The journey begins! The first destination for my internship is St. Croix, one of the U.S. Virgin Islands. I’ve never been to any of the Virgin Islands, so prior to leaving Colorado, I take some time to research the region and brief myself on its history. The largest of the four U.S. Virgin Islands, St. Croix measures in at 82 square miles. Reading this, I expect it to seem absolutely massive in comparison to the eight square mile island on which I lived in Thailand! Additionally, St. Croix is home to not one, but three national park sites: Buck Island Reef National Monument, Christianstead National Historic Site, and Salt River Bay National Historic Park and Ecological Preserve. On land, there are 18th century buildings scattered throughout the Christianstead waterfront, the oldest being Fort Christiansvaern, built in 1738. The five historical structures provide a glimpse into aspects of government on St. Croix during Danish sovereignty, from the colonial administration, to the international slave trade, to the military and naval establishments.

The historic buildings in downtown Christianstead offer a glimpse into St. Croix’s history and culture.

The Danish Customs House in downtown Christianstead

Underwater lies Buck Island Reef National Monument, the first designated Marine Protected Area (MPA) within the U.S. National Park Service. It wraps around two-thirds of St. Croix, and was dubbed by President Kennedy in 1961 as “one of the finest marine gardens in the Caribbean Sea”. Kennedy recognized the scientific, educational, and aesthetic importance of the area, and created the national monument in the hope of preserving its beauty and rich biodiversity for the benefit of the American people. Sadly, the reef has faced a number of challenges in recent decades. Invasive lionfish, hurricanes, disease, and coral bleaching events have all taken their toll. Currently, the biggest threat is Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD), a lethal coral disease that has been spreading rampantly throughout Caribbean reefs since 2014. I’ve come across the disease before (during my thesis fieldwork in Cozumel, Mexico), and I’m nervous to see the extent of the damage around St. Croix.

