Dry Tortugas National Park

Before this summer, I never imagined that I would be waking up on a ship heading to a 19th century fort in a remote island paradise. A couple weeks ago, that was my reality when I traveled with the South Florida Caribbean Network to Dry Tortugas National Park for 10 days of coral reef monitoring. Located 70 miles west of Key West, FL, Dry Tortugas National Park (DRTO) is an 100 square mile park that mostly open ocean, consisting of less than 1% land. On one of its few islands lies the Fort Jefferson, the largest masonry structure in the western hemisphere (composed of more than 16 million bricks!). Initially designed as a defensive outpost to gain control of important waterways in the area (Gulf of Mexico, Straits of Florida), work on the fort faltered during the American Civil War. It was then repurposed into a military prison, where it held unlucky prisoners in a hot, brick oven of a fort (famous prisoners include four charged crimes associated with the assassination of President Lincoln), and then later served as a coaling station for coal-fueled U.S. ships.

Inside Fort Jefferson

Along with a storied land-based history, DRTO is also peppered with maritime history. Located in the center of a maritime highway and surrounded by large fringe reefs, barely submerged shoals, shifting tides and strong currents, the ocean surrounding the fort is a navigational nightmare for early sailors. Due to these treacherous conditions, the waters surrounding the fort are home to hundreds of shipwrecks, the most submerged resources of any park unit. However, we weren’t here for the archaeological sites that exist within the park boundaries. We were here for the coral reefs.

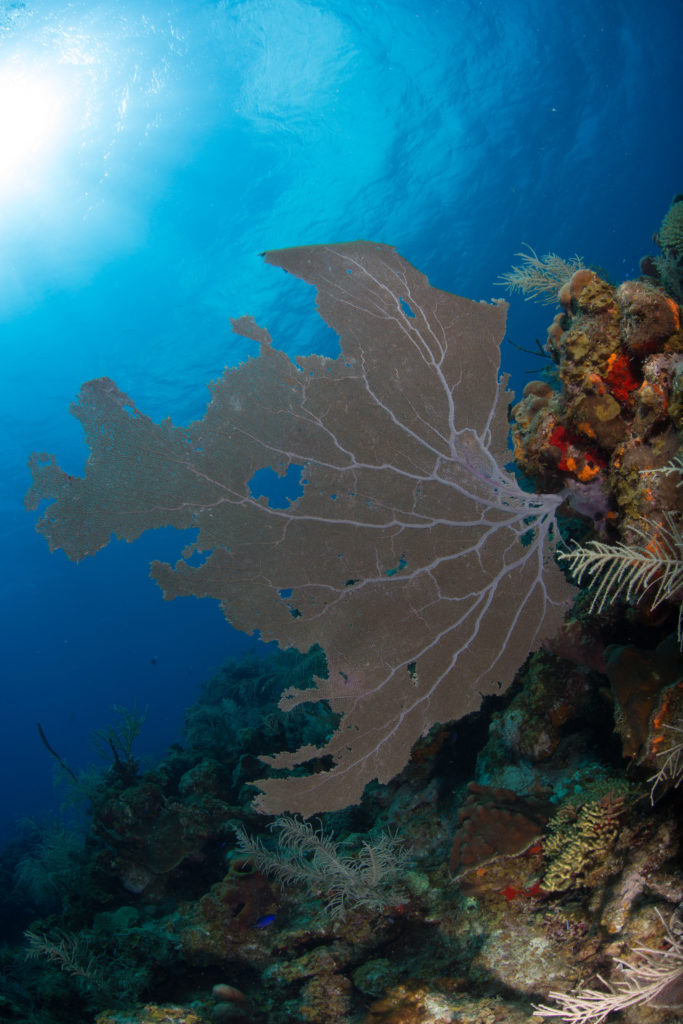

Dry Tortugas is home to some spectacular coral reefs

The South Florida and Caribbean Network (SFCN) is part of the Parks Service’s Inventory and Monitoring network – part of the NPS that is in charge of gathering and analyzing information on the natural resources that exist in park boundaries. SFCN covers the marine side of the South Florida and Caribbean parks, an area in which one of the most biologically critical natural resources is the coral reef. DRTO is home to some of the finest reefs in Florida, unlike ones anywhere else in the Keys. Far from any cities or towns, these reefs have been relatively free from degradation by human influences and are in much better shape than many of their near-shore cousins. The reefs here also consist of a reef terrace habitat: a uniquely flat and uniform plate-like floor of corals, caused by lower-light conditions at deeper depths, creating a huge flat plateau of coral growth up to five feet off the sea floor.

