My last stop this summer took me to Washington DC to culminate my internship by experiencing the National Park Service (NPS) from the standpoint of national policy-making. I left Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) one week into my new job for a visit to the big city–excited and nervous to spend 5 days in our nation’s capital. I visited DC once before, for a few days of intense museum-going. On this trip, my days would be filled with meetings at NPS headquarters, National Geographic, and the Smithsonian. It doesn’t get any better!

I arrived to absolutely fantastic weather in DC. After settling in to my hotel, I took the afternoon to re-visit my favorite museum in the city, the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (of course) and take a walk along the National Mall. As evening fell, I took some night shots at the Washington Monument and National WWII Memorial. Unfortunately the Reflecting Pool was closed for reconstruction, so I couldn’t photograph that iconic view towards the Lincoln Memorial. The Washington Monument was still closed due to damages from the earthquake earlier in the year too, but it and all the other monuments along the National Mall were quite impressive flooded with light at night and made for fun photographing.

The next day, I headed to National Geographic to meet with photo editor Todd James who graciously agreed to meet with me and show me around. First we headed down to the engineering department to see some of the innovative ways that engineers and photographers team up to capture previously impossible images using new technology. After a tour of Nat Geo’s buildings and a look through the new photography exhibit by Brian Skerry, one of my favorite underwater photographers (the exhibit is called Ocean Soul, I highly recommend it if you are in the area: http://events.nationalgeographic.com/events/exhibits/2011/10/05/ocean-soul/), we went back to Todd’s office where he gave me an inside look at his job as a photo editor for the magazine. From project proposals, to research, to sorting through tens of thousands of images, the job of a photo editor requires a diverse knowledge base and an aesthetic eye. I gained a much greater appreciation for the process through which photos end up on the pages of National Geographic. Like every other photographer, I dream of having my own images printed in this magazine someday, so it was extremely valuable to gain an inside perspective of the process. Todd was so generous with his time and answered all my questions with patience. Additionally, he was kind enough to review some of my images from this summer and offered some very encouraging and helpful advice for my portfolio development.

The following day was my big debut at NPS headquarters. I met up with Cliff McCreedy, Marine Resource Management Specialist in the Ocean and Coastal Resources Branch of the Water Resources Division. Cliff had scheduled a meeting for us at the Department of the Interior (DOI), but first, we set up a presentation I made for a lunchtime talk in one of the conference rooms, where I met Jonathan Putnam, International Cooperation Specialist for the NPS Office of International Affairs (http://www.nps.gov/oia/). Did you know that the NPS participates in international collaborations to aid in the creation and management of national parks around the world? I didn’t, but it just makes NPS that much more amazing to me!

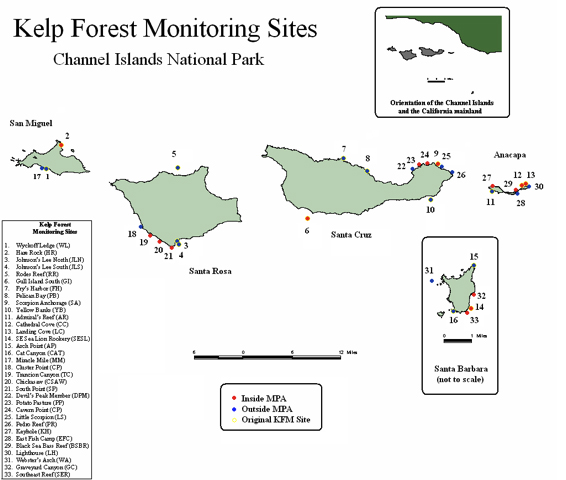

Before we headed to the DOI, Cliff gave me an overview of the recent history of marine and aquatic natural resource management in the NPS. While active management of our marine and coastal resources has always been an official part of the National Park Service’s mandate, it was not until in the mid-2000s when increased management concerns led to the creation of a specific branch of the NPS dedicated solely to this purpose in the arena of marine and coastal natural resources. Much of the credit for establishing the Ocean and Coastal Resources Branch can be given to Gary Davis, who was instrumental in the formation of the Kelp Forest Monitoring Program at Channel Islands National Park. A marine ecologist, Gary understood the importance of establishing baseline knowledge of the ecological communities within the submerged lands of our parks, and long-term monitoring to study the health of these communities, and designed the national ocean program around those two foci.