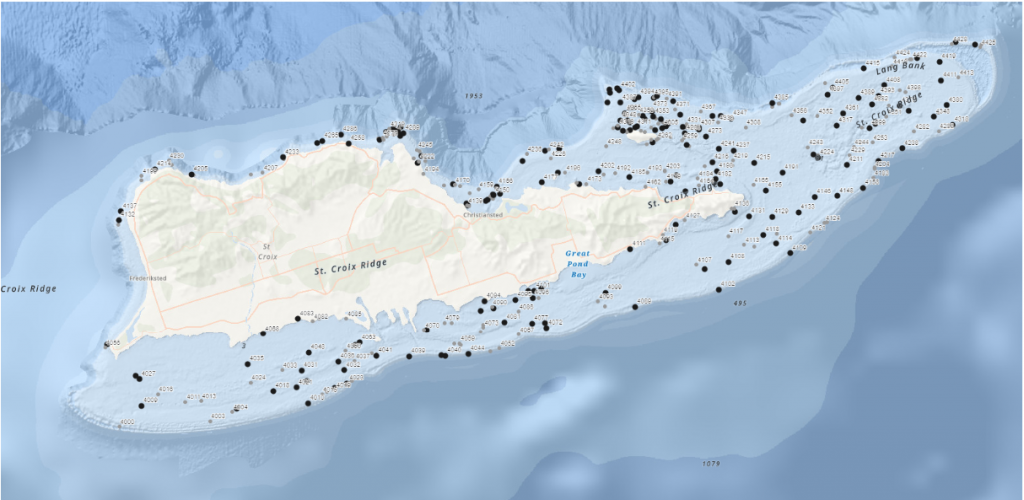

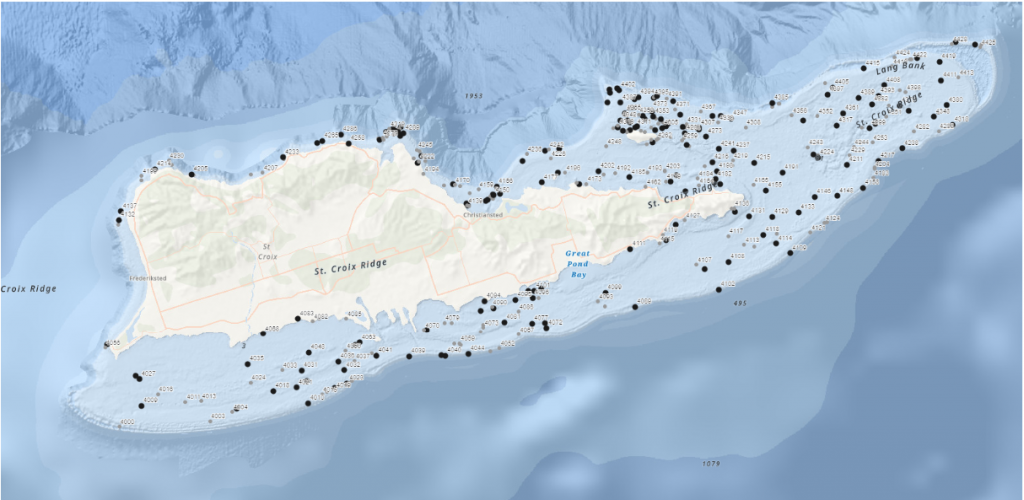

My two week assignment is to assist with the National Coral Reef Monitoring Program (NCRMP), a biannual survey that aims to assess ecological reef conditions such as fish species/composition/size, benthic cover (i.e. which substrates and organisms are present on the seafloor), and coral density/size/condition. Ultimately, the information gathered from NCRMP provides geographic and ecological context to inform and supplement local reef monitoring efforts, and aids general studies of tropical reef ecosystems. NCRMP covers a huge region, including Florida, Puerto Rico, USVI, and the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary off the coast of Galveston, Texas. The goal, for our current purposes, is to assess approximately 150 sites around St. Croix during the next two weeks. Typically, the NCRMP team surveys closer to 250 sites, but we’re working with a skeleton crew this year due to travel restrictions for NOAA personnel who are normally involved. Still, there are around 20 people working on the surveys this year, coming from a handful of different agencies: NPS, NOAA, the University of the Virgin Islands (UVI), the Nature Conservancy (TNC), and the Virgin Islands Department of Planning and Natural Resources (DPNR).

All of the sites to be surveyed around St. Croix and Buck Island are identified with a black dot. We will try to get to as many sites as possible in the next two weeks.

—–

It’s Saturday morning and I finish packing my bags, careful to weigh them so I don’t exceed the 50 pound limit per bag at the airport. I have a good feeling that the portable luggage scale I purchased is going to come in handy for the next few months. I try as best I can to cut the weight down, but I’m traveling for almost four months and need all my dive gear, running gear, underwater photography equipment, and of course, snacks. I end up with two 50 lb. bags to check and one carry-on that weighs around 25 lbs. Of course, I’m not thrilled by the thought of carrying my own bodyweight in luggage, but I reconcile my unease with the thoughts that I’ll be both extra-prepared and have stronger shoulders by the end of the trip!

I’ve had many people offer to “carry my luggage” for the duration of my internship. If only I could take someone up on it!

I have an overnight stay in Miami before my flight to St. Croix, and I’m incredibly thankful to have some help finding a place to crash for the night. Steve Barnett, the President of OWUSS, graciously connects me with Kenny Broad, an OWUSS scholar from the early 90’s. Kenny is now an accomplished cave diver, National Geographic Explorer, and professor with the University of Miami. He’s based in Miami and kindly offers me his guesthouse for the night, which I gladly accept.

I snagged the window seat on my flight to Miami and caught some gorgeous views.

After a restful night in glorious air conditioning (thanks again, Kenny!), I head back to Miami International Airport to catch my flight to St. Croix. I know that NPS Dive Officer Mike Feeley, my point-of-contact for this project, is on the same flight as me, so I send him a slightly anxious text before boarding. “Hey Mike, just in case I have bad phone service when I land at STX, I’m wearing a grey hoodie w/ black pants and a blue backpack. Will find you at baggage claim. See you in a bit!” Mike texts back with a description of his outfit, but I’ve already been told that he’s quite tall, which ends up being the easiest way to track him down once we land in St. Croix. His height and broad frame sticks out amongst the sea of travelers, and the NPS hat he’s sporting confirms my suspicions that he’s the guy I need to find. Mike is a good-natured, pop music loving fish biologist/ecologist with extensive experience working in the Caribbean. We chat in the airport while we wait for our bags, and are soon greeted by the rest of the NPS crew, Jeff Miller and Lee Richter. Jeff is a coral biologist/disease specialist who’s worked with NPS for decades. Initially, he seems fairly straight-faced, but I’m quick to learn that he has an endless bank of puns and dad jokes that make him and everyone around him chuckle throughout the day. He’s also an impressive athlete, and is the first known person to swim 23 miles unassisted around St. John (one of the smaller Virgin Islands). Similarly, NPS marine biotechnician Lee Richter is an avid athlete and outdoor enthusiast with a seemingly endless supply of energy. Mike, Jeff, and Lee all work for the NPS South Florida/Caribbean Inventory and Monitoring Network, so they’ve spent a lot of time with each other, both underwater and above. They catch up with each other in the car, and Lee and Jeff are more than happy to give me tips on where to run as soon as I express my hope to continue training for some upcoming endurance races after I’ve completed the internship.