Centuries worth of old coral skeletons lie underneath the exposed surface area

To top things off, these reefs make for ideal fish habitat with their high level of structural complexity hidden in the 5 feet of coral-made structure under their biological roof. The DRTO reefs make up some crucial spawning grounds for certain species of reef fish, due to a mix of ideal habitat and currents and retention gyres working to keep fish around. Furthermore, these reef’s larval supply gets caught up in currents and sent towards South Florida, working to replenish their more heavily impacted reefs. This oceanic linkage was discovered earlier and then protected in 2001, creating a positive response from overfishing after the fact – a conservation success story.

All these conditions make the reefs at Dry Tortugas a pretty special spot- a haven for threatened corals and overharvested reef fish, where they have a slight break from the onslaught of perils sent their way. However, they aren’t safe from everything. Like most of the rest of South Florida and Caribbean reefs, coral disease has made an appearance in DRTO. First noticed on their reefs by NPS researchers in 2008, coral disease (primarily chronic white plague out on these reefs) has had variable prevalence but is becoming more persistent – 2016 and 2018 were especially bad years. In the past 5 years, the SFCN team has noticed around an average of 30% disease-related coral loss at their monitoring sites – especially bad news when coral cover has been on a steady decline since 1979. The disease kills off corals and then sloughs off their tissue, leaving a freshly exposed white skeleton. This quickly gets overgrown by turf algae, which then inhibits growth by new corals.

Close-up on diseased coral – the stark white skeleton is freshly deceased, while the brown turf algae encroaching from the corner dictates less recent mortality

The SFCN team works to monitor and report on the state of these reefs to see how they react in response to events like disease outbreaks and bleaching. They’ve been surveying these reefs since before disease reached the Dry Tortugas, making their surveys crucial resources for understanding how these plagues start and spread. I was lucky enough to tag along to see how it all worked.

The M/V Fort Jefferson from in the water

During our time out at DRTO, we stayed on the Motor Vessel Fort Jefferson, the 110-ft vessel serving as a transport boat, research vessel, dive support, as well as any other needs the park may have. While staying on a boat may seem like meager lodging, the M/V Fort Jefferson was far from it. Decked out with a full kitchen, bathrooms, bunks and living area, this was a veritable floating hotel – the only thing it was missing was Wi-Fi. I was here with four marine biologists and ecologists of the SFCN team: Mike Feeley, Rob Waara, Jeff Miller, and Lee Richter, as well as two of their research interns: Steph Topal and Morgan Wagner from University of Miami. Also on board was the Ft. Jefferson’s incredible crew: Captain Tim, Mikey Kent, and Brian Lariviere.

-

-

The M/V Fort Jefferson itself

-

-

Complete with a full kitchen and washer/dryer, this vessel has pretty much all the amenities you’d need

