Going into the internship, I knew that many OWUSS NPS interns get the opportunity to present their whirlwind adventures in learning and diving to various NPS Associate and Deputy Directors at the Department of Interior office in Washington, DC. Of course, this means that the presentation is typically scheduled as the last Hoorah – the final destination once an intern has collected their share of experience, memories, perspective, and photographs from parks across the country.

To say that this week crept up on me is a bit of an understatement, and I found myself having to do a double-take once landing in DC. This can’t really be ‘the end,’… can it? I’m just getting good at this! After five or so consecutive weeks (and many months prior) of park hopping, flinging myself into new field teams, new states, and new environments, I am here now, swapping my well-worn NPS SRC field shirt for an ironed button-up, ready to show off the NPS Dive Program to decision makers who hold the future of this program in their hands.

Lincoln Memorial, National Mall, Washington, D.C.

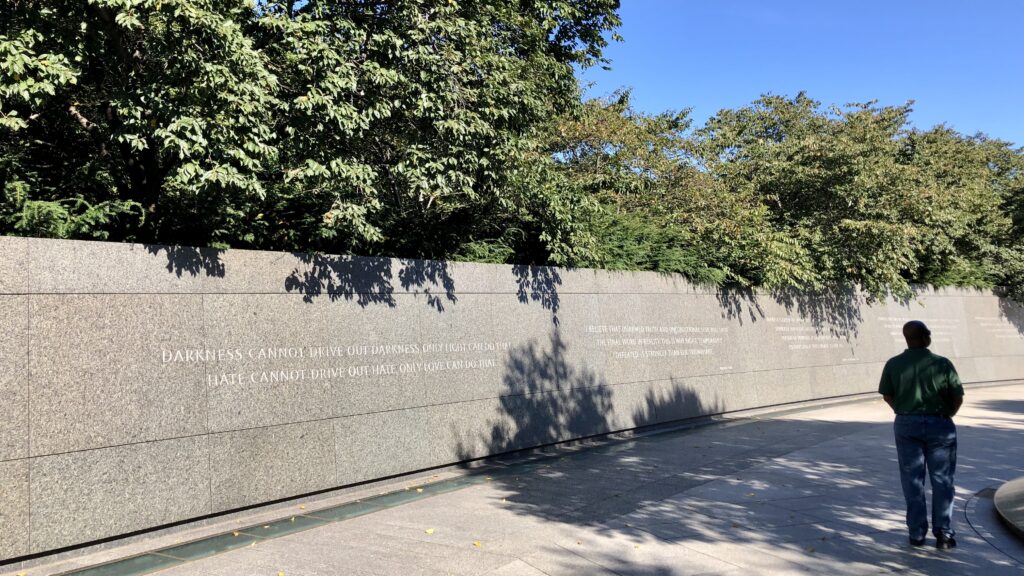

I ease into the week with some sightseeing, having never visited Washington, DC, before. With the generous help and friendly company of Daryl Avery, NPS Branch Chief for Occupational Safety and Health, together, we walk through the National Mall and Memorial Parks – home to the country’s most iconic monuments commemorating historical events that shaped the nation. While the monuments can be appreciated by any passerby (and details read via interpretive signage or a quick Google search), they truly come to life with the help of Interpretive Rangers placed throughout the National Mall grounds. I was grateful to encounter many knowledgeable Rangers who shed light on the history of these significant events and individuals and their architectural design and construction – revealing small details one would likely miss without a trained eye. An educational and enjoyable day for myself and Daryl (featuring a delicious meal at the iconic Old Ebbitt Grill) and an excellent orientation to the city center, during which I noted additional points of interest to visit during downtime throughout the week.

WWII Memorial, National Mall. Interpretive Ranger Adam Cochran provides an excellent overview of each detail of the monument, greatly enhancing my visit.

View from the top of the Washington Monument, National Mall.

Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, National Mall. Powerful quotes line the walls – Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.

Korean War Veterans Memorial, National Mall.

The following day, I grab a hearty breakfast, settle into my new accommodations, and do one last presentation run-through before heading to the Department of Interior office to meet with Daryl and Michael May, NPS Chief of Office of Risk Management. After filing through security, affixing the necessary visitors pass to my collar, and a short tour of the facilities (including a beautiful display of artwork lining the halls – often attracting tourist groups), it comes time to do what I was brought here for… and I eagerly await the opportunity to share my experience with the NPS Executive team.

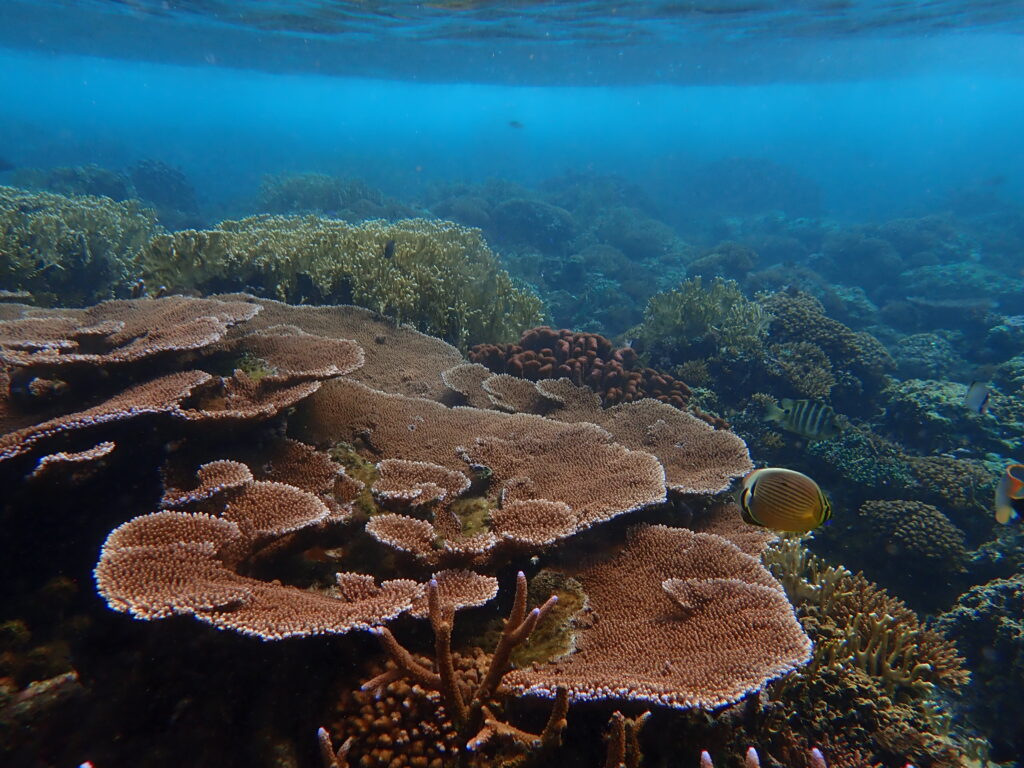

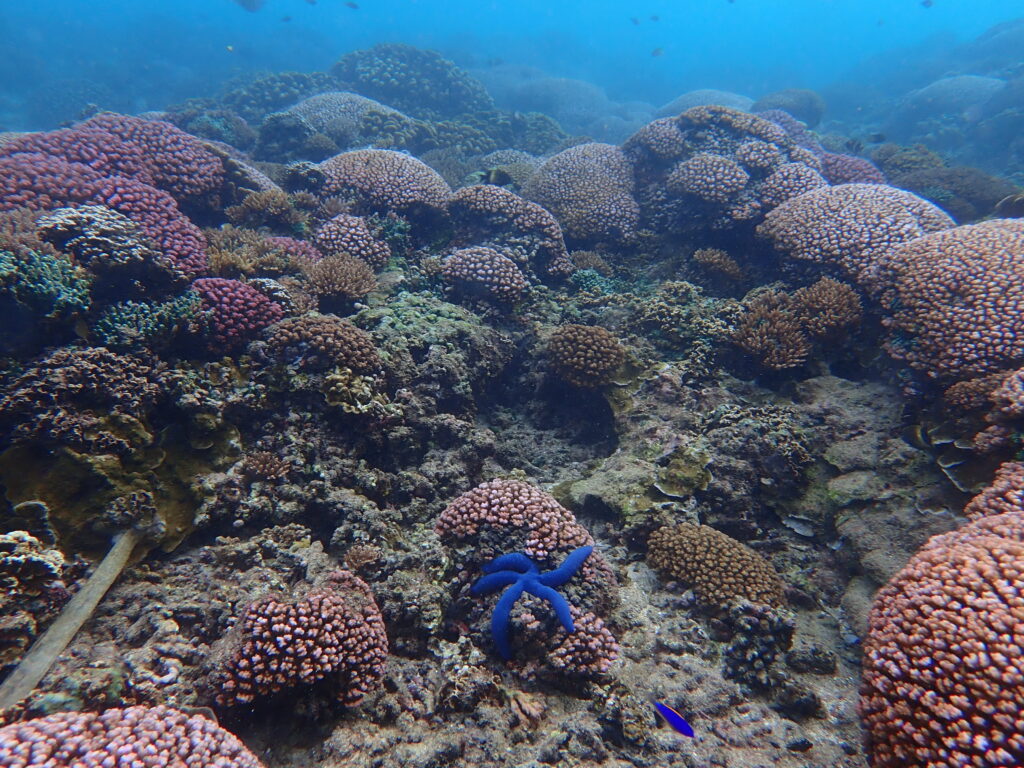

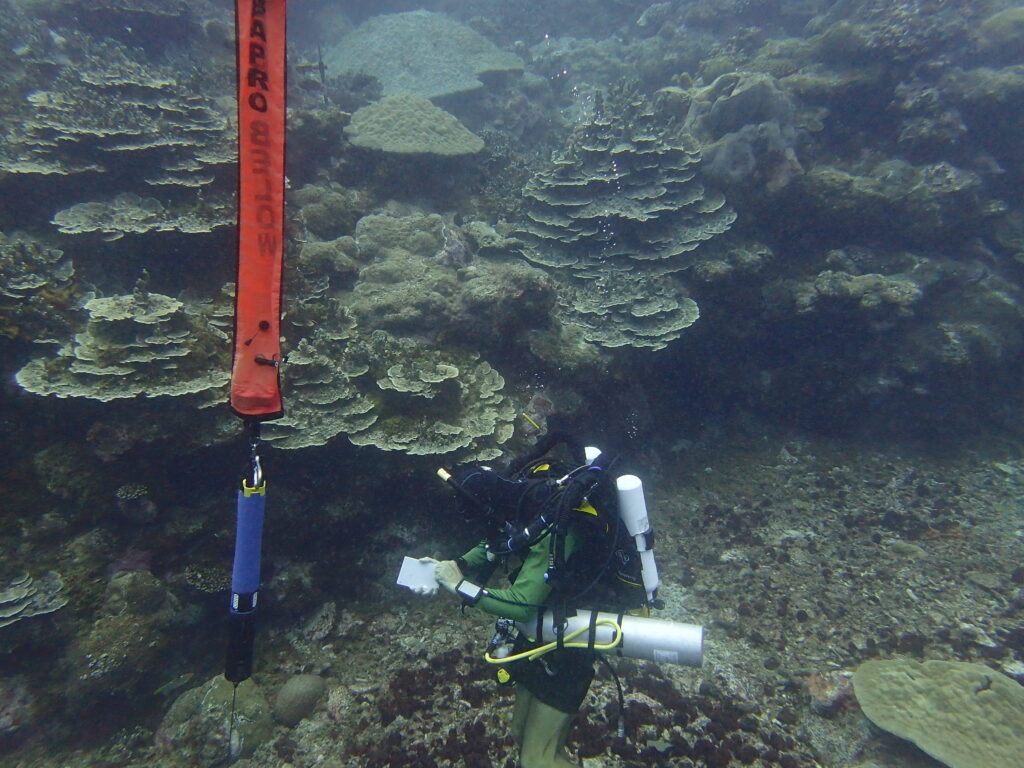

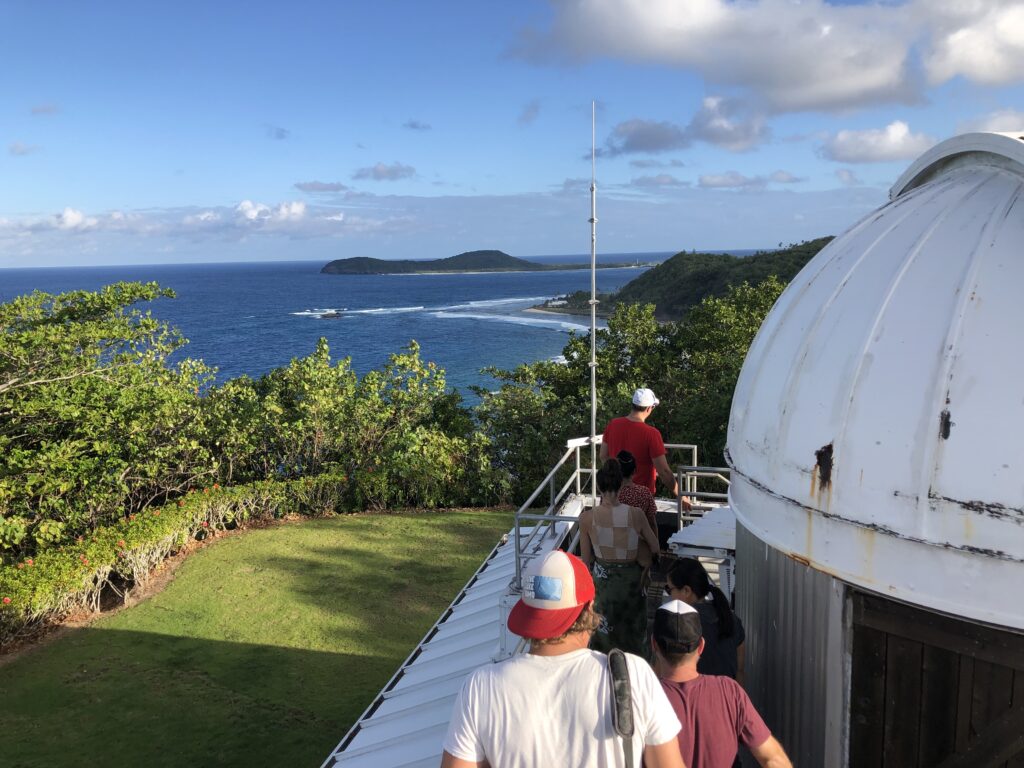

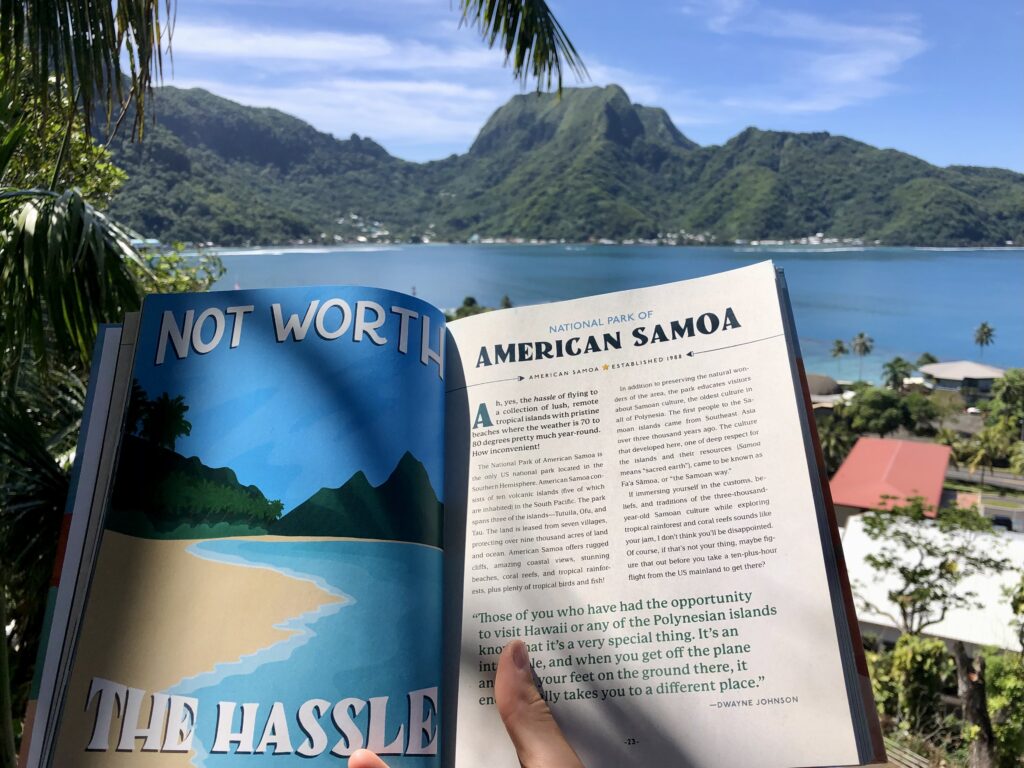

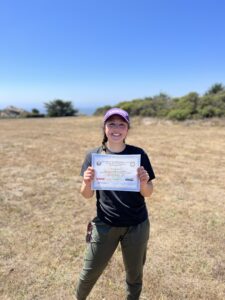

A 30-minute presentation passes quickly in a small board room, flipping through slide after slide of NPS Dive Program highlights, history, project goals, and accomplishments. Presenting to both divers and non-divers alike, I am relieved to see many encouraging nods and note-writing in the crowd, leading to positive feedback and curious questions in the discussion that follows. While preparing this presentation, I was taken aback by the fact that across 23 NPS dive programs (and 120 individual divers), over 6,500 dives were conducted in 2021 alone. Across seven National Parks, I worked directly with over 40 NPS divers, speaking to the scope of experience that interns gain in such a short timeframe. Bringing fresh eyes, a global perspective, curiosity, a strong diving foundation, and an eagerness to experience applied science, diving, and monitoring outside of academia, I gained a holistic perspective of the NPS dive program. I can honestly say that the multidisciplinary scope and rigorous safety protocols are unmatched by any other dive program or team I have previously been a part of.

A trip to DC would not be complete without visiting several of the impressive museums (often free for visitors), and as such, I filled my spare time with trips to the Museum of Natural History and the National Museum of African American History & Culture. Acknowledging that it is possible to spend multiple days at each museum, I found myself returning to the National Museum of African American History & Culture on several occasions, opting to focus each visit floor by floor (organized in temporal increments from 1400 to the present day), making for a more comprehensive and impactful experience. During the week, I also had the opportunity to meet several NOAA Ocean Exploration employees, including Jeremy Weirich, Director, and Adrienne Copeland, PhD, Grants Program Manager, further enriching my experience in the nation’s capital.

