I spent the last week in Pearl Harbor at Valor in the Pacific National Park. Chief of Cultural and Natural Resources Scott Pawlowski was my host for the week and guide to the island of Oahu. He first took me to my housing on the Pearl Harbor naval base: Bachelor Officers’ Quarters (BOQ), housing for transient or visiting officers, which also serves as a quasi hotel for government or military affiliated visitors. I rented a car for the week, a tiny light green Toyota Yaris, and felt very safe each night as I presented my special visitor pass to armed guards each time I drove into the base. On my first day of work, Scott drove me around the base, pointing out historic buildings. Women and men of the Navy were everywhere, some in full uniform, others jogging in characteristic yellow shirts and blue shorts. I was taken aback by how young so many of them were: one gangly member of a trio of joggers still had braces.

When I first arrived, the park was still in the process of stand-up, but there was plenty of work to be done topside. I spent my first few days assisting Retired Chief Petty Officer and current archivist/curator extraordinaire Stan Melman with inventorying the park’s museum collection. They have an extensive collection of artifacts, letters, newspaper clippings, photographs, art, and the like relating to Pearl Harbor and its role in WWII, and not all of them can be displayed at the visitors center. They’ve transferred their records to a computer program, and we were retrieving and checking a randomized list of artifacts to make sure they were in their recorded location and free of damage. It was fascinating—each new drawer and box was full of glimpses into the past, many of them reflecting the gaiety and glamour of life on the base prior to the December 7 attack. We checked off letters to families, a ship’s bell, a program from a boxing match between members of the USS Oklahoma and USS Arizona, and dozens of other treasures.

Pages from a sailor’s album of life on the naval base. This photograph depicts organized calisthenics on one of the ships.

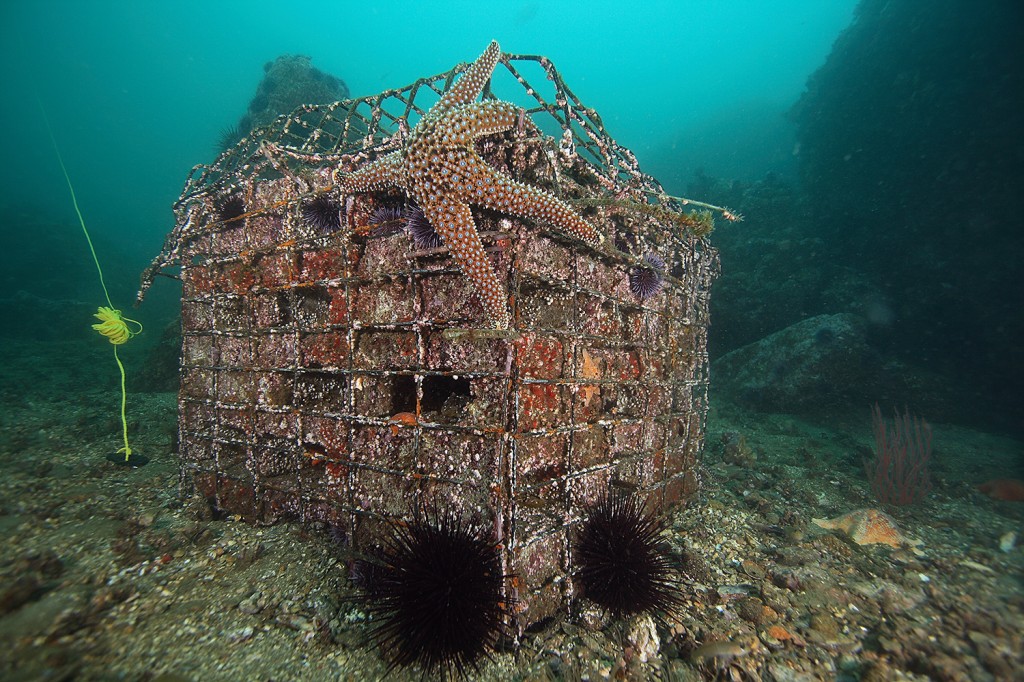

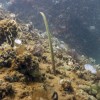

Scott also showed me how to build the coral settlement devices that they’ll use to study growth in the harbor. They consist of two brick tiles screwed into a metal rod, anchored with a lead weight. Larval coral settles between the tiles and the devices can be removed for measurement and study. For this I had to first assemble and then use a tile saw, as well as break out the power drill and masonry bit. Rest assured, I wore my safety goggles

I also had the exciting opportunity to tag along with Retired US Navy Commander Mike Freeman, the former commanding officer of the Navy’s Mobile Diving and Salvage Unit One (MDSU1) and current Harbor Pilot as he and his crew piloted a huge container ship out of the harbor and a naval submarine back in using two tugboats. Stan and NOAA Archaeologist Kelly Gleason joined us for the ride. We pulled up along the Maersk Peary, which distributes fuel among naval bases, and the tugs turned her into the crowded harbor and guided her into the open sea. Stan pointed out various historic and current aspects of the harbor, and as we came out into the ocean we had a great view of Waikiki and Diamond Head Crater. I even got to drive the tug back toward the harbor, and we then met up with the sleek, sharklike black sub (for national security reasons I’m not at liberty to say which one). It had been out on exercises and was coming in briefly to switch personnel and get more supplies, first and foremost about a dozen five-gallon drums of ice cream. The sub headed back out to sea and we returned to the base. Definitely a unique experience!