-

-

The ship’s common area

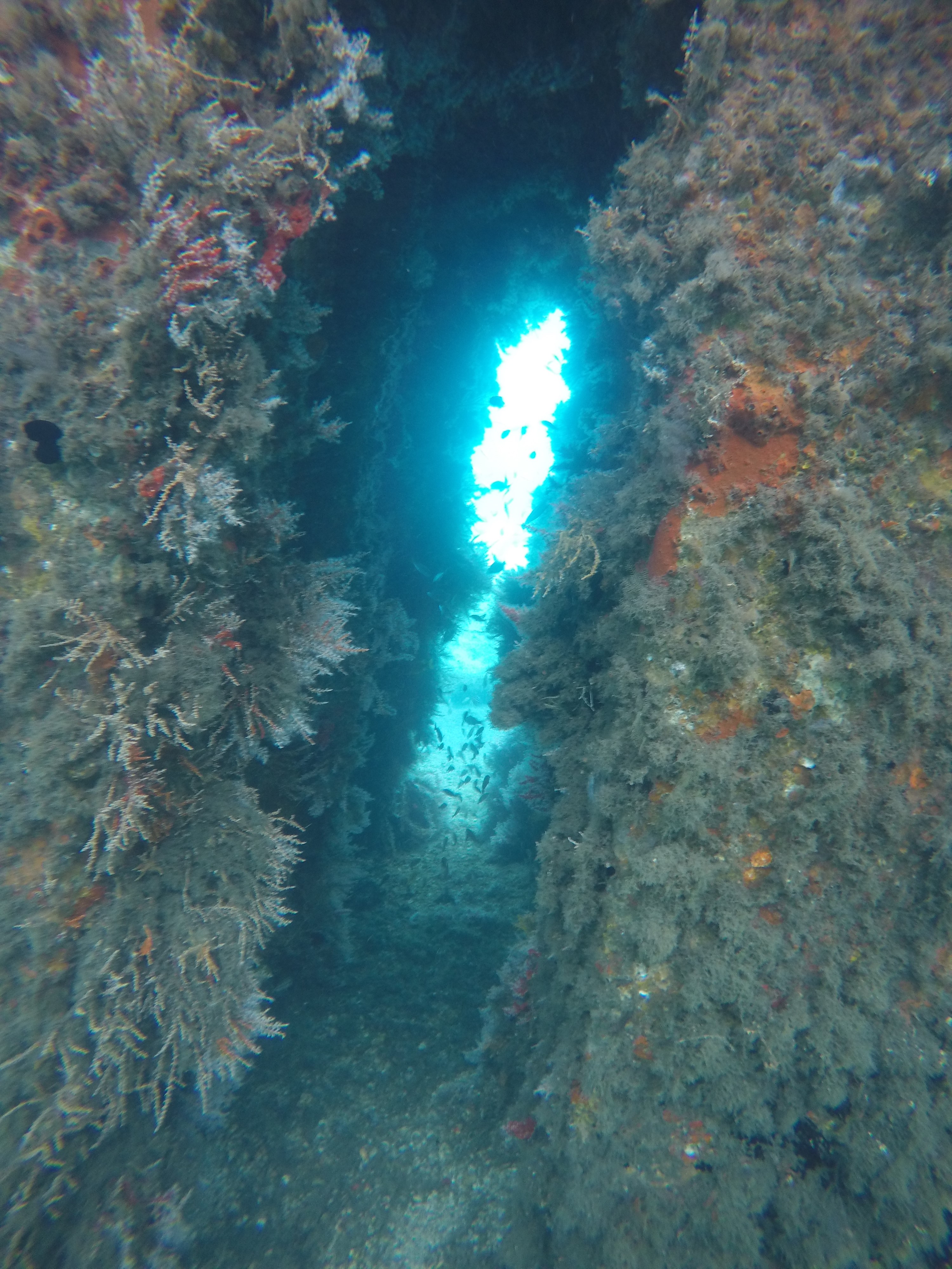

Upon arrival at the Fort, we immediately went to work. With a full trip of benthic monitoring and temperature logger collecting ahead of us, there was no time to waste. Shortly after the arrival of our floating hotel to Garden Key, home of the Fort Jefferson (the brick one, not the vessel), we gathered up our dive gear and headed out on the 27-foot SFCN vessel, the Twin Vee. The first day’s work was easy enough – go to the first benthic monitoring site and set a mooring for our work for the rest of the week, as well as to conduct a quick shakeout dive to reacquaint everyone with their gear and the ocean. The first monitoring site is at a spot called Bird Key – a highly rugose reef that was one of SFCN’s initial survey spots in the area, as well as the first spot that disease was a serious issue. Not much disease persists here anymore, but its impacts are still obvious: coral cover has dropped in response to around 8-12%, potentially only leaving the few resistant ones remaining. During our shakeout we had a brief chance to explore – the reef was peppered with small canyons reaching down to the sand, one with a small swim-through, making for fun diving. I was excited to spend the next couple days here, exploring more of what the site had to offer.

