to place the block that we would start the survey from. Once they had it in place, they signaled their location by deploying a surface marker buoy, which cued Vallorie and I to get inthe water. We descended along the anchor line and pointed our compasses towards the heading we had taken on the surface. The visibility was only about 5 ft. but within a few minutes we were able to locate the other buddy pair waiting by the block. I clipped the transect tape to the block and we swam south along the wall to conduct the survey. Visibility was poor and the current made it a challenge to remain in proper positioning with Vallorie, but we made it to 50 meters, at which point I signaled to Vallorie that it was time to turn around. On the way back towards the block, the camera housing started beeping, signaling that a leak was detected. We quickly got back to the marker buoy and ascended to care for the camera. Once on board we washed the housing with fresh water and carefully took it apart. This should be the first step any time you suspect a leak in your underwater camera housing. We then placed the camera in a zip lock bag with desiccant pellets in hopes that it would dry out before any damage was done. We were unable to use the camera the rest of the day, but luckily this was just a training day and it was not critical that we collect data. We spent the rest of the dives working on skills such as navigation, setting up transects, and deploying surface marker buoys, and also had the chance to collect invertebrates for the aquarium. Although some may consider the low visibility, high surge water to be less than ideal diving conditions, I feel that the difficult working conditions enhance training dives. If you can successfully handle equipment and manage task loading in these conditions, you will be much better prepared for future dives no matter where they are!

A few days later it was time to try out our new skills in open water. Jim, Vallorie, myself and four other AAUS Scientific Divers set out on Gracie Lynn for North Reef, which was selected as one of the survey sites for the rockfish project. The first buddy team went down to place the block that we would start the survey from. Once they had it in place, they signaled their location by deploying a surface marker buoy, which cued Vallorie and I to get inthe water. We descended along the anchor line and pointed our compasses towards the heading we had taken on the surface. The visibility was only about 5 ft. but within a few minutes we were able to locate the other buddy pair waiting by the block. I clipped the transect tape to the block and we swam south along the wall to conduct the survey. Visibility was poor and the current made it a challenge to remain in proper positioning with Vallorie, but we made it to 50 meters, at which point I signaled to Vallorie that it was time to turn around. On the way back towards the block, the camera housing started beeping, signaling that a leak was detected. We quickly got back to the marker buoy and ascended to care for the camera. Once on board we washed the housing with fresh water and carefully took it apart. This should be the first step any time you suspect a leak in your underwater camera housing. We then placed the camera in a zip lock bag with desiccant pellets in hopes that it would dry out before any damage was done. We were unable to use the camera the rest of the day, but luckily this was just a training day and it was not critical that we collect data. We spent the rest of the dives working on skills such as navigation, setting up transects, and deploying surface marker buoys, and also had the chance to collect invertebrates for the aquarium. Although some may consider the low visibility, high surge water to be less than ideal diving conditions, I feel that the difficult working conditions enhance training dives. If you can successfully handle equipment and manage task loading in these conditions, you will be much better prepared for future dives no matter where they are!

Once we got back to the boat, I climbed aboard and helped to pull up Jim and Roy’s goodie bagswhich held an array of organisms including moonglow and Christmas tree anemones, burrowing sea cucumbers, sea lemon nudibranchs, and a chalk lined dirona, as well as hairy tritons, granular claw crabs and a sharpnose crab. We emptied everything into a barrel filled with seawater for the journey back and pulled up anchor to head back towards the bay. Back at the aquarium, some of the new organisms went to exhibits to be put on display, while others went to the education department. Many of the exhibits in the aquarium reflect Oregon coastal habitats, making local collections a key method for stocking exhibits.

Once we got back to the boat, I climbed aboard and helped to pull up Jim and Roy’s goodie bagswhich held an array of organisms including moonglow and Christmas tree anemones, burrowing sea cucumbers, sea lemon nudibranchs, and a chalk lined dirona, as well as hairy tritons, granular claw crabs and a sharpnose crab. We emptied everything into a barrel filled with seawater for the journey back and pulled up anchor to head back towards the bay. Back at the aquarium, some of the new organisms went to exhibits to be put on display, while others went to the education department. Many of the exhibits in the aquarium reflect Oregon coastal habitats, making local collections a key method for stocking exhibits.