The crew gives me a small tour of St. Croix, starting with the most important locale: the grocery store. (If you haven’t caught on, food plays something of an outsized role in my life.) Groceries are expensive here (welcome to island life), but they have most of the items you’d find in a grocery store stateside. We stock up on supplies and fill the bed of the truck with water, toilet paper, snacks, rotisserie chicken, and barbecue sauce (Jeff needs little more than chicken, barbecue sauce, and pita chips to fulfill his caloric needs). After the grocery store, we head to the condos we’ll be staying at. As we drive across the island, I remember my days on Koh Tao, and can’t help but compare the two islands in my mind. Koh Tao has roaming stray dogs, while St. Croix has free-ranging chickens everywhere. People drive on the left side of the road on both islands, but cars seem to be preferred over motorbikes here. As I continue to make mental note of the obvious differences, I feel an immediate, familiar calm to be back on “island time”. Once we arrive at the condos, I unpack my gear, chat with my roommate, and prep my dive bag for the next day. We’ll be diving first thing in the morning, and I can’t wait to jump in the water.

Dive gear and sustenance. What else do you need?

—

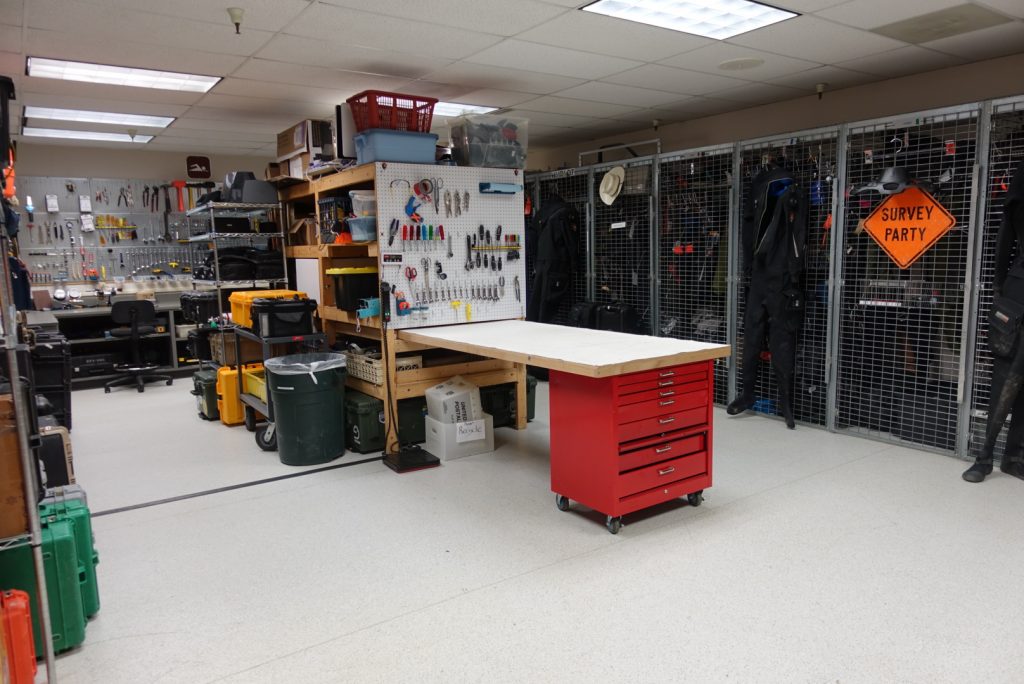

It’s Monday morning, the first day of NCRMP! Before heading out on the boats, the entire team meets for a project briefing at the NPS headquarters in town, located in part of the Christianstead National Historic Site, the Old Danish Customs House. The building was originally completed in the early 1840s, but underwent a complete restoration in 2010 after hurricane damage rendered it unusable. These days the first and second floors are dedicated to NPS park management. We all gather in the building and I eagerly meet more of the team. Most of the group consists of graduate students who are part of the Marine and Environmental Science program at the University of the Virgin Islands (UVI). They have a collective “quirky scientist” sense of humor that I love, but I embarrassingly can’t keep up with the banter. They’re obviously deeply knowledgeable about Caribbean corals and fish, and they throw around scientific names and references with such ease that it makes my head spin. Despite being a little overwhelmed, I’m thrilled to be surrounded by so many people who work in marine science—the atmosphere is filled with excitement and anticipation. We go over safety and logistical information, split off into three different boats, and start throwing gear in the trucks.

Jeff and Kristen start loading up Eddie Boy, our ride for the next two weeks.