Cliff and I headed to the DOI, a big, intimidating, granite building, and met up with Dr. Marcy Rockman, Climate Change Adaptation Coordinator for Cultural Resources, who would join us for this meeting. We went inside and met up with Dr. Stephanie Toothman, Associate Director for Cultural Resources, and Julia Washburn, Associate Director for Interpretation and Education, and all three women introduced themselves and their roles within the NPS. I can’t tell you how inspiring it was to meet these three incredibly successful and influential women who are working for the common good, really applying their talents, experience, and education towards a cause that is beneficial to everyone—preserving our heritage.

I shared my experiences from this summer, and discussed all of the incredible work being done by dive teams in the parks I visited. After the meeting, we quickly left the DOI and returned to NPS headquarters, and walked right in to a nearly full conference room! By the time everyone came in and got settled, there were at least 15 people from all different branches of the NPS (Interpretation, Cultural Resources, Natural Resources, Dive Safety, International Affairs, etc.) who had come to hear me share my experience this summer. I had put together a presentation with lots of photos, and talked about my personal highlights as well as the important conservation and preservation stories I learned in each of the parks, like the uphill battle against lionfish invasion in south Florida, or the incredible success of the Kelp Forest Monitoring Program in the Channel Islands. My audience was great, and I was so happy to meet several of them personally afterwards.

We had a chance to meet briefly with Beth Johnson, Deputy Associate Director for Natural Resource Stewardship and Science, as well. She was so friendly and heavily encouraged me to pursue work within the NPS – although it is not really something I need to be convinced of, I would be thrilled to work with NPS! I will be scanning the pages of usajobs.gov religiously from now on, that’s for sure!

The following day I had the chance to meet up with Anya Watson, 2005 Our World-Underwater Scholarship Society North American Rolex Scholar. She is currently working as a Dive Officer for the Smithsonian Scientific Diving Program, which coordinates staff divers in Smithsonian research and education projects around the world. She gave me a tour of the new Sant Ocean Hall at the National Museum of Natural History, and then we went to the National Museum of American History where we perused some of the maritime history exhibits and Anya showed me some of her favorites in the museum’s collection. She also showed me the dive locker, which is oddly enough on a lower level surrounded by paleontological specimens, like dinosaur bones!

Thank you so much to everyone who was so generous with their time this week—Todd James, Cliff McCreedy, Jonathan Putnam, Stephanie Toothman , Julia Washburn, Marcy Rockman, Beth Johnson, and Anya Watson, and everyone who took time out of their busy day to attend my lunchtime talk at the National Park Service!

After three months, I can’t believe my internship is ending. I already can see that this opportunity has irrevocably changed my life; and I am so excited to see how it all plays out. When I first decided to leave Mexico, I had no idea what lay ahead, if I would be able to find a job, apprehensive that I might end up somewhere I didn’t want to be, doing something I didn’t love. Thankfully, the opposite of that is true—this internship directly led me to my new job at WHOI, and a new life (at least for the next few months) in a place I love. I am so thankful to have reacquainted myself with the United States and explored so many potential new homes for the future, and to have created a network of friends and professional contacts on both coasts.

As I have known since the beginning of this internship, while the resources that the NPS works so hard to preserve are irreplaceable and wondrous, the true gem is the group of people tasked with protecting the future of these precious sites and resources. We have entrusted them with our heritage, and they work harder than any other group of people I have ever known to make the American people proud of that heritage. I am beyond proud to have worked with the National Park Service, and hope to continue to working with NPS in the future—I still have so much to learn, experience, and contribute in our National Parks!