-

-

A small canyon on the reefs at Bird Key

-

-

Large coral head on Bird Key reefs

-

-

High relief and good structure makes for fun diving

On our return to Garden Key, I had a chance to check out something that I’d been thinking about ever since reading the blogs of past OWUSS NPS interns. Living underneath the M/V Fort Jefferson and the docks it moors up to are at least three goliath groupers, groups of tarpon, and tons of baitfish. I was eager to go spend some time amongst the fishy masses so pretty much as soon as we returned from our dive I grabbed my camera and jumped in. The density of biological life in such a small location was really thrilling – I’d dive through a thick cloud of fish to reach clearings with slowly patrolling tarpon, pretending to be ever uninterested in their tasty prey that swirls around them constantly, and then swim a little deeper to be met with the gigantic face of a 500 lb goliath grouper (or two, if you’re lucky). Having this much action right underneath your housing was pretty unbelievably convenient, so I stayed in the mix until the sun set and I didn’t have enough light to see in the dim underbelly of the docks. Ending my first day at DRTO swimming with hundreds of fish had me thinking it couldn’t get any better, but I sure was wrong.

The next day we started work in earnest: benthic reef monitoring at the Bird Key sites. This monitoring requires two teams. The first one, the recon team, is in charge of finding preset pins (big 1-foot metal spikes) nailed into the reef and running a transect tape between the two for the second team, the survey team, to survey. This recon team sounds like it has a pretty easy task, and it would be if it weren’t for the tenacity of life underwater. In a marine environment, things grow fast and they grow wherever they can. This makes locating metal pins rather difficult, as they quickly get overgrown with algae, sponges, hydroids and tunicates which make them seem to melt into the surrounding reef. To complicate things even further, the structure and life of the surrounding reef changes as well, which can work to obscure any obvious landmarks used to locate the pins in previous years. At the Bird Key site the transect locations are not particularly close to each other – to find one, you must start at the previous one, then follow a certain compass bearing for a set distance. At this point you have to start searching for an almost certainly overgrown metal pin that can be sticking out anywhere from 10 cm to 1ft out of the reef. The SFCN team has laminated maps of sorts – with compass bearings and distances listed from one transects to another, as well as with pictures of obvious landmarks to use when locating points – but that only helps so much. A careful eye is a necessity in this type of work. And of course, when one pin is found, the work isn’t over yet. Then you have to begin the whole process over again to find the second pin to end the transect itself. Sometimes, setup can be a lot of work.

-

-

Jeff Miller reeling out a transect tape

-

-

Laminated site reference photos help with the locating of pins and are used to confirm correct transect placement

-

-

Jeff Miller and Steph Topal secure in a transect tape on the terminal pin

While the setup team was hard at work searching for pins in a reef, the benthic monitoring team was following in their footsteps collecting data. With a team of three collecting data on coral disease, benthic composition, and coral health, they made quick work of a transect. To make things even more efficient, the team collects their data using iPads in underwater housings, which not only makes for easy data taking with the ability to easily integrate photos of disease but also allows for quick data entry – as all you have to do at that point is upload the info. While I spent most of my time at Bird Key with the setup team, I was able to join the monitoring team for a couple of dives and watch them at work. Watching them tear through a transect like it was nothing was pretty impressive.