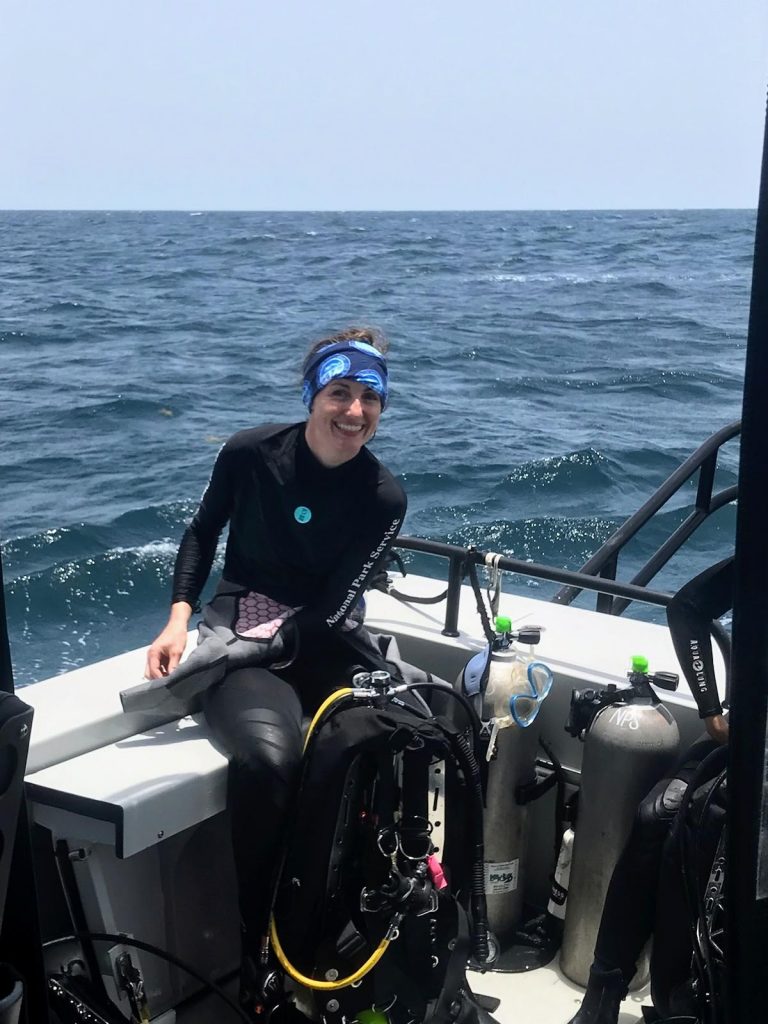

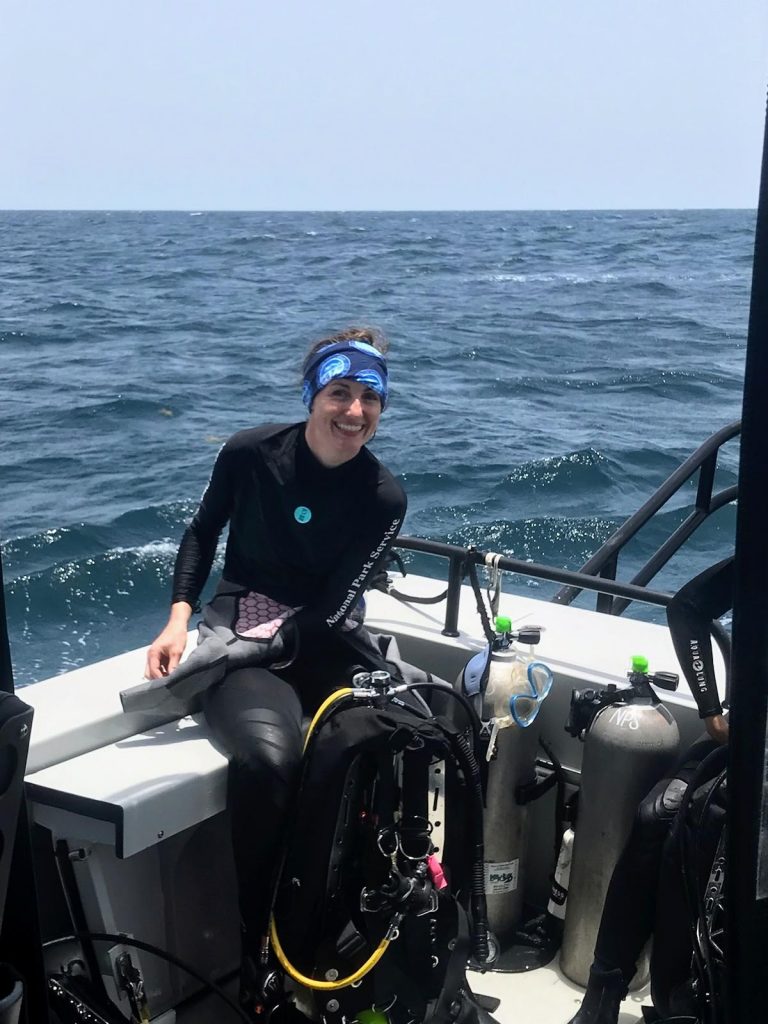

To my dismay, I’m told I have to stay out of the water because my dive-physical paperwork hasn’t yet been sent from the doctor’s office to the NPS. Trying to make the best of it, I plan to use the day topside as an opportunity to review survey protocols and study up on local fish and coral identification. I’m on the NPS boat, Eddie Boy, with Mike, Jeff, Alex Gutting, and Kristen Ewen. Alex and Kristen are both alumni from the graduate program at UVI, and continue to pursue coral reef research and fieldwork. Kristen is a Biological Science Technician and Dive Safety Officer for the St. Croix park, and shows a level of dedication to her work that I find quite impressive. She has wrangled rats (it’s a constant battle to keep them off of Buck Island), saved turtles, and helped rebuild coral nurseries around the island. Alex has also been pivotal in the island’s coral restoration efforts, and currently works for the Nature Conservatory as St. Croix’s Coral Conservation Coordinator. They’re both laid-back, proactive, and extremely knowledgeable about the local underwater ecosystem. I’m eager to learn from them and, more especially, to dive together.

Alex assembles her dive kit on the boat

After shuffling tanks and gear from truck to boat, our team takes off. The run to the first dive site goes quickly, but I soon notice things going wrong. A headache develops. My stomach starts to turn. I’m incapable of taking my eyes off the horizon without the feeling of nausea. The familiar, yet dreaded, feeling of seasickness begins to set in.

I’ve dealt with seasickness before, but normally it subsides as soon as I jump in the water and head underwater. Today, however, I’m stuck on the boat for the day, and I have no other option but to fight it topside. Ultimately, I lose the battle. For the next few hours, I alternate between leaning overboard to provide food to the fishes, and laying in a corner of the boat deck with my eyes closed, listening to the rest of the crew jump in and out of the water. Thankfully, everyone is sympathetic. I feel significantly better once we get back to land. We spend the drive home exchanging war stories. In an attempt to mitigate my self-consciousness, Jeff tells a story about another intern. “This poor intern,” he starts, “we pick her up on her first day and take her to this local restaurant, great spot we think, and we all have dinner. The next day the food poisoning kicks in and we have to take turns jumping off the boat and swimming downstream for a few minutes to get everything out between dives. Just terrible.” I take a moment to appreciate the fact that I only had to deal with vomiting, and not other forms of GI distress. We stop at the store to stock up on Dramamine, and I cross my fingers for a more successful day tomorrow.