The National Museum of African American History & Culture

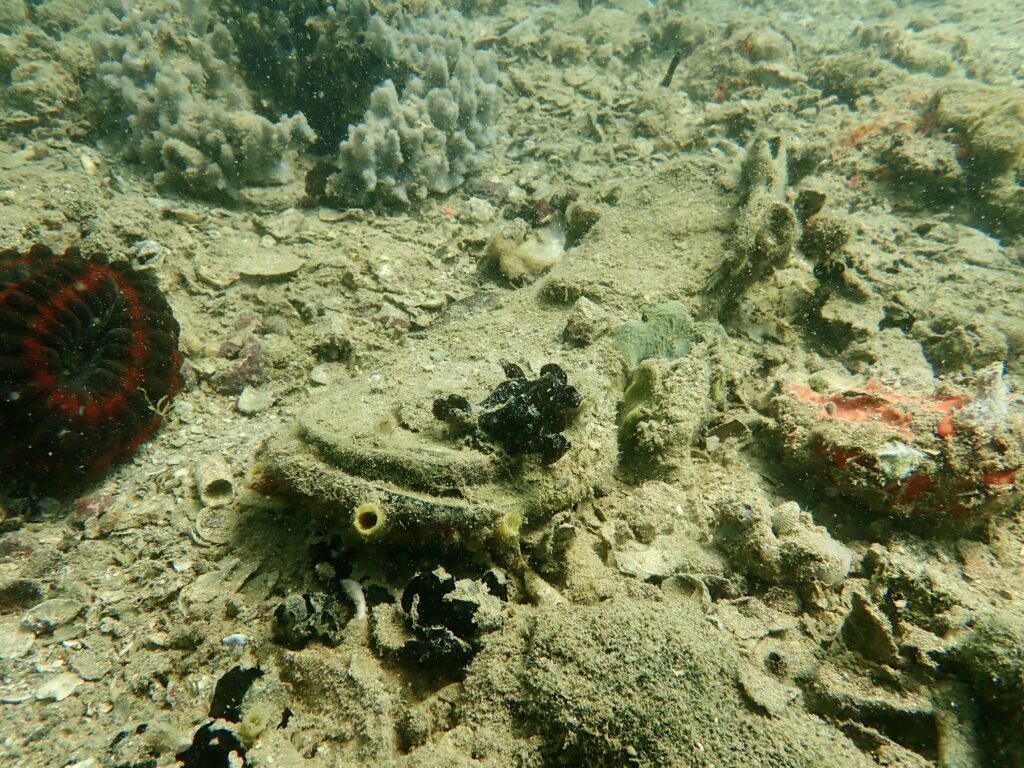

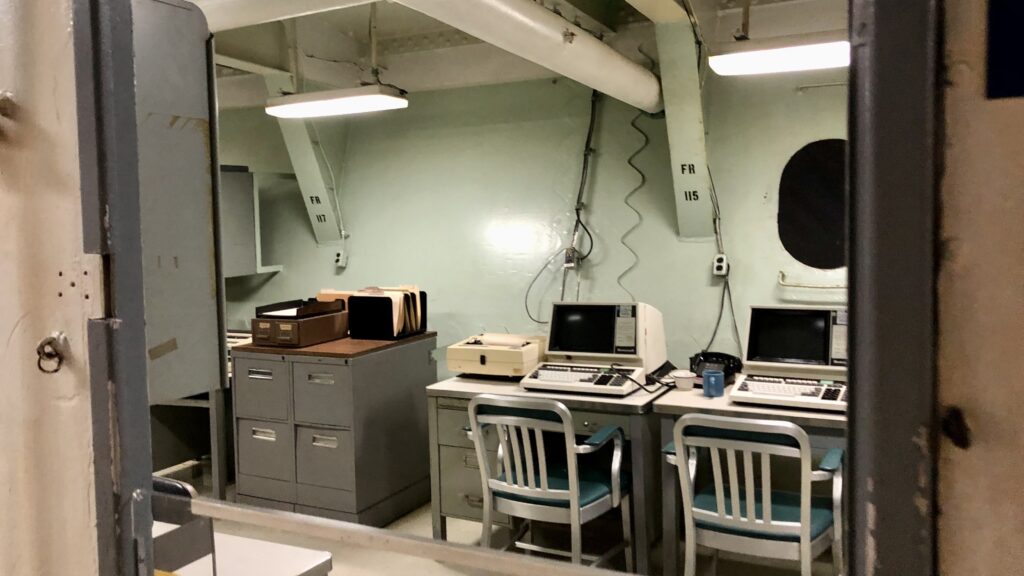

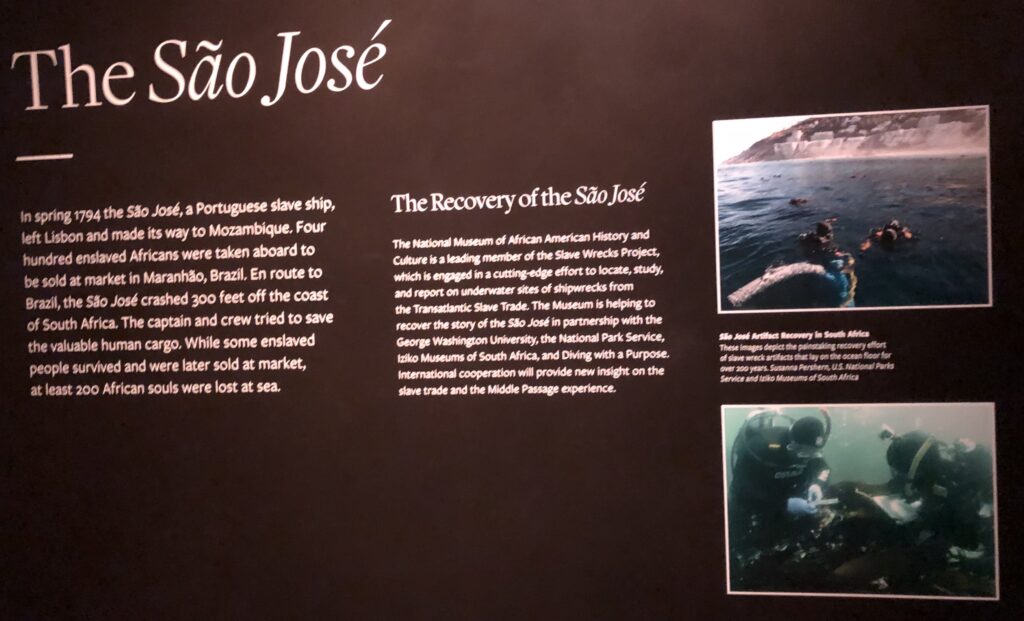

Inside the National Museum of African American History & Culture. NPS Submerged Resources Center played an instrumental role in uncovering the remains of the Sao Jose (a Portuguese slave ship), in collaboration with Diving with a Purpose, George Washington University, and Iziko Museums of South Africa.

Museum of Natural History, Oceans Hall

Museum of Natural History

Reflecting on my experiences thus far, I feel empowered. Seeing first-hand the resources dedicated to underwater exploration and monitoring gives me hope – for education, preservation, and understanding of the underwater world, which makes up 70% of our planet. I am proud to stand in DC, representing the NPS Dive Program and sharing just a small glimpse into the work they do. As my time in Washington, DC, comes to a close, I am relieved that it is not yet the final chapter of my internship. Drawing on international connections and collaborating with underwater archeology teams around the globe, the NPS SRC team has connected me with Parks Canada for one last project. I am incredibly excited to represent NPS on my home turf in a few short days. Stay tuned as the OWUSS NPS intern goes international!

Thank you Daryl Avery (and Michael May) for hosting me in DC