Mike Feeley and Lee Richter making quick work of the transect

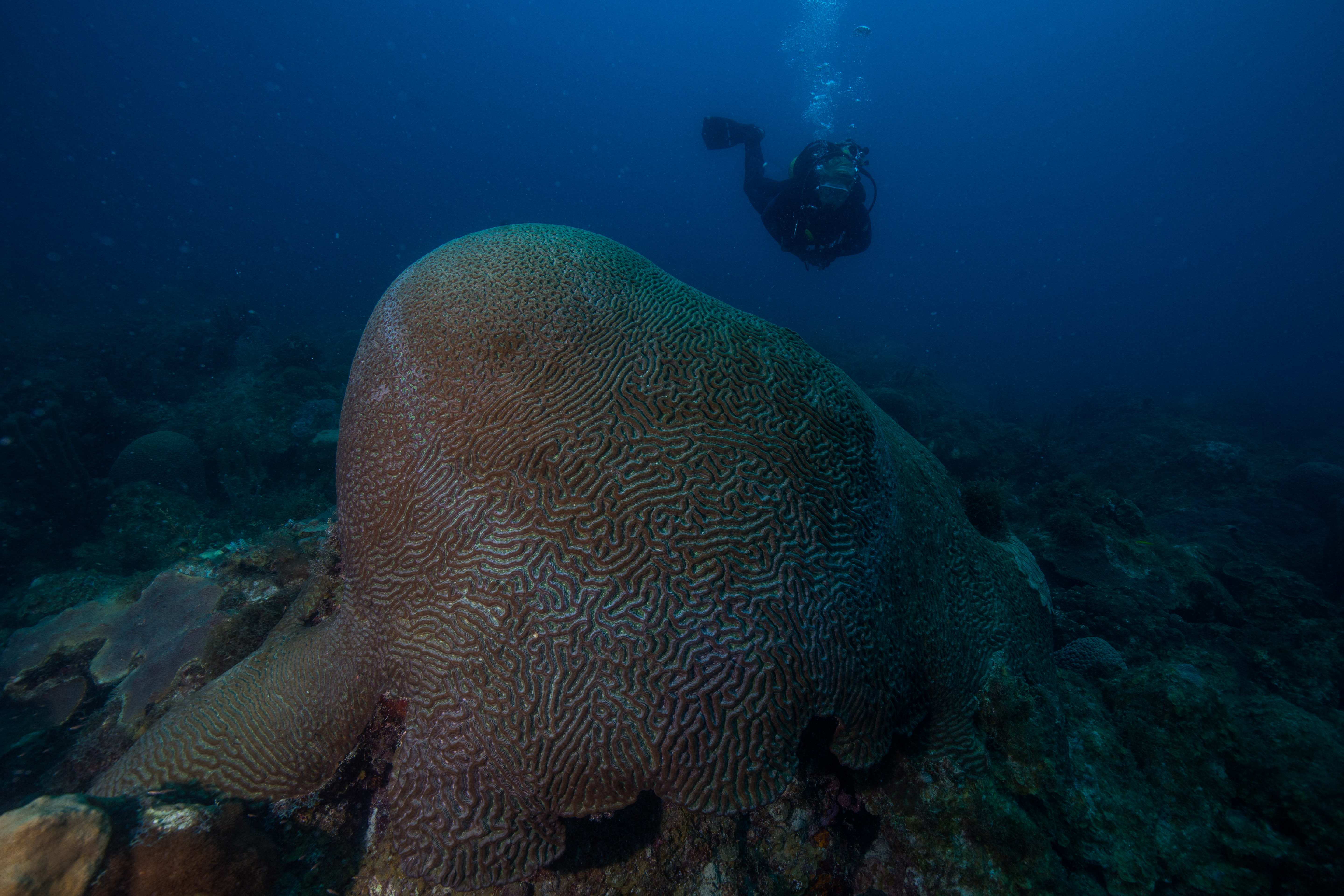

With a team this efficient, we made quick work of the Bird Key sites, finishing up in two days. Despite lower vis than other sites, Bird Key was a fun spot to dive. Lots of cool structure, one of the biggest coral colonies I’ve ever seen, and a huge and friendly resident goliath grouper that became accustomed to hanging out under our boat made for some pretty nice dives.

-

-

Now that’s a big fish

-

-

Huge Orbicella colony

-

-

Big fish (with Jeff Miller for scale)

The next couple of days we started working at a new reef, one named Santa’s Village (after the elf hat-shaped coral heads peppered around the site). Here, I worked with the setup team to find the pins and run transects as the monitoring team was diving on closed circuit rebreathers. These sites were much easier to setup than Bird Key, as instead of following a treasure map of transects we just had to find a center pin and then locate transects that were just 10m in cardinal directions from there. That made for a much easier setup, which gave us ample time to explore these sites. Beautiful reefs with pretty spectacular coral cover for the area, it was fun spending time to look around.