My favorite spot on the boat for the first two days of the project.

To my dismay, Tuesday isn’t much better. The waters around St. Croix are normally choppy, but even the most seasoned divers are getting sick today. Eight-foot swells knock the boat back and forth all day long. I manage to make it in for the first dive, but even with a healthy dose of the anti-seasickness pills, I’m not able to keep it together for the whole day. Back to the floor of the boat for me.

The first two days are mentally challenging. Seasickness isn’t something you can just will away, even when you try your hardest. Once your inner ear starts disagreeing with your eyesight, the brain reacts with a burst of stress hormones, and suddenly you’re incapacitated—physiologically convinced that you’re in the spin cycle of a washing machine. I find it especially difficult to deal with seasickness when other people around me don’t have it. In this case, it makes sense that I am the sole victim, seeing as I haven’t been on a boat in the last year, while my crewmates spend many of their workdays out at sea. Despite knowing this, it’s tough to spend the first two days of the internship I’ve anticipated for over a year feeling absolutely awful and, to that end, incapable of diving or helping the crew. Is this how it’s going to be all summer? Am I not cut out for this? Anxious thoughts preoccupy my mind for much of Tuesday. I’m supposed to be working and contributing, not sitting on the sidelines. I worry that my crewmates are starting to question my abilities as much as I’m questioning myself. Desperately hoping to get past this, I try to draw from my ultrarunning experience and focus on problem-solving. What can I control? How can I fix this, going forward?

On Wednesday, I’m determined to avoid getting seasick. I take one Dramamine in the morning (apparently three is overkill and makes things worse, as I learned yesterday), followed by a larger breakfast than usual. I bring lots of food and water for the boat, and I learn that the weather is supposed to be better today. At long last, I get to experience a full day of diving on St. Croix. Finally! We celebrate my revival and a day of calmer weather, and Mike begins to lead me through training.

By the middle of the week, I’m up and about on the boat (and MUCH happier) thanks to the wonders of Dramamine.