By the end of the week the park was given the green light to dive, and we prepared for the main activity of my stay: diving the USS Arizona. This was a once in a lifetime opportunity, since only National Park Service or Navy divers may dive here. I would join Scott for a routine dive to check and maintain the buoys at the bow and stern, monitor some cracks in the hull, and collect any trash that visitors had dropped from the memorial. There are also ongoing scientific projects to map the wreck and study rates of corrosion, monitor the oil that continues to leak from the ship, and study the surrounding marine ecosystem and harbor as comparable to a protected area, including the coral settlement study I had helped prepare.

Scott first took me on a few proficiency dives on Oahu’s north shore (which lacks its famous surfer-attracting waves during the summer months) so I could get used to the full-face mask we would use in the harbor. Visibility is low in the harbor and getting disorientated on the wreck is always a risk, so it’s safer to be able to talk to one another via the microphone systems in the masks. More importantly the full-face mask protects us from any oil or other carcinogens in the water leaking from the USS Arizona. We dove in protected areas, full of fish, and saw a few turtles and a retreating shark. It took me a while to get the mask to fit, but once it was set I found it very comfortable to have so much of my face dry underwater. Scott also took me to the USS Arizona memorial to orient me, and showed me where we would put together our gear and enter the water, as well as the buoys and features of the wreck visible from the memorial. I had been to the memorial once before a few years earlier, and it was no less moving the second time around to be reminded of the history of the place and be surrounded by visitors paying their respects to the fallen sailors below.

On the day of our dive, we drove our gear and tanks to the memorial and loaded them on the same ferry that takes visitors out to the memorial. Fortunately it wasn’t a terribly busy day—the park gets 1.8 million visitors each year, so the ferries can get jam-packed, leaving little room for dive gear. On the memorial dock, we brought our gear to an out of the way corner to set up. We waited for everyone to go from the boat into the memorial, the returning crowd to go from the memorial into the boat, and for the boat to take off. We then had a few-minute window before the next boat came into view to quickly change into our wetsuits in hopes of avoiding too many pictures of or visitors upset by the bathing suit-clad National Park Service workers. We donned our scuba gear as curious visitors craned around from the memorial to see what we were doing. A kindly WWII veteran thanked us for our work and wished us a good dive as his family wheeled him up the ramp, and with that blessing we were ready to roll into the harbor.

We swam over to the wreck and descended into the murky green water. I’d known this dive would be on my schedule since early June and had thought a lot about how to approach it, unsure how I would feel to be diving at a site that is the tomb of over a thousand Navy sailors, and represents the sacrifices and loss of thousands more. As features of the ship’s hull came into view, I was reassured by a sense of peacefulness. The wreck is covered in soft sponges and delicately swaying feather worms, everything quiet under the water. Scott pointed out both ecological and historical features of the wreck as we swam along the hull to the buoy at the stern. They’re trying a new strategy to protect the buoys from encrusting organisms and the oil that continuously leaks from the wreck: wrapping them in saran wrap. So far it’s proving effective. We continued along the starboard side, and Scott pointed out the intact guns of turret no. 1, which were long thought to have been salvaged but the Submerged Resources Center discovered in the early 1980s when they initially mapped the wreck. We then moved into the blast zone. Here the violence of the explosion was apparent in metal twisted beyond recognition, everything confused and mangled. Having been surrounded by such young Navy faces at the base and recently dropped off my eighteen-year-old brother at college made it especially sobering to consider the 1,177 lives cut short here seventy years ago.

After inspecting the bow buoy, we did a quick sweep underneath the memorial for anything visitors had accidently dropped. All we found was a pair of sunglasses already coated in coralline algae, although Scott tells me the record is four iPhones on a single dive. We broke down our gear and caught the last ferry back to the base along with the final load of visitors who had come to pay their respects that day. I’ve felt somber and reflective after diving before, generally about the state of the ecosystem, but never before had I emerged from a dive so grateful to be alive and have my family intact.

Scott was kind enough to give up his Saturday for me, and took me for another dive on the USS Utah. The Utah was a training ship, and one of the first hit during the attack on Pearl Harbor. She lies canted on one side where she was moored near Ford Island. The Utah isn’t as heavily visited as the Arizona, so our preparation and entry were much more relaxed, save for one delighted little boy who exuberantly pointed us out to his family. The Utah was also hushed and serene, and had more recognizable features: a ladder here, a hatch there. Since this wreck is in a more remote location and not constantly staffed, there have been some problems with fishing and looting. Scott and I got tangled up in an abandoned fishing line early in the dive, and Scott pointed out a silver handle that had recently been stolen off the wreck. He told me that they’ve even had problems with theft of the ashes of the survivors who request to be interred with their shipmates. I was astonished that someone could be so disrespectful. We ended the day with some beautiful snorkeling on the north shore and a delicious visit to the famous Poke Stop.