-

-

Morgan Wagner helps Jeff Miller secure a transect tape to a terminal pin

-

-

The survey team all geared up and ready to go (Left to right: Mike Feeley, Lee Richter, and Rob Waara)

-

-

Steph Topal works to set up a transect while the rest of the team observes

Here, our setup team consisted of the three interns (myself, Steph, and Morgan) and Jeff Miller. Jeff, who has been diving on these reefs for many years now, was a valuable resource to have around as he knew these spots like the back of his hand – he could tell you how that coral head was looking last year, or what makes that particular colony so unique. In our post-setup exploratory swims I stuck around his side and tried to soak up some of the information he had to offer. As someone with no previous experience in this area I had lots of questions for him, and highly appreciated being able to get such detailed and site-specific answers. However, these answers weren’t always happy ones. A rather typical post-dive discussion between Jeff and Mike would often be a somber reflectance of what it once was. The sites were visually striking in the volume of life present to an outsider like me, but a sad reminder of a steady decline for those who visit them once or twice a year. With this in mind, I tried to work with Jeff on the majority of our dives to document specific cases of disease, coral recovery or loss, or particularly healthy colonies – a nice way to put my photographic abilities to work.

-

-

Morgan Wagner observes a diseased coral colony

-

-

Unhealthy corals

-

-

Jeff Miller examines the remains of a formerly huge coral head

Returning to the M/V Fort Jefferson after a hard day at work

After a hard day at work monitoring, the team would offload gear from the SFCN’s Twin Vee to the M/V Ft. Jefferson, go through the prerequisite gear rinsing and decontaminating (due to the widespread coral disease in South Florida and the Caribbean, daily decontamination is becoming a pretty boilerplate process in most subtidal research operations) and start work on tank filling. This often left us a couple of hours free before time to begin dinner preparations – and what better to do than to get back in the water? Dry Tortugas was home to some pretty incredible snorkeling: the giant goliath groupers, baitfish and tarpon under the dock to the coral-encrusted fort walls themselves, to the patch reefs surrounding the islands. There was enough there to keep an underwater photographer busy for weeks. I took full advantage of all the free time I had, hopping back in the water with a mask, fins and camera almost every day of the trip.

-

-

A submerged portion of the moat wall off of Fort Jefferson

-

-

Sunset on the reef offshore of Loggerhead Key

Once we had polished up monitoring work at the Santa’s Village sites, we moved on to the final batch of baseline monitoring sites for the trip: ones at Loggerhead forest, a reef offshore of Loggerhead Key. These sites were set up in the same way as the ones at Santa’s Village with the easily located transect pins, which gave us lots more time to explore the sites and take them in. I found these sites at Loggerhead forest particularly beautiful, with some big and healthy-looking Orbicella and Colpophyllia colonies and lots of fish, but heard from the team that they’re now just a fraction of their former beauty. This illustrates the importance of baseline monitoring like this. Without knowing the past state, one could easily assume that the reefs are doing great with their high coral cover and fish density. When compared to previous years, the state of decline is more obviously clear.

As well as monitoring these sites, we worked on collecting and offloading temperature logger data. Over the years, the SFCN team has set out a large number of waterproof temperature loggers at various locations throughout the park to keep an eye on how things are changing. These loggers, which are located at all of the baseline monitoring sites as well as a collection of other select locations, must get their data offloaded occasionally to ensure they still have room to keep taking measurements. We did a good number of quick bounce dives (some required more searching for the logger than others) to offload data, which doubled as a great way to get a quick look at a wide variety of different sites.

-

-

Jeff Miller securing tempearture data from a logger

-

-

Divers search for a logger – some more difficult to find than others

-

-

Steph Topal and Jeff Miller work on offloading temperature data

Between all of the diving, snorkeling, photo processing, and sleeping that I was doing at this point in the trip, I really didn’t have too much time for much else. I was so preoccupied with that batch of activities (and they sure were nice ones to be preoccupied with) that it took me until about halfway through our time at DRTO to realize that some of the finest photographic opportunities this park has to offer occur after the sun goes down. Being located on an island that’s almost 70 miles away from the closest civilization makes for some pretty dark nights – which means that there’s some killer stargazing. Even more exciting to me was the discovery that the waters surrounding the fort are packed with bioluminescent organisms, creating an incredible glowing display when disturbed. These nighttime activities came to occupy my late evenings as I tried to capture all of their glory, keeping me busy each day after the sun went down.