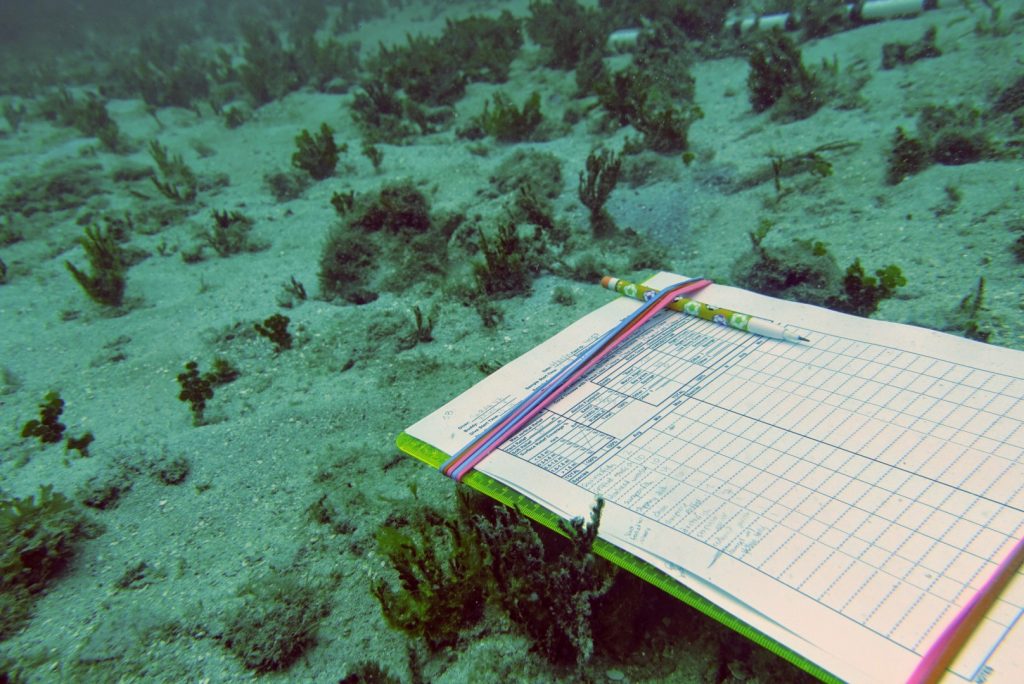

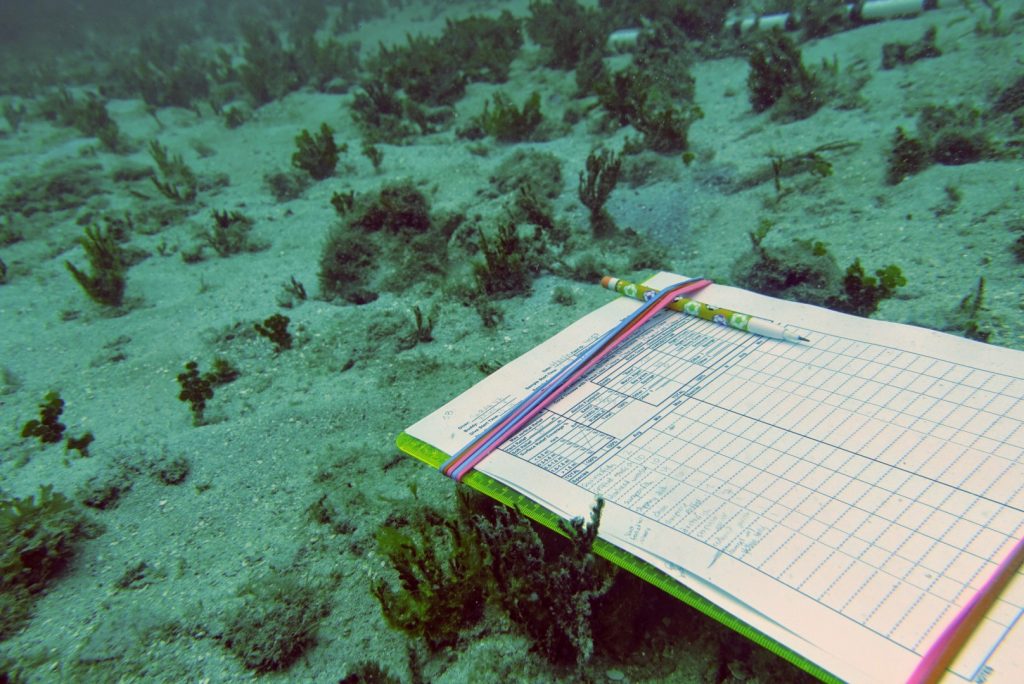

NCRMP surveys are focused on two main types of data collection: fish surveys and benthic surveys. There are two people per team, and both assessments are required at most sites. One person stays on the surface to drive the boat, and the other four divers drop down to conduct the surveys. I’ll be doing fish surveys for the whole project, which involves recording all the fish species seen at a site. We take note of fish counts and sizes first. Next, we do a quick environmental assessment, which provides details on the type of site and the condition (anything from sand patches with dominant seagrass cover to aggregate reefs with healthy corals). Meanwhile, the benthic team assesses coral cover on the seafloor by laying out a transect tape and documenting which coral, algae, or seagrass species are touching the tape. These surveys typically take about 25-35 minutes, so there’s a lot of jumping in and out of the water all day. On a good day, we can hit six or seven sites.