My heartfelt thanks to Stan for all his expertise on Pearl Harbor, Mike for taking me out on the tugboat, and Scott for taking such care to provide me a varied and rich experience here, as well as to our veterans and the men and women serving our country.

Kirsten Grorud-Colvert, the lead scientist on the project, and I were dropped off at each buoy while the boat circled around waiting for us to complete the task. With me carrying the BINCKE, and Kirsten carrying the replacement SMURF, we approached the buoy.

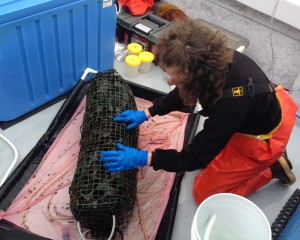

Kirsten Grorud-Colvert, the lead scientist on the project, and I were dropped off at each buoy while the boat circled around waiting for us to complete the task. With me carrying the BINCKE, and Kirsten carrying the replacement SMURF, we approached the buoy. I waited for Kirsten to unclip the SMURF from the mooring line and replace it with the new SMURF. As soon as she unclipped the old SMURF I scooped it into the BINCKE and we signaled for the boat to come back and pick us up.

I waited for Kirsten to unclip the SMURF from the mooring line and replace it with the new SMURF. As soon as she unclipped the old SMURF I scooped it into the BINCKE and we signaled for the boat to come back and pick us up.

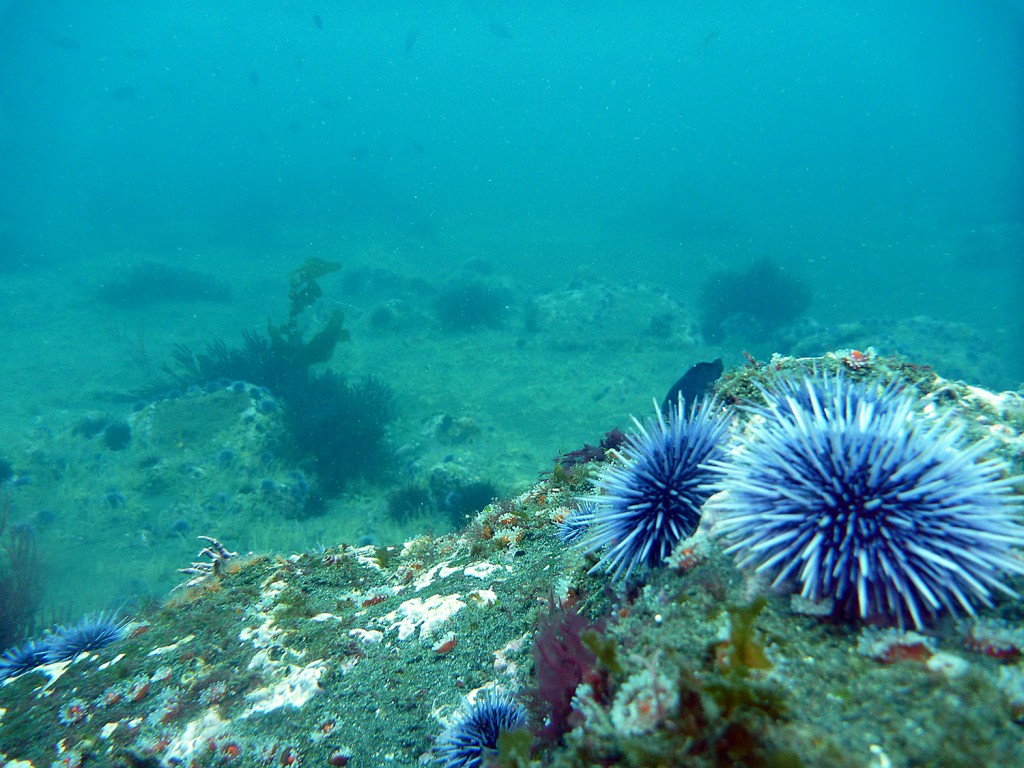

The fish were collected, and stored in individually labeled bags, which were kept on ice for transport back to the lab. The information gathered from SMURFs provides insight about settling patterns in early life stages for many nearshore fish species. This information is essential for effect marine conservation management, and will also act as a platform for educational outreach about the early life stages of marine organisms. As an efficient and low-cost method for sampling this type of information, it is hoped that SMURFs will become prevalent in large-scale monitoring projects throughout the west coast.

The fish were collected, and stored in individually labeled bags, which were kept on ice for transport back to the lab. The information gathered from SMURFs provides insight about settling patterns in early life stages for many nearshore fish species. This information is essential for effect marine conservation management, and will also act as a platform for educational outreach about the early life stages of marine organisms. As an efficient and low-cost method for sampling this type of information, it is hoped that SMURFs will become prevalent in large-scale monitoring projects throughout the west coast.