-

-

Lightning storms off of Garden Key

-

-

Long exposure of bioluminescence around the Fort

-

-

Nightly celestial light show around Fort Jefferson

After all of the monitoring had been finished and the temperature logger data had been collected, we only had one last thing on our to-do list: some photogrammetry. While I’m now no stranger to photogrammetry after my time with the SRC up in Isle Royale National Park, I’ve never been involved with it being put to use on biological resources. After some careful work, it allows for the creation of a highly accurate model, which can be used to examine reef health and condition. The setup for this process was a little more involved than that of the monitoring. The areas that were picked to be mapped were both off of baseline transects in Loggerhead Forest, so the initial location wasn’t too hard to find as it was based off of previous transect pins. From there, however, we had to determine the location of the four corners of the survey zone in reference to those initial transect pins, and then to describe the locations of those corners with a heading and distance from the center pins and mark them with a slate to help with the processing. Once all that setup work had commenced, we were free to depart and let the photogrammetry team move in and capture all the necessary data by carefully swimming grid patterns over the site while continuously taking video, being sure to cover every inch of the allocated area.

Accuracy is crucial for tasks like this – the slightest deviation from the correct location could throw off the whole model. Here, Morgan Wagner and Jeff Miller double check their maps

And with that, all of the work we had planned was done – but our trip wasn’t yet. With a little more free time, I made sure to go check out the Fort Jefferson itself. I had been so occupied with all of the incredible in-water photographic opportunities that I had been neglecting the land-based ones. I spent the good part of an afternoon exploring the fort (and boy does it get hot inside a giant brick building in the afternoon sun) and taking all the photos I could.

Our final day in DRTO was occupied with diving. The plan was to do two recon dives to Sherwood Forest, the spot where the unique reefs of Dry Tortugas were first described. Estimated to be over 9000 years old and one of the best nursery habitats in the United States due to the highly complex structure, this particular reef is an incredibly valuable resource and could certainly use quick visual survey. Our dives on the site were paired with some current, which gave us a look at a good amount of the reef – I’ve never seen such a huge aggregate reef before. It seemed to stretch forever, and was even more incredible when considering the layers upon layers of old growth that are hidden under the uppermost visible part of the reef. Like the rest of the reefs in the Tortugas, this one no longer lives up to its former glory, but according to the experts on board our SFCN team it’s faring better than many others and still a sight to behold.

-

-

The never-ending reefs of Sherwood Forest

-

-

It’s wild to think about the many layers of coral hidden under the surface

-

-

With tons of places to hide out, this makes for a crucial shelter for vulnerable juvenile fishes

After returning from those dives, a subset of the team (Rob, Lee, and the interns) went back out on the water for a couple more fun dives. The first of those was a site called the Maze, a wildly fun reef full of complex structures like small canyons, swim throughs and small cave-like pockets under coral heads. I dove with Lee and had an incredibly memorable dive exploring these secluded little structures. Afterwards we ended the day with a classic DRTO wreck dive at the Windjammer, the wreck of an iron-hulled sailing vessel that sunk in the park in 1907. Structurally intact, fishy, and covered in healthy coral, this made for a great dive and a lovely way to end out our trip.

-

-

Lee Richter exploring cracks and crevices on the Maze

-

-

Steph Topal on the bow of the Windjammer

-

-

Divers on the stern of the Windjammer

Dry Tortugas National Park is a special place, and not one I’ll forget anytime soon. It has got so much going for it: a gigantic brick fort, island breeding grounds for hundreds of seabirds and turtles, beautiful seas and skies, killer snorkeling and diving, and a pretty phenomenal and biologically important reef system. All of these unique aspects packed into one Park and tucked away in the middle of the Gulf of Mexico make for a spot unlike any other, one of the coolest National Parks (and places) I’ve ever had the good fortune to visit. I’d like to extend a heavy gratitude to the SFCN team (Mike Feeley, Jeff Miller, Lee Richter, Rob Waara and their interns Steph Topal and Morgan Wagner) for having me along, making me feel welcome and allowing me to observe and partake in their work, as well as a big thanks to the crew of the M/V Fort Jefferson (Captain Tim, Mikey Kent and Brian Lariviere ) for taking great care of us during our time with them. I hope to be lucky enough to return some day, but for now I’m on to my next park of the internship: Biscayne National Park in South Florida.

Goodbye Dry Tortugas, you will be missed