The crew: Kristen (left) and Kaya (right), both sporting their underwater themed leggings.

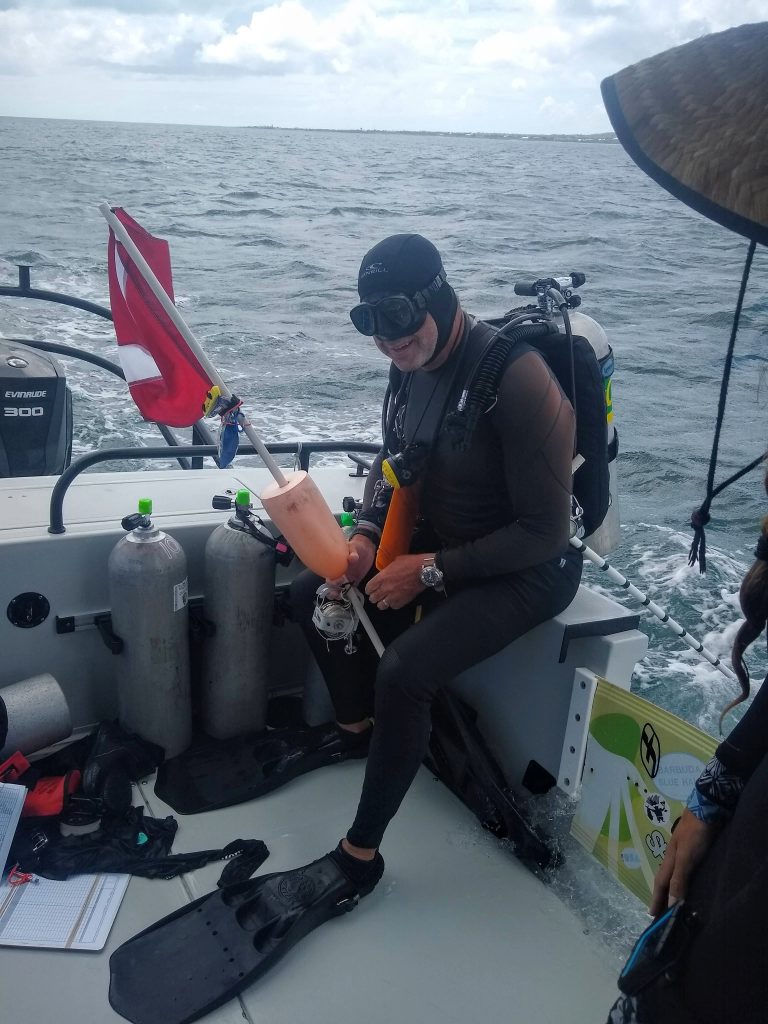

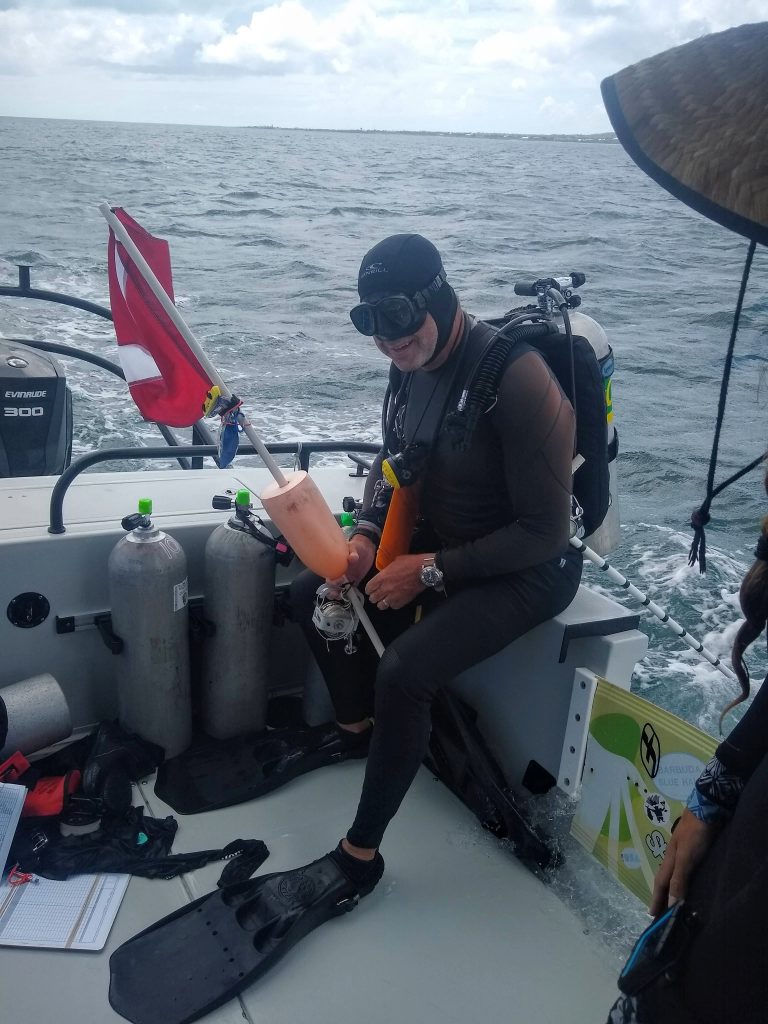

Jeff, ready to jump in.

Mike awaits the go ahead from Kristen to jump in. The dive flag buoy gets tied down underwater and helps the boat driver locate the team when they finish a dive.

It takes me a few dives to get used to the routine. Despite having watched everyone on the boat execute dives and discuss protocols for the first two days, I’m anxious about correctly executing the dive as I buckle the straps of my fins and sit on the side of the boat, ready to back roll off when we are on site. Because we need to survey specific coordinates for each dive site, everyone has to be ready to roll into the water as soon as the boat hits its GPS waypoint and the driver says, “Go divers, go”. There’s no lingering at the surface, as the current can quickly take you away from the designated site. Instead, we do a negative descent, an entry technique that involves squeezing all the air out of our BC before we jump in so that we start sinking as soon as we hit the water. I haven’t done this sort of entry much in the past, so it’s jarring to jump overboard and begin free falling through the water within seconds. I notice my heart rate shoot up during the first few descents, but I’m thankful for the opportunity to practice the entry method. Once we fall to the seafloor my heart rate calms, and I am back in my element.

Kristen catches me in the middle of a survey as I record fish numbers and sizes. The red and white fish in the photo are squirrelfish. (photo credit: Kristen Ewen)

Essential data collection equipment – clipboard, data sheet, and a pencil.

By Thursday, I’m elated that I haven’t experienced any further seasickness. Finally, I begin to feel like I’m hitting my stride. The crew is settling into a rhythm as well, and we all seem to have ways to boost morale and keep the collective energy up. Mike is the DJ of the boat (I push for 70’s rock, but today’s top hits win out) and Jeff provides clever puns and one-liners throughout the day. I bring along chips, gummy bears, or cookies to share every day. “Ah, the health food aisle,” Mike jokes when he finds me in the junk food section of the grocery store as we make our daily stop on the way to the marina. We have a long day, so snacks are crucial. Our sites are on the other side of the island, so we have to nearly circumnavigate the whole of the island. The run to the first site takes an hour and a half, but it’s a great chance to see the less populated and more wild areas. When I see the unpopulated Jurassic Park-esque green cliffs on the south side of the island, I wonder what it must’ve been like to discover the island in its original state, untouched by people.

One of the UVI boats cruises back to shore at the end of a workday.

Untouched green cliffs on the south side of the island.

The day is going smoothly until Jeff notices that the dual engines aren’t moving in unison when he steers. I scan over the engines and realize that, to our collective panic, the steering system has broken. I’m able to grab the bolts that broke off before the ocean sweeps them away, and Jeff and Mike manage to fit one bolt back into place. It’s enough of a temporary fix for us to get back to the marina, but we have to cut our dive day short.

Mike works on a temporary fix for the boat’s steering system.

On Friday, Jeff has made dozens of calls to try and get Eddie Boy fixed, but a mechanic can’t look at it until mid-afternoon. Luckily, the NPS has another boat in the marina that we can use for the day. Kestrel is a small boat, with a firm “three points of contact” rule when it’s moving. It also has less cover, so most of us don our wetsuits pretty early in the day, as being doused with saltwater on the way to the first dive site is a given. It’s a beautiful day for diving until mid-afternoon, when a storm rolls in and gives us a heck of a return ride. I’m amazed that one pill in the morning can make eight-foot swells and churning waves somewhat fun—the joys of modern medicine! By the end of the day, however, and after a week full of unexpected ups and downs, the crew is ready for the weekend. Personally, I’m excited to catch up on writing, go trail running on the east end of the island, and to spend some time with the rest of the team I’ve yet to hang out with.

I love the bright greens and blues of the island and its surrounding waters.

My new favorite hat, and one last run at home before a summer of travel!

My new favorite hat, and one last run at home before a summer of travel!